Oh, to be young, carefree, living in sunny southern California … and publicizing professional wrestling.

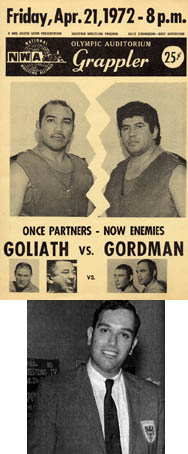

Jeff Walton, lower photo, and one of his programs.

Well, it’s not exactly the stereotypical beach bum lifestyle, but to Jeff Walton, it was just as much fun.

“I’m kind of the fan who ended up getting into the business,” Walton told SLAM! Wrestling from his California home. “It’s not your typical career path, but I really enjoyed it.”

He’s hoping others will enjoy it just as much. Walton’s book, Richmond 9-5171, A Wrestling Story, is chock full of tales from his years of experience as a fan, publicist, promoter, announcer, and manager, mostly in southern California.

Despite the urgings of son Scott, Walton initially balked at putting his reminiscences on paper. After all, he reasoned, he was not a big-name wrestler or top industry mogul.

But talks with his friends and family convinced him that a treasure trove of memories from what was one of the wrestling capitals of the world would be greeted warmly.

“I said, ‘I think I’m going to do it because there’s a lot of fans on the East Coast and other places who might get a chuckle out of these stories.’ It was actually almost a two-year process getting it all together,” he said.

“Wrestling fans want to know what the inside scoop is. I don’t think I would have done it 10 or 15 years ago, but the business is not protected any more and you’re not hurting anyone.”

A fan as a kid, Walton’s first one-on-one exposure to the business came after he and a friend heard wrestling star Freddie Blassie offhandedly mention on television in 1962 that he was traveling to Denver.

They dutifully drove to the airport, stood in the terminal, and awaited the appearance of the “Hollywood Fashion Plate.” Far from the vile, flesh-gnarling villain he portrayed in the ring, Blassie was genuinely pleased by the attention.

Walton then started a fan club for Blassie, and kept Blassie’s name in circulation after a kidney operation knocked him from wrestling superstar to car salesman. Blassie never forgot the favour, and, when he returned to wrestling in 1967, told Walton: “Thank you, you kept my name alive.”

“He was larger than life,” Walton said of Blassie, who died last June. “He really was not a great worker, but he was a great showman.”

In his youth, Walton also wrote for wrestling magazines – an early piece was on a wrestling school run by the same Mae Young who “flashed” Chris Jericho on WWE Raw recently.

In May 1969, he hooked on with the Los Angeles territory, publicizing shows at the famed Olympic Auditorium and the rest of Mike LeBell’s southern California circuit for $250 a week.

Over time, his role as publicity director expanded to the point that he was promoting shows in nearby El Monte and co-producing the live Saturday night television show that drove crowds to the house cards.

While it sounds like a wrestling fan’s dream, Walton remembers that the positions came with their share of headaches.

“The publicity man is always the man in the middle because he has to be accountable to the matchmaker or the promoter and also be able to help the wrestler’s career. So you were serving two or three masters,” he said. “But I think everybody I met in the business, I enjoyed being with.”

After the California territory disappeared in the early 1980s, Walton took a stab at managing, becoming the wicked, bleached-blond Tux Newman in the Jerry Jarrett/Jerry Lawler Tennessee promotion.

There, he hooked up with a young Randy Savage, among others, before growing weary of the long road trips, low payoffs, and time away from home.

He also worked briefly on the publication that would become WWF Magazine. But he left the industry when WWE owner Vince McMahon insisted that he relocate from California near the company’s Connecticut headquarters.

Today, Walton, 57, is a civilian supervisor with the Santa Monica Police Department. He follows today’s version of wrestling as a sports entertainment from a distance, but still maintains friendships and contact from his days with Blassie, LeBell, and others.

And he’s astounded to see that four-page programs he wrote and designed as a young man often sell for big dollars at internet auctions. “I can’t believe some of the prices those old things get,” he said. “But it’s nice to know there’s still a certain nostalgia for that time.”

RELATED LINK

- Review: New L.A. book full of anecdotes