With the death of Sonny Myers on Monday, May 7, 2007, at age 83, the world is short one less genuine character. Whether it was making a headlining wrestling career out of a 200-pound frame and then becoming perhaps the world’s slowest referee, working as sheriff in Buchanan County, Mo., or the Sonny Myers Carnival, Myers went to his own beat.

His 60 years in pro wrestling are intrinsically tied to St. Joseph, Missouri. One of St. Joe’s latter-day wrestling graduates, Ed Wiskoski (Colonel DeBeers, Mega Mararishi), can rhyme off tale after tale.

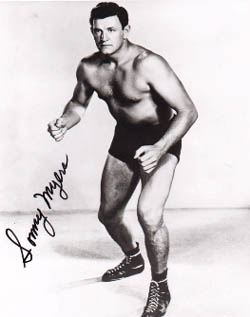

Sonny Myers

Sonny Myers? “There was a bandito from the word go. I’ve got a thousand, million stories on him,” claimed Wiskoski, who grew up knowing of the legend, and then got to spend time around Myers. “You talk to the old guys that were in the business with him, and he was just a con artist. He’d go into a restaurant, and he’d sit down with a guy that was sitting there all by himself. He’d order his dinner and start bullshitting with him. Then he’d get up. He would say to the guy sitting at the table, he’d say, ‘that gal up there taking the money, she fancies you.’ ‘What do you mean?’ ‘Well, I drop in here quite often. She likes you.’ Myers would go up with his ticket and he’d lay it down. He’d say, this guy at the table I’m at, he’s got my ticket. Of course, the gal would wave back at him and point at the ticket that he’s going to pick up. Myers is out the door and gone. But that’s just one of the things the guy used to do.”

Stan Holek, who worked as Stan Nielsen and Stan Lisowski, got to know Myers on a trip to Japan in 1960. “He was a character,” said Holek, a real fun guy to have along on a trip. “They’d take us to these hot houses, hot baths and things. Sonny, he said, ‘I’ve never seen so many that don’t got chests — they look like ironing boards!’ I just had to laugh. He was a character. He could make you laugh.”

Mad Dog Vachon said that he was often asked if he knew Sonny Myers, but he didn’t meet him until Sonny was old and refereeing in Kansas City. Vachon later saw tapes of Myers and knew why they asked; “He was so handsome. That’s why so many women asked me, ‘Where’s Sonny Myers?’ They loved him, he was such a nice looking man.” Wrestling Revue once plugged Myers as “college-bred, smooth and handsome as porcelain.”

Dick Brown, the son of another Midwest great, Orville Brown and a wrestler himself, started to laugh just hearing the name Sonny Myers. “I can’t think of anybody who did more with less of a body than Sonny Myers. They used to call him Bag Of Bones. He got over very well in St. Joe, and he did in other places too. He really was a junior heavyweight, and should have been a junior heavyweight probably. He had some very good matches.”

So while on the one side, Myers was a true original, marching to his own drummer, in the ring, he had few peers.

“He was fantastic,” simply stated Wiskoski. “He was a really good worker.” Former referee Tommy Fooshee echoed the comment: “He was fantastic. I saw him in his prime.”

“In my opinion, Sonny was probably the best pure all around worker I’ve ever seen,” Jody Hamilton (The Assassin), told the Georgia Wrestling History web site.

“Sonny was probably the best of the best when it came to the clean side of wrestling,” Harley Race said in the St. Joseph News-Press following Myers’ death.

Born in 1924, Harold C. “Sonny” Myers grew up on a Savannah, Mo., farm. While employed on the killing floor of Swift’s packinghouse, Myers met St. Joseph wrestling promoter Gust Karras in 1943 at the local YMCA. The 6-foot-2 Myers had been playing basketball.

“One night I was up there, and I just happened to walk in room where the boys were working out, and I didn’t even know they were working out. I walked in there and said, ‘Jesus Christ, let me out of here!'” he told this writer in April 2006. “Gust Karras looked at me, and he laughed. He used to smoke a pipe all the time, and, boy, he started puffing on that pipe, and I said, ‘My God, how does anybody get a breath in here?’ He said, ‘They do. Pretty soon, you’ll never know it. Once you get in a building where you’ve got three, four, five thousand people, everybody’s smoking, you don’t pay any attention to it. And he was right.”

Having gotten his parents’ permission to train, Myers was soon on the way to a professional career. But wrestling was hardly the only sport that he excelled at. Myers spent two years at the University of Missouri, where he wrestled and played baseball. During the summers, Myers was a semi-pro baseball player as well. “I loved all sports, all sports I loved, and I did good at all of them. It’s just because I liked it. You’ve got to like something if you’re going to do something good,” he said.

Sonny Myers as Mr. Texas

“The Missouri Meteor” carved out an incredible in-ring career. He was a 14-time Central States champion, the NWA Missouri champ, a five-time champ in Texas, and held tag belts with Dizzy Davis, Pat O’Connor, Leo Garibaldi, Larry Chene and Bobby Graham. In the 1960s, Myers teamed with Johnny Weaver in the Ohio-Indiana territory as the Weaver Brothers, feuding with the Nielsens and Angelo Poffo & Bronko Lubich.

“I wrestled and had so many belts so much that you forget,” Myers admitted.

Forgotten by history and circumstance — and devious promoting, perhaps — was Myers’ brief run as a recognized world champion. He defeated Orville Brown in November 1947 for the version of the belt. However, in early 1948, the National Wrestling Alliance was formed, and recognized Brown as its first champion, leaving Myers’ reign confined to the history books.

His legacy lived on through a lawsuit, however. Myers sued P. L. (Pinkie) George, Des Moines promoter, and the National Wrestling Alliance for $600,000 in an anti-trust action in the 1960s. Myers’ contention was that the alliance and George had a monopoly on wrestling and caused him financial damage. The feud with George dated back to 1953.

The lawsuit was successful. “He collected ninety thousand dollars from them and they had to sign an agreement that they wouldn’t continue the monopoly. He nailed them,” Lou Thesz said in an interview in Whatever Happened To … in 1999. “Pinky George did a stupid thing. He said, ‘I’ll see that you never wrestle anywhere again.’ That’s it — bingo! After that, they all had to sign a consent decree that they would not be involved in any restraint of trade.”

“One of the handsomest physiques ever carried over the coaxial cable. Anyone who has seen him in action can testify to his superb cat-like agility as he maneuvers to apply his favorite holds: the Atomic Drop and the Japanese Sleeper,” promoted Wrestling Revue.

His favorite place to wrestle? “I’ll tell you the truth, the best wrestling I ever had and made money was, I was booked out of Houston, Texas. That was Morris Sigel and the guy that booked the territory for him was [Doc Sarpolis].” It was also in Texas where he was stabbed, and wound required 248 stitches to his belly.

Wrestling took Sonny and his wife, Elaine — whom he met at the matches, and married in 1947 — all over the world: England, France, Germany, Mexico, Canada, Alaska, Australia, Japan seven times. But he couldn’t shake his St. Joe roots. “I used to love to come home,” he said. He and Elaine raised two sons, Steve and Michael.

Aside from wrestling, the Sonny Myers Carnival ran for 22 years, meshing a show that his brother-in-law had with his own. “We took our two shows, and put them together and made a big one. We just did oodles of money,” Myers said. “Back in those days, it was 25, 30, 35 cents for a ride. You put them people on them rides, and give them a nice ride, they’ll come back and keep riding. A lot of people will put them in there, and put them on a 25 or 30 cent ride, and put them on the ride and when they start out, you can count the circles that the damn ride makes before they stop it. That’s no good, you can’t do that.” When Myers was on the road, his sons and his wife ran the carnival.

He also owned three local farms that used to provide beans and corn, but that had recently been converted to tree farms. “Shit, we’ve made more money out of them than anything else,” Myers said, explaining that he had more than 6,000 trees on about 150 acres. In later years, Myers also worked at a car dealership, and at a Wal-Mart as a greeter.

Myers also served two terms as Buchanan County sheriff in the 1970s. His years as a self-promoter served him well, said Wiskoski. “He knew how to work the press.”

Like his wrestling career, Myers’ years as a public servant bring out stories as well. The one told the most, perhaps, is his bust of a long-tolerated illegal cock fighting game in southern Buchanan County. “I went there one time. You couldn’t even see the building until you were right up next to it. It had black tar paper around it. But inside it, it was all bright lights and everything else,” said Wiskoski.

Myers decided to go after the illegal cock fighting and get some publicity; he and his deputies busted it, and arrested 35 people. “The magistrate court was overflowing Monday morning,” Bob Slater, former St. Joseph News-Press managing editor said in the obituary. “Sonny was not one of the good ole boys.”

The dead roosters went into storage. “By the time it was all said and done, and about a year’s worth of trial, all the county ended up getting out of it was a big bill for the cold storage of the dead cocks,” laughed Wiskoski. “He ended up with egg on his face there.”

As a wrestler, Myers competed off and on up until about 1980, at which time he helped out here and there as a referee in the Central States territory based out of Kansas City, and would be brought into other territories as a special NWA troubleshooting referee. (Having had both knees replaced, Myers was not exactly known for flying across the ring as a ref.)

He also trained wrestlers — using the gym at Lord Littlebrook’s St. Joe home — and promoted the occasional show. Myers figured he had 15-20 people come through his door asking to be trained. Myers shared a tale of his own: “When I put the squeeze on them, they say, ‘Hell, what are you trying to do, kill us?’ ‘No, I’m not trying to kill you. I’m trying to make things so that you can win.’ He said, ‘I ain’t never heard anything like that.’ ‘Well, then you ain’t very smart then.'”

Myers died on Monday, May 7, 2007, following a two-month illness. Funeral arrangements are not known at this time.