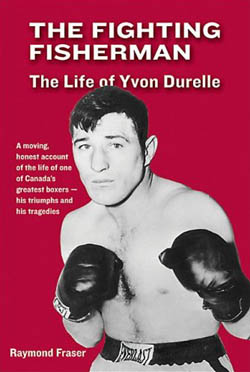

While “The Fighting Fisherman” Yvon Durelle is justly celebrated in the boxing community as a true Canadian legend after his death Saturday, January 6, 2007, at age 77, it’s worth mentioning that he parlayed that fame into a 15-year off-and-on wrestling career as well.

A former British Empire boxing champion Durelle, was a celebrated figure in Atlantic Canada. Born October 14, 1929 in the small New Brunswick fishing village of Baie-Ste-Anne, one of 14 children, Durelle faced a hard road in life, and found boxing as a good outlet.

Challenger Yvon Durelle, right, scores with a punch in fourth round of a light heavyweight title bout with champion Archie Moore at the Forum in Montreal in this Dec. 10, 1958 photo.

His early years as a boxer — he turned pro in 1948 — were spent fighting around the Maritimes, and by 1953, he was Canadian Middleweight champion. A short while after dropping that belt, he would move up in weight class and capture the Canadian Light-heavyweight title on numerous occasions.

But it was his World light-heavyweight championship fight against champion Archie Moore on December 10, 1958, at the Forum in Montreal, that gave him a near-cult following — even though he lost the bout in the 11th round. [Moore would later be president of the ring-based Cauliflower Alley Club.] Durelle was listed as a 4-1 underdog, and it was one of the first fights broadcast coast to coast on American television. Durelle stunned boxing patrons by knocking the champion down three times in the first round. Under boxing rules today — except those of the World Boxing Council — the fight would have been stopped after three knockdowns in one round and Durelle would have been world champion. He also missed an opportunity when, after the first knockdown, he stood over Moore watching for several seconds before returning to his corner. As a result of his delay, the referee had to wait to begin the count, and Moore made it to his feet at the count of nine. Durelle swarmed all over the champion for four more rounds and knocked him down again in Round 5. But Moore held on and eventually wore Durelle down to retain his world championship with an 11th-round knockout.

Durelle would retire from boxing in 1963 with a 90-24-2 record, with 51 knockouts. His other well-known bouts were two with future heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson in 1954. One of Durelle’s last major fights would be an attempt to win the Canadian heavyweight title in 1960, but a young George Chuvalo would stop his bid in the 12th round.

That fame would naturally attract the attention of wrestling promoters. Durelle served as a special referee for many bouts before ever becoming a grappler himself. One of his early sparring partners was Joe Kayorie, who would go on to moderate fame as professional wrestler “Killer” Joe Christie.

“A wrestler named Joe Christie helped me too. He couldn’t go that far but he’d do a couple of rounds a day,” Durelle recalled in Raymond Fraser’s 1981 biography The Fighting Fisherman. “I wasn’t too hard on him because he was old, eh? I didn’t pay him either. But there were some guys not so good.”

In a conversation in July 2006 with SLAM! Wrestling, Durelle tried his best to recall some of his wrestling moments, but had great difficulty.

“A lot of things I don’t remember,” Durelle said. “Boxing and wrestling, I wrestled a long time, a long time.”

Wrestling was a sideline, a hobby almost. “I boxed harder than that [wrestling]. It was tougher.”

Al Zinck has been involved with the Maritime wrestling scene for decades. Durelle wrestled and refereed for Zinck’s International Wrestling promotion in the 1970s.

“He was a rugged fisherman,” Zinck recalled of Durelle. “He was just a fair wrestler, that was all,” able to work maybe 15 minutes. But “he was a draw.”

According to Fraser, it was Montreal promoter Eddie Quinn who first convinced Durelle to become a pro wrestler on the side, with early purses as much as $500 a night. “But then Quinn took sick and retired and Yvon was forced to freelance, traveling to places like Belleville, North Bay, Kapuskasing, Sudbury, Temiskaming … and without Quinn’s patronage (Yvon says he treated him ‘like a son’) he was paid much less,” wrote Fraser. “He soon got homesick and returned to Baie Ste Anne and for the next decade wrestled on and off in the Maritimes for Cowboy Len Hughes, where a peak night on the mat would earn him one hundred dollars. For a period wrestling was practically his sole source of income, that and a bit of fishing.”

Zinck vividly remembers Durelle knocking out Stan Stasiak’s two front teeth in Bridgewater, Nova Scotia when he didn’t pull a punch. Durelle couldn’t recall that incident. “Could have been, could have happened,” he said.

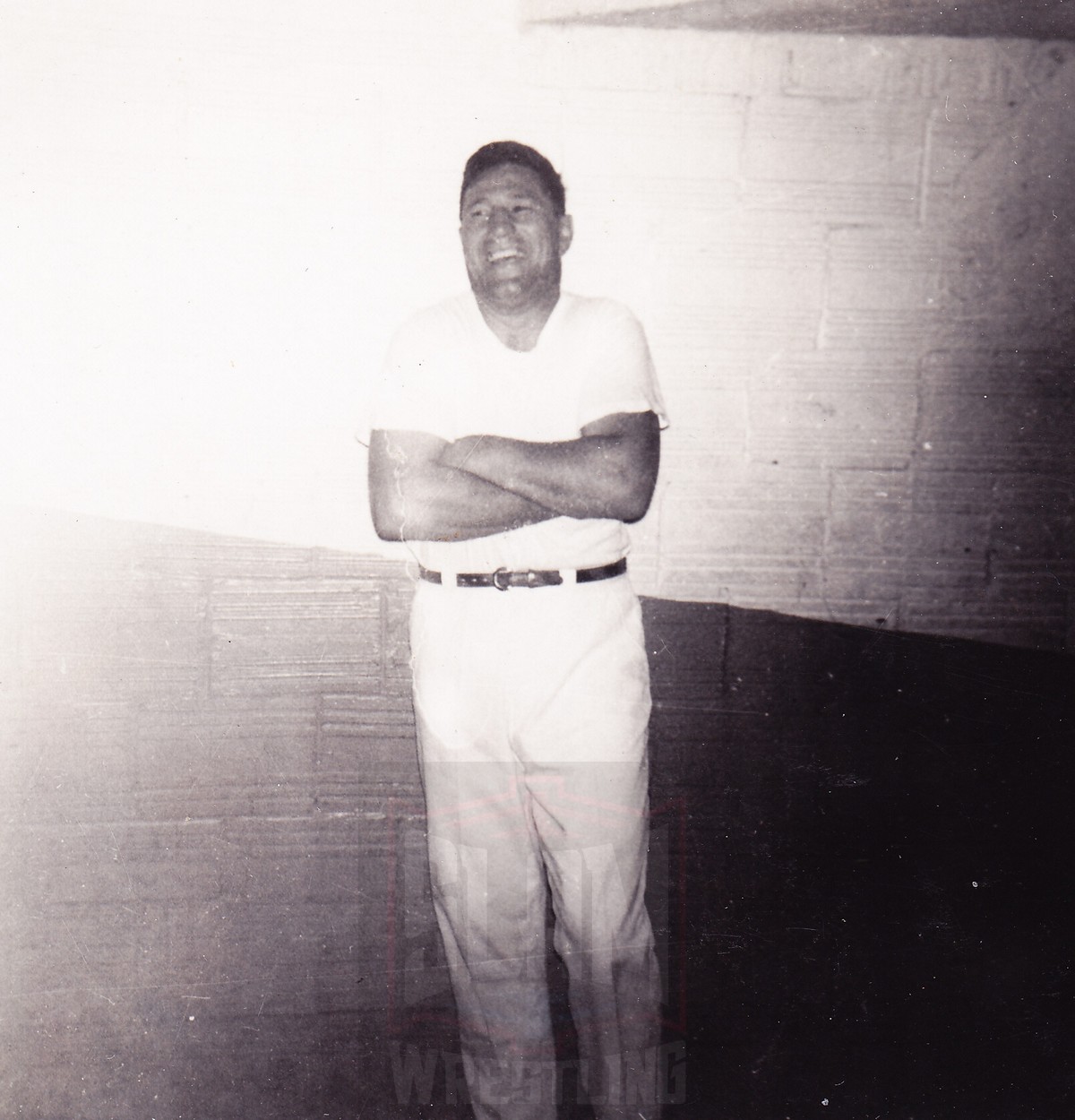

“The Fighting Fisherman” Yvon Durell in Halifax, circa 1963. Photo by Boxer/wrestler Vvon Durelle. Photo by Melanie Wilson

There was never any question of which side Durelle was on; he was the local hero, though the skills of the 205-pound boxer-turned wrestler may not have been polished.

“I was a good guy. It was a lot of fun. I enjoyed it,” said Durelle. An old clipping from a Halifax wrestling show promotes Durelle as a headliner against Count Bruga, advertising him as the “Former Canadian and British Empire Lightheavyweight Boxing Champion.”

Fraser detailed more of Durelle in the ring in his book. “He was supposed to be, in the black and white world of the grunt game, a ‘good guy,’ but as he puts it, he was more what you’d call a ‘bad good guy. I used to bite, punch, pull hair, everything, because the people liked it. They wanted me to win but they liked me to be bad when I was doing it. I put on a great show with the Stomper … I packed the Halifax Forum with Bulldog Brower. The people would go crazy. Old Bull Currie, when I fought him in Chatham there was a riot. He cut my head with a chair and I broke a bottle and went after him and he jumped out of the ring and run away. The wrestlers were nice fellows, but some tried to throw their weight around … I clipped a few guys … I straightened them out. Sure, you knew who was going to win before the match, but it could get pretty rough in there just the same. But I never knock wrestling, it was good to me, and I had fun.'”

An Yvon Durelle autograph. Greg Oliver collection

Bill Donovan, a sportswriter for the Saint John Telegraph-Journal, used to referee bouts. In The Fighting Fisherman, he talked about Durelle as a grappler. “Yvon enjoyed himself wrestling,” Donovan said. “He didn’t need such good conditioning, he could rest between holds, which he did quite often. He was funny to watch, he’d try these complicated holds … I had to bite my tongue to keep from laughing. The villains used to break up at him. But after a whole he got too ‘smart,’ playing too much to the house. But he was funny, he knew how to electrify a crowd. Some of the guys got mad at Yvon when he was first in the business because he didn’t know how to pull back the punches. But it was the same with any new wrestler. Yvon would ding his opponent by mistake and the guy would get mad-but then he’d remember who he was in against, and he didn’t stay mad. Durelle was always trying to get his opponents laughing, he’d tickle them and make really outrageous remarks-you know the kind of thing, two guys tangled up on the floor. It was a great lark to him. He took a ‘bad bump,’ as they call it in the game, up in Ontario, in Brockville. He wasn’t able to catch himself, the reflexes just weren’t there. He landed on his head outside the ring and suffered a concussion and shoulder separation and was in the hospital for a while.”

That fall in Brockville saw Durelle tumble to the floor, through the top and middle ropes. In a magazine article on Durelle, Larry Kasaboski, the promoter for the show and much of Northern Ontario, recalled what he saw. “After a few seconds Yvon tried to get up. It was pathetic to watch. His eyes rolled back in his head and he slumped in my arms. I was certain he was dead. We left him right there and a doctor was called. Knowing that he had done so much boxing I feared he’d never come out of it.” Yet Durelle was back wrestling a month later.

“He got hurt different ways than he did boxing. His elbows were all crushed, like you took a hammer and smashed them. He’d come home and his back would be covered with scratches,” Durelle’s wife Thérèse said in The Fighting Fisherman. “And he used to have to drive so far. From Friday to Monday he’d be gone, he’d drive all the way to the far end of Nova Scotia and be back at six or seven o’clock Monday morning in time to go to work. If he had fifty dollars to show for it he was be doing good.”

Durelle has said he thought he could make money in the ring, but when he retired in 1960, he was broke. After trying a number of jobs, he opened a nightclub, The Fighting Fishermen, in 1975.

Two years later, Durelle became involved in a dispute with a customer and ended up fatally shooting the man. He was charged with murder but his lawyer, Frank McKenna, who would later become premier of New Brunswick, successfully argued self-defence. After the shooting, Durelle closed the club and retired.

His biographer Fraser remembered Durelle as charismatic and a self-proclaimed comedian. “From a distance, I thought he was a frightening man, which he would be to an adversary in the ring,” said Fraser. “But really when you get to know him, he’s a very good-natured, good-humoured man with a lot of presence. He loved to tell stories, loved to talk about himself and laugh at the things he’s been through.”

Durelle is a member of the New Brunswick Sports Hall of Fame, the Canadian Sports Hall of Fame, and Canada’s Boxing Hall of Fame. In 2003, Ginette Pellerin of the National Film Board of Canada made a French documentary on his life called Durelle.

Robert Richard, who runs a website about Durelle, said the boxer was not only a Canadian sports hero, but also a hero for New Brunswick’s Acadian community.

“He made his mark internationally, and he reached levels that were never seen before by a sports figure in the Acadian culture,” Richard, 42, said from Robertville, N. B.”He was the greatest hero of modern time for the Acadians.”

Richard said he wasn’t much of a boxing fan until he ended up in Baie-Ste-Anne for a funeral more than seven years ago.

His father was a big fan of Durelle’s, so he decided to pay the former boxer a visit. “I spent about two or three hours in the house, they invited me in and I didn’t expect that,” Richard said. “I was brought into Durelle’s museum, into the kitchen to have a cup of tea and we talked about his life and his career. They greeted me so warmly.”

After the meeting, Richard started to collect memorabilia, films and photographs related to Durelle’s life. In the years since, Richard has kept in touch with Durelle and his wife.

Durelle suffered a stroke on Christmas Day and also had Parkinson’s disease. He died in a Moncton hospital on Saturday, January 6, 2007.

— with files from Canoe wire services