If you tune into a Senior PGA golf tournament, only to find Fuzzy Zoeller lodged headfirst in a sand trap, or Lee Trevino pleading for mercy in a tee box, there’s a perfectly logical explanation. “The Living Legend” is on the course.

Larry Zbyszko, star wrestler, announcer, and agent provocateur for some of the most memorable angles in wrestling history, now has his sights set squarely on the Senior PGA tour, renamed the Champions Tour last year.

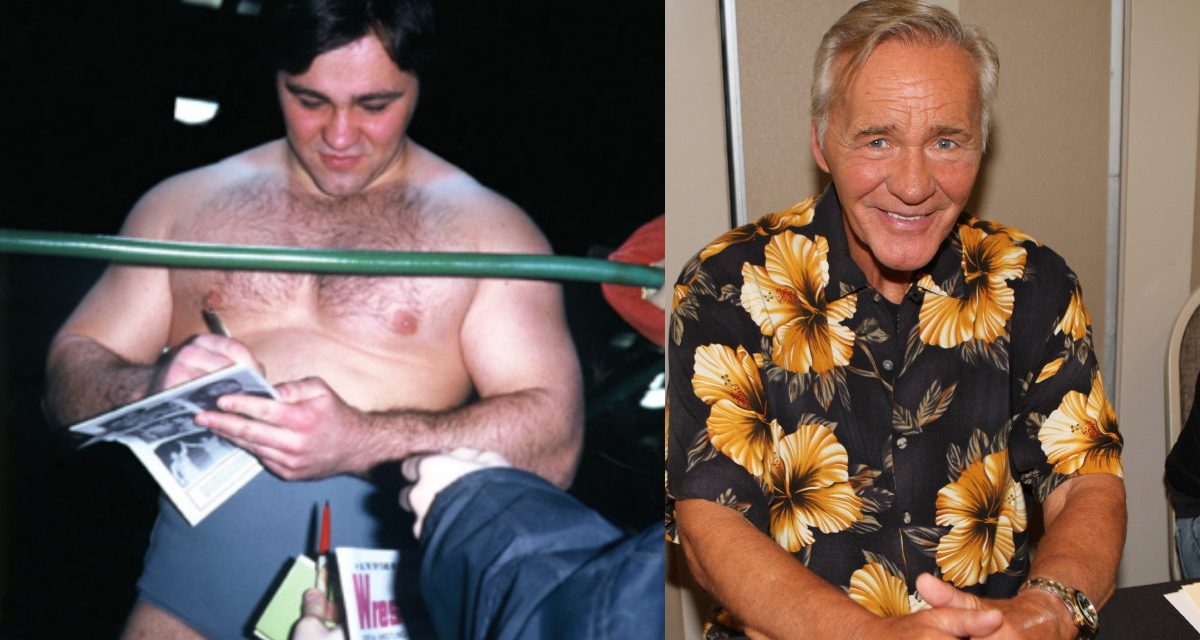

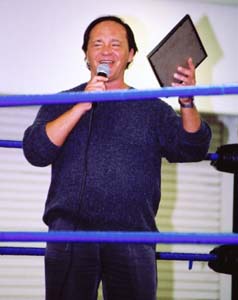

Zbyszko addresses the crowd in November 2003. — photos by Steven Johnson

A scratch golfer, Zbyszko has been playing in professional mini-tours and senior tour qualifying events in the southeastern U.S. as he reaches the eligibility age of 50.

“The golf game is great,” he said in a recent interview with SLAM! Wrestling. “Plus, it’s nice not getting hit in the head for a living.”

A crossover from the squared circle to the links would represent the ultimate transformation for Zbyszko, who held world championships in all the major federations. But, given his 30-year record of successful setups and swerves, fans understand that Zbszyko always has one more surprise up his sleeve.

“You never know,” he said. “Next year, I could be walking down with Hale Irwin and Fuzzy and putting them in sleepers.”

In private, Zbyszko sounds much as he did as an Atlanta-based announcer for WCW in the 1990s — measured, articulate, with a wry and often piercing sense of humor punctuating his remarks.

But he’s still extremely fit and ready to go to the mat, whether it’s for occasional ring work or his lawsuit against the WWE and owner Vince McMahon for control of the “Living Legend” moniker.

Growing up in Pittsburgh, Zbyszko, as Larry Whistler, wanted to be a pro wrestler, even when he was a pint-sized ninth grader. “I was about 130 pounds dripping wet and told my guidance counselor that’s what I wanted to do. He was laughing at me, but that’s what I really wanted to do.”

To pursue his goal, Zbyszko and friends started hanging around the house of WWWF wrestling legend Bruno Sammartino, a longtime Pittsburgh resident and one of the sport’s greatest icons.

After years of training with Sammartino, it was natural that Zbyszko was billed as “Bruno’s protege” after he turned pro in 1972. His baby-faced good looks and association with Sammartino catapulted him to hero status, and he eventually captured a share of the WWWF tag titles with Tony Garea in 1978.

But Zbyszko knew that that he’d never reach the top of his profession as long as fans regarded him as Sammartino’s understudy. In the winter of 1979-80, with his career growing admittedly “stale,” Zbyszko became the embodiment of treachery in one of the most unforgettable rivalries of “old school” wrestling.

In a humble television interview, Zbyszko politely asked his mentor to wrestle him, saying it was the only way he could step out of Sammartino’s shadow and establish his own identity.

At first, Sammartino demurred, but he recanted when Zbyszko declared that he would quit wrestling if he couldn’t square off with the two-time WWWF world champion.

In January 1980, Sammartino wrestled Zbyszko in a match taped for television, with the proviso that it would be a scientific, “exhibition-style” contest.

For several minutes, Zbyszko became increasingly frustrated at his inability to gain the upper hand. He’d try a hold, and Sammartino would counter. He’d try to break a hold, and Sammartino would clinch it in tighter than ever.

Finally, it happened. Sammartino flung Zbyszko through the ropes. Zbyszko grabbed a wooden chair, and with a pair of whacks to the legend’s head, froze a moment in wrestling time and changed his life forever.

“During the match I was so programmed to be a professional,” Zbyszko said. “Later on that night, after I got home and I’m relaxing and I’m coming down from all the adrenalin, then it dawned on me. I said, ‘Holy cow, I hit Bruno over the head with a chair. I’m the most hated bastard in the world.’ ”

Truer words were never spoken. Chair shots were a relative rarity then. The turncoat went from beloved to despised in a matter of seconds, especially to the heavily ethnic northeastern U.S. audience that idolized Sammartino.

Outside of arenas – even in his hometown of Pittsburgh – Zbyszko’s car was pelted with rocks and debris. An incensed crowd overturned his cab one night in April 1980 outside the Boston Garden.

In Albany, N.Y., Zbyszko took a knife to the buttocks in a wild melee after a match with Ivan Putski. An irate fan jumped Zbyszko as he left the ring area, and Zbyszko responded by flooring him. Security officials dragged away the offender, leaving Zbyszko unprotected in the middle of a venom-spewing crowd.

“So I started freaking out, because the more you freak out, the more people back away,” he reasoned. “I had just made it to the point where I was away from the crowd, and I felt like someone kicked me in the ass.”

He went downstairs to a dressing room in the musty old Washington Avenue Armory, concerned that he had a “charley horse.” When he probed the injury, he pulled out a four-inch blade that had broken off in his buttocks.

“Remember those wooden knives that would fold, with the handle and skinny blades? Well, he stabbed me with that,” Zbyszko remembered with a belly laugh. “Oh, but, it was a fun career.”

The payoff match with Sammartino came on August 9, 1980, in a steel cage that drew 40,000-plus fans to Shea Stadium in New York. While he and Sammartino have long since gone their separate ways, there is no question about the student’s respect for his teacher.

“He was great to work with because there was so much emotion that you didn’t really have to do a lot to blow the ceiling off of the building. Even if Bruno gave you a couple of arm drags, the people would go nuts.”

Indeed, part of Zbyszko’s appeal was the psychology he learned from Sammartino. While he had a solid wrestling background as an amateur, he believed practiced arrogance could incense fans quicker than a hammerlock.

For years, he regularly drew choruses of boos by intentionally stalling in matches, and demanded that referees ask his opponents for a submission even when he put them in the most inconsequential of holds.

But most of all, Zbyszko never missed a chance to remind the wrestling world that he had become the “New Living Legend” by his challenge to Sammartino, who often was referred to as a “Living Legend.”

Zbyszko let the words roll slowly off his tongue, his voice dripping with sarcasm — and it became the calling card for the rest of his career.

“It was a natural thing that I did, and I didn’t realize it at the time until it developed into a trademark. All I had to do was go on TV and say, ‘There you have it — you’re looking at the ‘New Living Legend,'” he said. “I rode the ‘New Living Legend’ and ‘The Living Legend’ for 20 years.”

Zbyszko is still riding it — right into federal court in Atlanta. After Chris Jericho won the WWE world title in 2001, he started referring to himself as “The Living Legend.”

A furious Zbyszko contacted acquaintances in the WWE and reminded them that the phrase had been his standing identity since 1980. In response, WWE lawyers demanded that Zbyszko stop using the “Living Legend” mark.

When Zbyszko filed a lawsuit against the WWE, McMahon appeared on television and personally presented Jericho, in a booming bass voice, as the “New Living Legend.”

The tit-for-tat left Zbyszko enraged because he was certain McMahon “was really saying to me, ‘Up yours!'” He calmed down considerably when he found his lawyer “dancing circles around his office” because McMahon allegedly had used the phrase at a time when he knew its ownership was in dispute.

Discovery in the case — including the introduction of 1980s-era Larry Zbyszko action figures with “The Living Legend” emblazoned on the package — is nearly complete, Zbyszko said. McMahon was deposed earlier this year.

Zbyszko said he would love to have McMahon in a final one-on-one in court, although there’s a possibility the issue could be settled before it gets that far.

“Vince has a monopoly now, so he does whatever he feels like doing, even if that means taking something I’ve been using for more than 20 years. You don’t see him being called ‘Macho Man’ Chris Jericho. It’s just the arrogance.”

Despite his box office appeal, Zbyszko never got an extended shot at Bob Backlund, the earnest, but uncharismatic, WWWF champion in 1980.

Coupled with differences with the McMahon family and the rise of densely muscled super wrestlers, Zbyszko moved on from the WWWF.

“I just never would build my body up with steroids,” he said. “To me, Shea Stadium, that match, that last angle, was the last of the big, real heat, real emotional, real ‘old school’ angles that was ever done. After that it became the era of Hulk Hogan and the ‘roid babies.”

Zbyszko didn’t take long to leave his mark in other territories. He headed to Georgia as the man who had “retired” Bruno, infuriating the territory in early 1983 when he “bought” Killer Brooks’ National Wrestling Alliance National title for $25,000 — a gimmick the WWE replicated in 1988 with Ted DiBiase.

NWA President Bob Geigel stripped Zbyszko of the title, but he won it back in a tournament in Atlanta a few weeks later.

Zbyszko had two strong runs as a cocksure heel in the Minneapolis-based American Wrestling Association (AWA) — it’s also where he met his wife — in the 1980s.

As the endgame in a long, carefully executed program, Zbyszko slipped a roll of dimes to the late Curt Hennig during a May 1987 match so he could knock out Nick Bockwinkel and win the AWA world title.

Ray Stevens, a Bockwinkel ally, rushed out to confront Zbyszko about his apparent interference, grabbed his coat, and shook loose some coins. Replied a smug legend: “Hey, everyone has change in their pockets.”

“It was just another example of how a classic angle is built up,” Zbyszko said. “We did it over months, we did it to the point where people were convinced I was going to beat Nick Bockwinkel for the title, I was going to win the belt somehow. And we turned it.”

Zbyszko was “suspended” for life in 1987 by the AWA after his sneak attack on Bockwinkel, who was winding down his career. He returned in 1989, billing himself as the man who had “retired” both Sammartino and Bockwinkel, two first-ballot Hall of Famers.

“The Bruno angle was such a thing that even when I left the New York area and went to the AWA, as soon as I got there people would be chanting ‘Bruno!'” he said.

“And even though I wouldn’t bring up his name, all I had to do was open my mouth, ‘Yes, that’s right, people. You’re looking at wrestling’s Living Legend,’ and it would just be instant heat, which translated into people being at the arenas.”

When he won a battle royal for the AWA world title in 1989 — in typical fashion, he stalled and stayed out of harm’s way for most of the match — he gloriously announced: “This is better than retiring Bruno Sammartino! It’s more satisfying than crippling Nick Bockwinkel! I’m finally the world heavyweight champion.”

Zbyszko held the AWA’s top prize twice, then hooked up with WCW when the AWA folded in December 1990. In WCW, he teamed with Arn Anderson as “The Enforcers,” winning the WCW world tag championship in 1991.

They were named Pro Wrestling Illustrated’s Tag Team of the year, nearly 20 years after Zbyszko was tapped as wrestling’s Rookie of the Year.

In 1991, manager Paul E. Dangerously broke up the team when it lost the belts to Ricky Steamboat and Dustin “Goldust” Rhodes. A brawl between Zbyszko and other members of the “Dangerous Alliance” stable turned Zbyszko back into a fan favourite for the first time since 1980.

As Zbyszko made the transition from wrestler to broadcaster, he drew wild cheers every week by performing an elegant, exaggerated bow as he took his place on the WCW Monday Nitro set.

“As I got older and Bruno was retired longer and our audience became a little younger, with all the broadcasting on TBS and TNT and Nitro, then I kind of became ‘the Living Legend, the loved guy,'” he said.

“The new generation didn’t know Bruno. But they know me as the ‘Living Legend’ from a famous story that they really don’t remember, but they still talk about.”

Zbyszko, a licensed pilot, has been playing golf most of his life, and has the management of the now-defunct WCW to thank for honing his game in recent years.

“When Nitro came, I’d fly out one day, golf, do the Nitro show, then Wednesday go back for a couple more hours. I couldn’t ask for anything more,” he said. “So I lived on the golf course for 12 years and prepared to be 50 so I could give the senior tour a shot.”

Zbyszko is contemplating a move to Ponte Vedra, Fla., the home of the Champions Tour and a locale that’s a mecca for elite golfers. A move to Florida will put him within easy range of more mini-tours and events, more family and friends, and, of course, more trips to Disneyland for his children.

Zbyszko still wrestles from time to time — he made a well-received appearance in NWA-TNA earlier this year, and gets out to personal appearances on weekends when hackers clog the fairways.

“So I might as well fly out and make a few bucks, keep the wife happy … the kids keep eating, damn it!” he said facetiously.

RELATED LINK