By MARK DOW

In 1944, when he was 15, my father went to a war bonds fundraiser at Houston’s City Auditorium with his father. The evening featured a match between world champion Wild Bill Longson and Lou Thesz, “The Scientific Wrestler,” followed by music from the Houston Symphony Orchestra. My dad says he remembers that University of Oklahoma wrestler Ellis Bashara — still sweating profusely and bleeding from a cut on his head — conducted the orchestra, and that the harpist fainted. A bit odd, but apparently not far from the truth: as violinist Irving Wadler remembers it, Bashara didn’t conduct, but he did attack the conductor when the orchestra broke into Chopin’s Funeral March to signal Bashara’s demise at the hands of George Wagner, later to become the Human Orchid, a.k.a.Gorgeous George.

Almost 30 years later, as a pre-teen, I caught the stinging end of a Mexican bullwhip in the balls. It was my whip, brown and white braided leather, a gift from a Mexican-American friend, and one of my brothers was at the other end. I think my brother was surprised that he had been able to crack the thing at all. Of course it hurt like hell. When I ask myself which of my four brothers was at the other end of that bullwhip, one layer of memory shifts just enough to be visible beneath another. I remember that my older brother whipped me. That makes sense, since David was the one who could whip me. And I would whip Steven, the next younger one, and on down through Stuart and Leon. That was the idea. But in the haze I think I see Steven at the other end. That would probably explain his surprise: the fluke was not just that he had summoned the wrist-action to crack the whip, but that he had hurt his older brother. So on top of my physical pain was outrage because the system had been violated. And the outrage was to mask my humiliation that my little brother had hurt me. I’m almost sure that once I pinned my older brother on the sidewalk across the street from our house and even successfully banged his head against the concrete once or twice, but he denied it so often and so authoritatively that eventually I doubted myself, and now I have no idea if that victory was a fantasy.

The Mexican bullwhip made sense to us because we were experts at rat-tail fighting. A rat-tail is a rolled-up bath towel wielded as a whip. If you can make the tail snap, you can hurt somebody. A lot of people know that a rat-tail is more dangerous if the tip is wet. But most people I knew who used rat-tails did not understand the importance of preparation. The guys in the locker room at school would roll up a towel by holding one corner in each hand and flipping the thing round and round its own axis. Some of them, especially the jocks, accustomed to depending on brute force, didn’t even use two hands. They would hold the towel by one corner and, as it hung down, just twirl it around as if they were making a ribbon dance. My older brother taught me this: lay the towel flat, bring one top corner down to the midpoint of the bottom edge, repeat with the other corner, and roll it up along one of the new diagonals, evenly and tightly. The thicker end is your handle. Wet the tapered end and you can raise welts. I don’t know where David learned to do this, but I always felt it was something only we, my brothers and I, did, something only we understood.

One afternoon I was fighting Alan S., my friend and my equal, in his front yard. We were in the fifth or sixth grade together at Beth Yeshurun Day School, and we lived on the same block of Glenmeadow in Houston. I don’t know what we were fighting about. We might not have been fighting about anything, just wrestling. My older brother was over on the sidewalk, shouting encouragement to me. At least that’s what we later agreed he had been doing. Alan’s father, a big fat man with ears that stuck out — we called him “monkey ears” behind his back — came out to the front step. He accused my brother of telling me how to fight. In disgust, he extended his right arm and pointed down the street. “Go home,” he said. “Just go home.” Mr. S. was a fraud, though we didn’t know that yet. He sold insurance, and he was purportedly a Bible scholar. On Friday evenings we sometimes went to his house along with a few friends from the neighborhood to read and discuss the parsha, or Torah portion, of the week. Mr. S.’s framed insurance credentials were on the walls.Years later, my father assisted Mrs. S. in divorce proceedings, and he found out that the scholar had fabricated the credentials.

Like many adults, Mr. S. couldn’t always tell whether, in our terminology, we were “play-fighting” or “real-fighting.” Neither could our own parents, though they did understand that one often led to the other. The difference, we believed, was clear, and that may be one reason we were both fascinated by and contemptuous of professional wrestling. Houston Wrestling was televised live on Saturday nights and repeated on Sunday mornings. Sometimes we would watch both broadcasts. My father didn’t mind that we watched, but he would never have thought to take us to a match (he didn’t mention the war bonds event until very recently), and we probably would never have thought to ask. To us, Houston Wrestling was a television show.

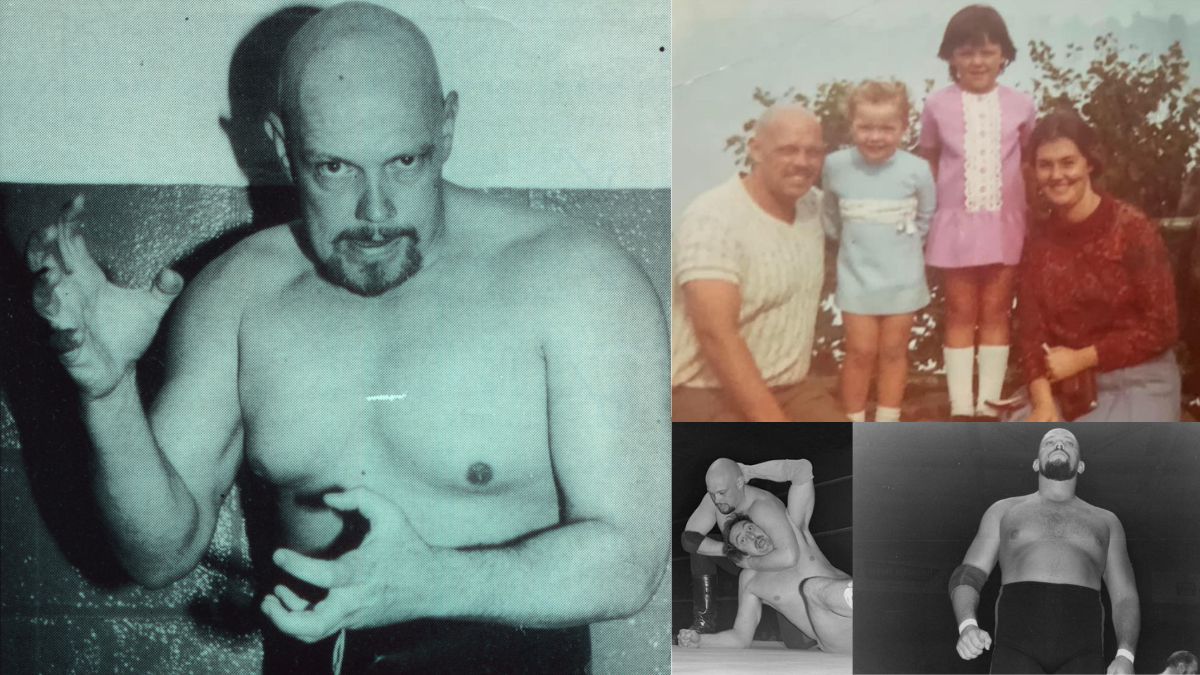

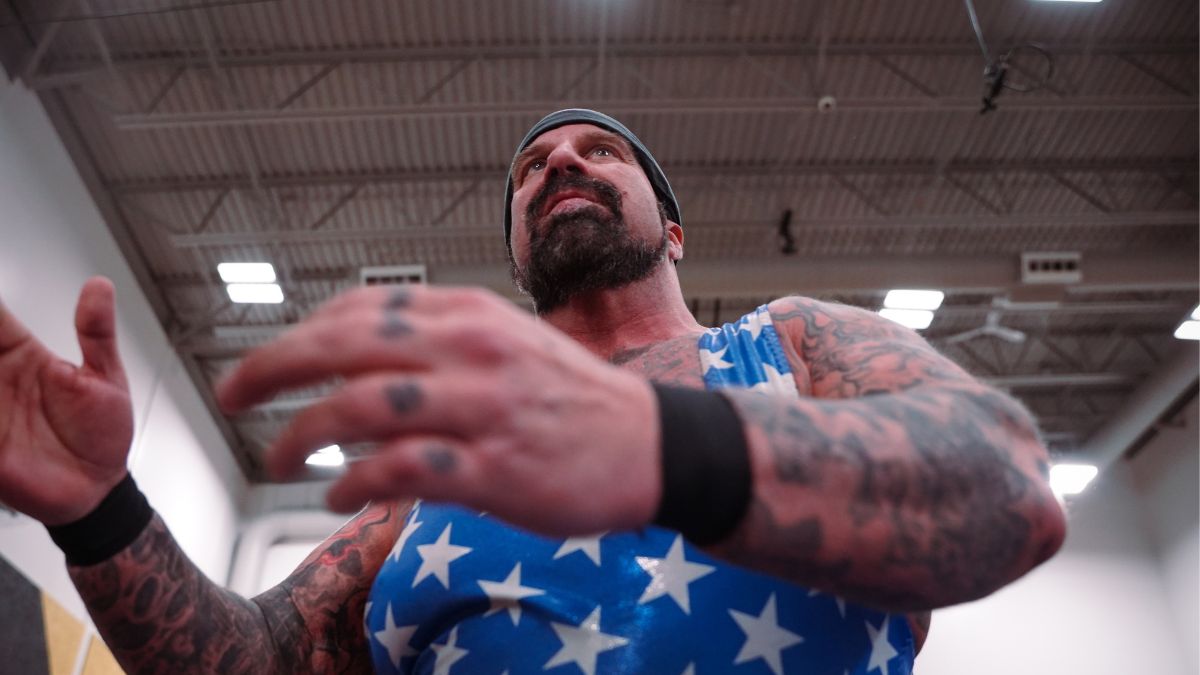

Around the time of the Mexican bullwhip incident, Bubba Walters invited my older brother and me to the Sam Houston Coliseum. Bubba was our friend Craig’s father. They lived down the block, in the opposite direction from Alan, on our side of the street. At the Coliseum, we bought a black-and-white glossy of the our favorite tag-team, a pair of clean-cut brothers named Nick and Jerry Kozak. I don’t know which bouts we saw, but we didn’t see any of the more spectacular wrestlers: Wahoo McDaniel, who wore a feather headdress and skirt and devastated opponents with his Tomahawk Chop; Mil Mascaras, the Mexican wearing a mask that covered his entire head, who would dive from the top turnbuckle onto his prone opponent; or the exotic and acrobatic Argentina Apollo, always maneuvering to get his opponent between his legs in the dreaded scissors lock.

Our friendship with Craig faded in the controversial aftermath of our trip to the Coliseum. My brother and I declared that Houston Wrestling was fake. Not only did Craig and Bubba disagree, they were insulted since they had taken us to a match. Of course we were thrilled to have gone, and would continue watching — we had believed it was fake before seeing it in person. Bubba’s defense of the obviously staged event was especially puzzling to us since he had been a real featherweight boxer when he was young; we’d seen the framed pictures from his fighting days. So I wrote a letter about our disagreement to Houston Wrestling host and promoter Paul Boesch, who responded: Your friend is right. And added: If you think it’s fake, why do you watch? All on a postcard.

Maybe I should have told Paul Boesch how much we learned from his show: full-nelson, half-nelson, hammer lock, arm bar. Applying these holds came naturally because we had an instinctive knowledge for soft spots and pressure points. It simply made sense to slug someone over and over again as hard as you could in the side of the upper thigh to give him a charlie horse — and to yell “Charlie Horse!” as you did it. Or to announce “Trapezius!” as you clamped fingers into another’s trapezius muscle, or “Stomach Claw!” while digging into the tender points on either side of the abdomen. The most vicious of the claws, and perhaps the only hold whose name had to be shortened as it was applied, was Fritz von Erich’s Iron Claw: hand over your opponent’s forehead, fingers and thumb into the temples. My older brother was the only one with sufficient hand strength to apply the Iron Claw consistently and effectively. “Japanese Finger Lock” might also seem too long a name to announce as you apply it, but it took a few seconds of positioning. Place the palm of your hand over the back of your opponent’s hand, right to right or left to left. With your fingers extending slightly beyond his, push his fingers into a fist, and then continue to press his fingertips in, as if you’re trying to make them bend between the first knuckle and the fingertip.

Then there was the hold we called “Mano la Puerta.” The name would mean something like “Hand, the Door.” You simply push the opponent’s hand forward so that the wrist bends farther than it’s built to. A Mexican friend in Miami, however, assures me that the phrase “Mano la Puerta” is meaningless. It turns out we were giving each other the “Mano de Puerco,” or pig’s foot, something the Mexican police might do to you; it’s what prison guards in the United States call the “gooseneck.” A third hand hold, the “Lee-ata Bendable,” was a simple matter of bending the fingers backwards. We gave it that name out of playful acceptance of our youngest brother Leon, since it was one of the few that he could apply.

But sometimes there wasn’t time for playfulness. One day at school, Alan sneaked up behind me and stole the kickball as we walked back to class from recess. Alan was quick and coordinated, the fastest runner in the class. In the final issue of our sixth grade newspaper, he revealed that his goal in life was to win the Olympic speed skating championship on hockey blades; the rest of us had no idea what he was talking about. When he stole the ball, I went after him, pinned him to the floor in the auditorium, and banged his head several times against the linoleum while sitting on his chest. When little Miss Elterman asked me why I did it, especially since Alan was my friend, I told her that he had hit my hand when he stole the ball. That was a lie, of course. The truth was that I didn’t really understand the question.

When I tried to spray hairspray in Steven’s eyes, I did it for a reason. I tried to explain that reason to my mother as we stood in the hallway outside Steven’s room, where he had managed to escape and slam the door. She seemed more frightened and shocked than angry. I had told Steven that if he didn’t do something, or stop doing something, then I would spray hairspray in his eyes. If I didn’t make good on the threat, he wouldn’t take me seriously. I remember how David once stood in that same narrow hallway all our rooms opened onto, looked our father in the eye, and explained things more simply. “They obey me,” he said.

Copyright Mark Dow 2006. All rights reserved.

RELATED LINK

Mark Dow now lives in Brooklyn. He and his brother David R. Dow are co-editors of Machinery of Death: The Reality of America’s Death Penalty Regime. He can be emailed at mdow@igc.org.