| Lucha Libre: 1) style of wrestling pioneered in Mexico. 2) Spanish term for pro wrestling, which translates into “free fighting” in English. |

Combining a lightning quick pace with a ballet-like refinement, Lucha Libre is one of the most breathtaking, exciting and captivating wrestling styles to watch.

Part of what makes it such an enduring brand of pro wrestling is its universal appeal. Wrestlers from around the world migrate to Mexico’s sunny shores and amalgamate their respective wrestling cultures — be it Japanese wrestling, shoot-submission style, mat wrestling — with Lucha Libre, further expanding the boundaries of Mexican wrestling and creating a wonderful kaleidoscope of possibilities.

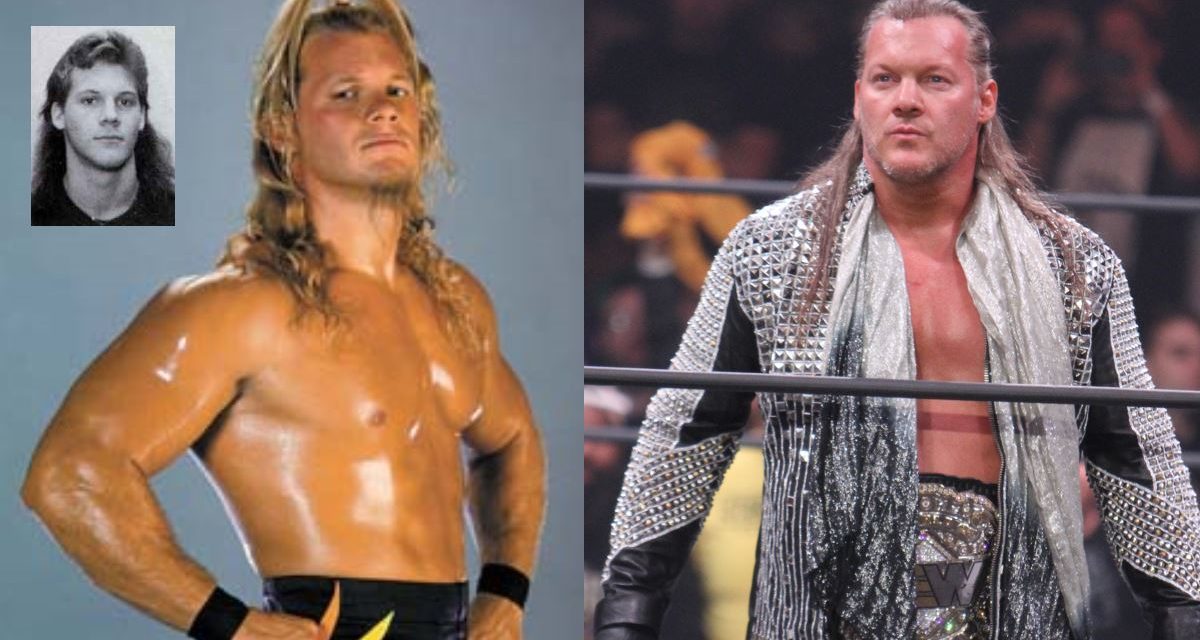

Chris Jericho wrestled for two and half years in Mexico’s EMLL promotion before signing with WCW in 1996.

Mexico has continually opened its doors to foreign talent, welcoming them with a warm embrace and providing them with an environment with which to excel. The list of Canadian and foreign wrestlers who have wrestled extensively in Mexico reads like a who’s who of the industry:

Chris Benoit, Chris Jericho, Owen Hart, Eddie Guerrero, ‘Love Machine’ Art Barr, Vampiro, Norman Smiley, Konnan, Ultimo Dragon, Jushin “Thunder” Liger, Satoru Sayama, Chavo Guerrero Jr., Vader, 2 Cold Scorpio, Val Venis, Louie Spicolli.

For years, many Canadian and American junior heavyweights had no alternative but to wrestle in Mexico and Japan and other foreign countries. Exiled from working in the WWF and WCW by bookers and promoters who believed they’d never get over with an American audience because of their size, several of today’s top stars received their first big break in Mexico. Because of Lucha Libre’s emphasis on athleticism, junior heavyweights’ lack of size is not a detriment, but an asset.

Chris Jericho’s first taste of success in wrestling came while working for Empresa Mexicana de Lucha Libre (EMLL). After training in the Hart Family wrestling camp in Calgary, Jericho toiled in the western Canadian independent scene for a year and half before venturing to Mexico in 1992 with the help of fellow Canadian Mike Lozansky who was working for an indy promotion based in Monterrey.

“I had just came back from a tour with FMW in Japan and went down there with Mike and started working for a month and a half,” Jericho told SLAM! Wrestling. “I got a call to go back down in ’93 and when I was there Mike met a friend of (EMLL owner Paco) Alonso who set us up and we started working for EMLL in April ’93.”

Billed as Corazon de Leon (Lion Heart), Jericho was a major star in EMLL, having brilliant matches against Ultimo Dragon, Silver King, Negro Casas and El Hijo del Santo and was NWA Middleweight champion for eleven months.

In between Mexican stints, Jericho worked for WAR and New Japan Pro Wrestling, the odd tour for promoter Otto Wanz in Germany and Jim Cornette’s Smoky Mountain Wrestling outfit in Tennessee. He wrestled his last match in Mexico in the summer of 1996 before joining WCW after a brief period with ECW.

Despite spreading himself all over the globe, EMLL was Jericho’s major bread and butter for two and half years. Looking back now, he feels his spell in Mexico was integral to his growth and development as a wrestler.

“I loved Mexico. I was 22 years old, I was working six, seven, eight times a week. At the time the economy was very good. It was a great experience wrestling-wise and life-wise… It’s a really good experience and a good way to build a solid foundation. I still use some of that stuff and can easily draw on it in the ring whenever I need to.”

“There’s some of the greatest workers in the world down there: Silver King, Negro Casas, Dr Wagner Jr., Emilio Charles. Those guys know how to work and they really gave me a good background in knowing how to work. It’s a credit to those guys down there because I came in as a main event guy at 22 years old, green as grass and those guys never took advantage of that. They helped me rather than beat me up… As a result of working with all of those guys, I was able to build a better foundation working with so many wrestlers.”

Wrestling as the masked Pegasus Kid, Chris Benoit was a regular in Mexico from 1991-1994 competing in the Universal Wrestling Association before jumping to EMLL. It was in the UWA that Benoit had a long, storied feud with Owen Hart, wrestling under a mask himself as the Blue Blazer.

Benoit also had a memorable program against Villano III in the UWA, winning his first world title, the UWA Light Heavyweight championship on March 3, 1991. The feud went on for months, climaxing in a historic mask vs. mask match on November 3 at the Quatro Caminos Bullring in Naucalpan that Benoit lost.

Like Jericho, Benoit believes his time in Mexico helped him become the wrestler he is today.

“Oh yeah, without a doubt it helped me. When you’re able to work all those different styles and grab a little bit from here and a little bit from there, and combine it into your style, it makes you different and makes you stand out… I’ve got fond memories and I don’t regret anything I did down there. I really cherish the time spent down there.”

Benoit says his tenure in Mexico helped open doors for him to work in Japan, Austria and Germany in the early ’90s when no American promotion would sign him because of his size: “It was great experience. I enjoyed my time down there. It’s a different style of wrestling, a different brand of wrestling, which I think helped better myself in terms of working in the international scene at the time.”

Chris Benoit under the mask as Pegasus Kid endures a camel clutch from Jushin “Thunder” Liger. Benoit and Liger are just two major stars of today that have wrestled extensively in Mexico.

“I have so many good memories of working down in Mexico, not only from in the ring but outside and camaraderie with the guys. Some of the guys who barely were able to speak English and I couldn’t speak Spanish, and having that bond and forging relationships was really neat.”

In spite of language and cultural barriers, Benoit says he didn’t have a difficult time adapting to life in Mexico: “I didn’t find it very hard at all. I found it very intriguing. What I like best about this business is the years I’ve spent traveling to foreign countries and not just learning different wrestling styles but I love meeting new people in the business from around the world.”

What Benoit did have a hard time adapting to was the ring style: “On my first tour I kept trying to wrestle their style, trying to find that medium and it just didn’t work. By the last week I started wrestling my style, but working within their brand of wrestling and it just clicked… It’s faster paced. It’s go, go, go, whereas in the States the psychology is different in terms of telling the story.”

Cuban-born Konnan is one of the biggest Lucha Libre stars of all time and is the biggest gate attraction in the history on Mexican wrestling. He first gained fame in EMLL before jumping to AAA (Asistencia Asesoria y Administracion) in 1992 where he became a cultural icon. Like Benoit and Jericho, Konnan wrestled in Mexico before coming to the U.S. in 1996 for WCW (he had a brief stint in the WWF as the original Max Moon but was let go by Vince McMahon) and is well versed in both Mexican and American wrestling.

He points out that the major differences between the two styles is that in Lucha Libre, moves are executed from the left whereas in the U.S. and Canada they’re performed from the right

“In Mexico, they work from the opposite side. That is to say when you arm drag somebody they do it from the left side, whereas here in the U.S. they do it from the right. In the U.S. when Mexicans come here, they see guys work the right arm and try to arm-drag a guy from the right. Mexicans don’t know how to do it that way because they’re used to working from the left.”

Konnan says there’s also a fundamental difference in ring psychology and how matches are put together.

“Over here the psychology is rest spot, get out of it, he brings you back down, you start pumping the crowd until you get that hot tag. Over there you have the heels beating up on you until somebody misses something and then the babyfaces make a comeback.”

“Mexican highspots are much more elaborate and longer,” continued Konnan. “And their false finishes are much more elaborate and longer than Americans. With Americans, when you give them a Mexican highspot or Mexican finish, they can’t remember it. Ours are longer and detailed.”

Eddie Guerrero followed in the footsteps of his father Gori and three older brothers by gaining his start in Mexico. Eddie first wrestled in EMLL in 1991 and later in AAA before moving on to ECW and signing with WCW in 1995.

Eddie Guerrero while wrestling for the AAA promotion in Mexico.

Guerrero believes spending his formative years in Mexico gave him a decided advantage over other American wrestlers: “Lucha Libre was a wrestling style that was different and gave me another side to my repertoire. If you can use the Mexican style and adapt it to any style, be it American or Japanese wrestling, it’s great.”

For years, like Benoit and Jericho, Guerrero split his time between Mexico and Japan, as he was unable to get a spot in either the WWF or WCW because of his size. Mexico allowed him to earn a living in wrestling when so many doors were shut to him in the U.S., a fact still not lost on Guerrero.

“I thought I’d never be working in the States, to be honest with you. Never in my mind could I see myself working in the U.S. Never. It was a big man’s business here, and I knew it. So I didn’t get my hopes up. I knew that my business was going to be in Mexico and Japan so that’s where I put my focus on. Then all of a sudden the doors opened up here and I couldn’t really believe it.”

Guerrero also believes Mexican wrestlers have not been properly attributed for being the innovators that they are.

“You have moves that originated in Mexico that are named after people here. Give me a break! You have the Frankensteiner? Where does that come from? It’s a Huracanrana, that’s from Mexico. Or the Swanton? You don’t think there are guys in Mexico that have done that before? The basic move is a Mexican move.”

Guerrero argues one of the big differences between Mexican and American wrestlers is their level of professionalism and attitude about doing jobs.

“Guys are really professional over there. You have to earn their respect, though. Once you do that they’re great. They’ll help you out and give you the shirt right off their backs.”

Konnan agrees. “The locker rooms in Mexico are cliquish but it has nothing to do with power; it’s built more around friendships. In the U.S., people band together so they can have power. In Mexico, I would say it’s more laid back and lot more fun.”

Konnan also believes their isn’t as much of a negative stigma about doing jobs in Mexico.

“It’s bad enough (the top American stars) won’t do a job, they won’t even make a guy look good. I think the most professional thing you can give back to this business, which has given you so much, is putting someone else over when it’s your turn. I made a living in Mexico out of putting people over because when they beat me, they became famous and I still held on to my spot.”

Despite its popularity in Mexico and Japan, Lucha Libre is a much maligned wrestling style in the rest of North America. Both fans and wrestlers alike in the U.S. and Canada point to the confusing rules, dizzying array of highspots, lack of ‘proper’ psychology and choreographed sequences in its constant criticism of the style.

It’s not ‘real’ wrestling, many argue. It’s gymnastics.

Jericho is quick to defend Lucha Libre against those that don’t think it’s a ‘real’ form of wrestling.

“Just because you don’t understand something doesn’t means it isn’t legitimate… It’s a different style and that’s part of the beauty of the business. As a worker, you have to understand that not everybody wrestles our style. There’s a German style, an English style, a Japanese style, a Mexican style. Everywhere you go it’s different.”

“There’s a very important saying in wrestling that there’s more than one way to skin a cat,” said Dave Meltzer, editor of the Wrestling Observer Newsletter, during a live chat with SLAM! Wrestling last week. “For example, when WWF was on fire two years ago, that doesn’t mean their style was the ‘only’ style of wrestling that can work.”

“Lucha style is different. (Americans) may look down on it because the nature of the wrestling as they were taught, the Lucha stuff doesn’t look realistic enough, but if it works, more power to it. Wrestling has been an important part of (Mexican) culture for decades and it still draws well and if you look at this as the business it is, you don’t have to like what works and it may not be your cup of tea, but you should respect that it works.”

While in WCW, Konnan saw first hand the disrespect American wrestlers had for Lucha Libre.

“I’ll never forget at the Great American Bash pay-per-view in 1996, when Rey Misterio Jr. took on Dean Malenko. When Rey walked into the dressing room, everybody was laughing. He was small and they were all making jokes about him behind his back. They didn’t know we were good friends. The jokes just went on and on. I told Rey ‘they’re back their laughing and they think this is a joke’. They thought Luhca Libre was a joke. I told him to go out there and to show them why Lucha Libre is the most exciting wrestling in the world.”

“In the five years I was there, I’ve never seen this… when Rey came back to the dressing room, everybody in the dressing room was giving them a standing ovation. When you can get a bunch of wrestlers to pop who don’t sell anything in the ring, that tells you these are special guys.”

The Lucha Libre style has also influenced wrestlers that have never even competed in Mexico.

“There’s definitely stuff we’ve picked out from the Lucha Libre style,” admits Jeff Hardy. “It’s quite a different style from what the WWF promotes, but there’s a lot of things that I think we can pick up and use in our style.” Jeff also defends the legitimacy of Lucha Libre: “I like it. Wrestling is entertainment. Who’s to say what’s right and wrong? There’s so much creativity and originality in it.”

Brother Matt concurs.

“When I first saw Rey Misterio Jr. and Psicosis in ECW I loved it. I fell in love with Lucha Libre. It’s just a perfect mix to throw some of that in with the American psychology.”

Lita had informal training in Mexico before turning pro and says she integrates parts of Lucha Libre into her matches.

“Their style is so different from the WWF style that you could not be able to use a lot of it. But you can take it and tweak it and put it in the right spots. You might build a match here in the U.S. to work around this one spot that you saw up there that was one of their opening spots. It’s neat to take what they have to offer and to take the mindset of the people in the WWF and incorporate the two.”

Favourite memory/match

Chris Jericho: “A two-out-of-three falls match in July of ’93 had me and Ultimo Dragon against Negro Casas and El Dandy that went 55 minutes in Mexico City. It was actually voted match of the year in one of the Mexican wrestling magazines. I don’t think we had too much called, maybe ten minutes worth of stuff. The other 45 minutes was just working holds and exchanging.”

Eddie Guerrero: “I’ll always remember the feud my partner Art Barr and I had against Octagon and El Hijo del Santo. That was great. I loved that. We stretched it out for two years. I’ll always remember that program; it’s embedded in my memory for life.”

Chris Benoit: “Working with the Villanos, especially Villano III. We had one match at the Quatro Caminos Bullring in Naucalpan that was voted best scientific match of the year in one of the magazines.”

Konnan: “AAA running Los Angeles for the first time in August ’93. More than anything that stands out because I had to come back to the U.S. to prove McMahon was wrong in letting me go. I knew I was a draw in Mexico but when I went to L.A. and someone came up to me and said the building is sold out with 16,000 fans and there’s 8,000 people outside that want to get in… I couldn’t believe how incredible that was.”

Dictionary of moves

Cangrejo – a Boston Crab. A half Boston crab is known as “medio cangrejo”

Gory Special – Back-to-back backbreaker submission, invented by Gori Guerrero

Huracanrana/Huracarrana – A Frankensteiner finishing in a double leg cradle (rana)

Mortal – Any 360 or 180 flip (a moonsault, a somersault bodyblock, etc.)

Pescado – Slingshot bodyblock

Plancha – Any move in which the attacker connects with his chest/abdominal area, like a splash or a cross body block

Quebrada – A moonsault after springboard off the second drop. Also called Asai Moonsault as it was popularized by Yoshihiro “Ultimo Dragon” Asai

Quebradora – Generic term for backbreaker

Quebradora con giro – Tilt-a-whirl backbreaker

Salida de bandera – Over the top rope bump

Suicida – [Suicide] Particle added after a move (usually a tope or a plancha) to state that it’s from the ring to the outside

Tope – Any move in which the attacker hits his opponent with his head

Tope con giro – Literally, Tope with a twist

Tope suicida – Tope to the outside

Tapatia – An inverted surfboard

Tornillo – Any spinning or corkscrew move

– Courtesy Jose Luis Fernandez, highspots.com

RELATED LINKS