OTTAWA — Ten years. That’s how long it has taken Dangerboy Derek Wylde to get to this point in his wrestling career.

Drenched in sweat, beneath the lights of Ottawa’s Scotiabank place, Wylde (real name Dennis Stewart) is catching his breath after a rigorous work out in front of World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) representatives.

He was the first to volunteer to get in the ring for a brief wrestling match, along side fellow Ontario indy grappler, TJ Harley. It was a chance to show what they can do in the ring.

Dangerboy Derek Wylde (left) and TJ Harley rest up after their match at the recent WWE try-out held in Ottawa. Photo by Corey David Lacroix

“I’ve been waiting for this for a long time,” said Wylde to SLAM! Wrestling. “I volunteered first because I’m confident in my abilities. Why sit around waiting?”

It’s the must-have attitude if you want to make it to WWE. That and the physical conditioning to endure the demands that comes with the live-action spectacle of professional wrestling.

For those who attended the try out in the nation’s capital, it was a chance to see if they have what it takes. Some, like Wylde, are active wrestlers. He and Harley knew what was coming and it showed when it came to handling the grueling regime of Hindu squats and running the stairs.

“I’m having a wicked time,” said Harley (real name Mike Holt), now in his seventh year as a professional wrestler. “It’s a lot of fun and I’m all smiles because this is freakin’ awesome. I’m on cloud 10, maybe even 11. I’ve had some of my best matches with Dangerboy. Me and him have been hurting each other for a couple of years now. I was just happy to get in the ring with him here. It’s probably one of my greatest moments up to this date.”

“We’re both personal trainers at the same gym,” Wylde added. “It’s funny that we ended up in the ring together because we’ve pushing each other every day to do more and more. He would tell me to do 500 squats in a row and I would get mad, in a good way, and do 600. I would then make him do 700.”

The fact that both athletes are at this try out is a testament to their love for the business. Wylde in particular can probably tell you of the countless faces he’s seen come and go on the indy circuit. Many gave up, unwilling to continue the hardships of brutalizing your body for little or no pay.

Then there are those who passed Wylde by, going forward to work in the big leagues, the same place he wants to be.

“I keep going for this,” Wylde says, motioning towards the ring where his fellow candidates take their turn in the ring. Draped on the perimeter of the ring is a banner that reads Smackdown, the weekly television show watch by millions of fans across the continent. “It’s the love of wrestling. Even if I never make it, I’ll still keep going for as long as my body will hold up.”

But being a competent wrestler is not enough. Nor is it enough to have that Herculean physique that has become the hallmark of the WWE product. Remember, this is sports entertainment.

“I’ve been very lucky that when I do independents (wrestling shows), they give me a lot of mic time,” said Cody Deaner, another Ontario based grappler who was also in attendance at the try out. “It’s a big part of wrestling, obviously. We’re entertainers, apart from being athletes.”

In real life, his name is Chris Gray and he’s been here before. In fact, he actually had the chance to wrestle at a live, televised WWE event in November of 2004. So, what happened?

“I was complimented on my wrestling abilities, but I didn’t get the call. They weren’t saying you’re good enough to get a contract,” Deaner told.

It was a crossroads of sorts for him. Back then, his ring persona was Cody Steele, a youthful looking, blond-haired grappler with a toned physique. The type of look that would draw approving squeals from young girls in attendance.

But it wasn’t what WWE was looking for. “Every time I come to do try outs, I keep asking people, ‘What do I got to do? Give me advice. What do I have to work on to get a contract?'” Deaner said.

The answer was be different. For in the world of sports entertainment, having something that stands out, that certain magnetism that connects with fans subliminally is what can make you stand out from everyone else. And if you stand out, you are an attraction and that makes money.

With that revelation, Deaner set out to do just that.

“I’m not the biggest guy in the word, so I can’t show them that I’m a big monster,” Deaner said. “I decided to do something that stands out. I cut my hair, grew a mustache and changed the whole gimmick.”

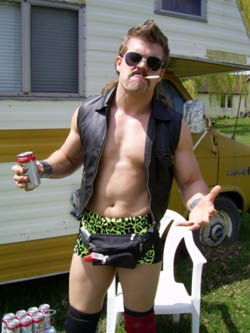

Add in a mullet to that description and Cody Steele became Cody Deaner; the poster child for unemployed, trailer park white trash everywhere. Inspired from the Canadian cult hit film Fubar, it’s a blatant stereotype, but it works. The gimmick has become a cult phenomenon of sorts among indy wrestling fans, his antics riling fans wherever he appears. Yes, he’s different and he’s getting more attention because of it.

Cody Deaner. Being different can get you noticed.

“I Americanized it a little bit, a southern twang, so they understand a little better when I’m in the States. It’s just something I’ve done to stand out and be different.”

In making the change, Deaner showed initiative in learning as much as he can about the business and a willingness to adapt. It’s a proven attitude to have if you really want to be successful.

Just ask WWE star Ken Kennedy.

“I knocked on the door for about six and a half years,” told Kennedy (real name Ken Anderson).

It was at the end of the try out session that Kennedy made an appearance at ringside. Looking at the cluster of hungry faces brought back many a memory for Kennedy of his days on the indy wrestling circuit, chasing the same dream he’s now fulfilling.

“Every time I would come to these try outs I would bust my ass. I was so hungry.”

Hunger, obsession, devotion; call it what you will, but it was that inner strength that drove Kennedy to work hard at his chosen vocation. In hearing Kennedy tell of his rise to success, he draws a clear map for aspiring wrestlers everywhere on what it takes to get where he is now.

“I remember wrestling a match in Milwaukee and I went up to a guy who I kinda looked up to at that time and I asked him ‘Do you think I could send a tape to WWE (then WWF) and do you think they would take a look at it?'”

“He said ‘No, you’re not ready. I wouldn’t send anything because you don’t want to make a bad first impression.’ To me, that was bullshit because if I go there and they tell me I’m the shits, then a year from now, when I send another tape, and I know I’ve improved, they’ll see that improvement and they’ll say ‘Hey, this guy can learn and we can teach him.’ After I asked the guy and he told me not to, I went home and made a tape.”

He sent that tape and that bold step paid off when he got a call from former WWE commentary and talent scout, Kevin Kelly. It would be the beginning of a long process of nurturing a relationship with the company.

“They brought me down to a couple of shows as an extra. Didn’t do anything, just sat around, but I knew I was sort of in the door,” said Kennedy. “If I saw that Raw or Smackdown show was coming to Milwaukee, Chicago, Cleveland or anything within a thousand miles of my home I would drive. WWE pays the extras a little cash, so it was enough to cover my expenses. In fact, I would have done it out of my own pocket and I did many times.”

It’s called sacrifice and it’s a huge barrier to many a wannabe wrestler. Kennedy has met his fair share of people who just don’t have the will to make sacrifices, who just don’t have the hunger he has. Professional wrestling is not something you can do half-ass; you have to want it because it’s who you are.

“Guys come up to me all the time and say ‘Hey, should I be a wrestler?’ and I say ‘No’. Nobody ever had to tell me, I never had to ask anybody. Lots of people told me not to after I told them that I was going to and I said ‘Go pound sand, I’m going to do it,'” said Kennedy.

What Kennedy did was to absorb as much information as possible on how he could improve as a performer. As much of a physical art form that wrestling is, it is also cerebral. Knowledge of the endless intricacies of a match and how to bring an audience into the choreographed drama being displayed is mastered by few.

As Kennedy told during a past conversation with Kelly, paying your dues on the independent wrestling circuit is where the most important lessons are learned.

“One of the things Kevin Kelly told me was ‘I don’t care if you’re wrestling in front of five people and you’re working the shittiest guy in the world, you’re going to learn something in that match. Have as many matches as you can and get as many matches under your belt and always try to learn something from every match.’ I still do that today.”

The uncountable number of matches, the hints from experienced trainers, the networking with WWE; it all paid off when Kennedy had his try-out with the company and got his deal with Ohio Valley Wrestling (OVW), a talent development promotion based in Kentucky.

Ken Kennedy

“Eventually I got to the point where I was confident and I knew what they were looking for,” said Kennedy. “I had a try out similar to this situation right here and there were a lot of people there. I was the only who knew what they were looking for. I went in there and I was hungry and aggressive.”

It’s a good bet that those who attended the try outs in Ottawa will not get the call. Even so, Kennedy made it clear that those who aspire to be in WWE must continue to network with the company as much as they can.

“It’s like any other business, you have to network,” he said. “You can’t wait for someone to knock on your door. You have to go to them (WWE) and show them that you want it.”

“I see that stuff all the time. Guys will come to a try-out, they don’t get asked to come back and they don’t want to swallow their pride and make the phone call and say ‘Hey, can I come back?’ They’re like ‘Well, they know me now. If they (WWE) want me, they can call me.’ Well, don’t hold your breath.”

Making it to the big time doesn’t mean you’re on easy street. As history has shown, anyone is susceptible to being released from their contract at anytime. Again, keeping a pulse on what others think about your performance may just help you avoid that unpleasant scenario.

In Kennedy’s case, he goes right to the owner of WWE, Vince McMahon. “Every time I come back from a match, I look at the boss and say ‘Vince how was that?’ Some days he’ll give me the thumbs up, other days he’ll ream my ass out. I don’t want to be stagnant. I want to go to the top.”

They all want that, but the fact is, only the select few will.

With that bitter fact in mind, perhaps the most important lesson one can learn is make sure you have back up plan if you don’t make it to the WWE.

“I got my four-year degree in English language literature and last year I just finished teacher’s college,” said Deaner.

He’s holding back on starting a career in teaching. Just another sacrifice when it comes to chasing a dream. “I want to concentrate on this. Wrestling isn’t a hobby for me. This is what I want to do for a living.”