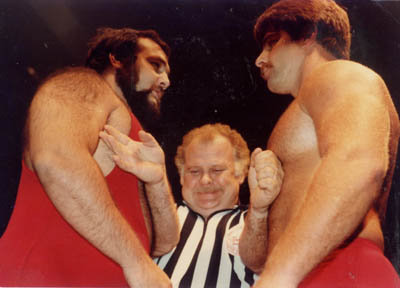

Pierre ‘Mad Dog’ Lefebvre, left, and Raymond Rougeau face off. — all photos courtesy the Rougeau Family

REAL NAME: Pierre Lefebvre

BORN: February 24, 1955 in L’Assomption, Quebec

DIED: December 24, 1985

ALIASES/NICKNAMES: Mad Dog

Pierre ‘Mad Dog’ Lefebvre and Raymond Rougeau were born six days apart in 1955. From Grade 4 in St. Sulpice, Quebec until Lefebvre was killed in a Christmas Eve car accident in 1985, the two were best friends, and their wrestling careers were deeply intertwined.

But Lefebvre was much than just Raymond’s best friend. He was an additional Rougeau family member, often staying at the Rougeau household for an entire week.

Lefebvre was the youngest in his real family, and his father died when he was about five. His mother re-married, and when Raymond met the Lefebvre family for the first time, only one sister was living at home with her mother and step-father; a brother and sister had already left the household.

And so young Pierre found himself hanging out with his new best friend Raymond, and the large Rougeau family. “He was always with me,” Raymond Rougeau recalled for SLAM! Wrestling. “Actually, he lived five minutes walking distance, but he always slept over. He had his own bed. We were like four boys at home. Instead of Jacques, Armand, myself, it was Jacques, Armand, Pierre and myself.”

But Lefebvre also made an impact on the Rougeau sisters, Diane and especially Joanne. “For more years than I can remember, he was as close to me as a brother than Raymond was,” Joanne Rougeau said. “They even let me tag along with them most of the time when fishing, boating or just everyday enjoying the fun things of growing up.”

At 15, Joanne’s feelings for the 17-year-old Lefebvre had deepened to much more than a brother-sister relationship. “We kept our puppy love, heavy duty crush under wraps, in front of Raymond anyways,” Joanne said. “My mom was pretty understanding and helped Pierre and I keep our secret. After a while it became difficult to keep playing brother and sister only and we decided to try keep our relationship brotherly only, so we never lost the feelings of closeness we felt we had.”

From left: Denis Gauthier, 31, Joanne Rougeau, 16, Pierre Lefebvre, 18, Paulette, Raymond, 18

Raymond and Pierre starting training in the ring and with weights together at 14 years of age. Both were strongly influenced by the wrestling careers of the Rougeau family — their father Jacques Rougeau Sr., uncle Johnny Rougeau and their great-uncle Eddie Auger. At 16, Raymond wrestled his first match, and starting training his best friend. Lefebvre debuted a year later at 17.

Sailor Ed White broke into the wrestling business in Montreal in the early 1970s as well, and remembered being impressed by the young Lefebvre. “He had everything. He had the looks, but I thought he was going to be more of a babyface than he was a heel. He started off babyface for a while, but then when he turned heel, he improved, got better.”

So Lefebvre took to the ring like a fish to water, and seemed to be headed for the top. Raymond had the connections, and he was learning and improving each and every time in the ring.

But then in 1973, Lefebvre surprised his best friend, and quit the business. For two years, he was a welder. “He got married and his wife was on his case to get off the road and be home,” explained Raymond.

In 1976, Raymond was in Atlanta working for Jim Barnette, and he would correspond with Lefebvre. It was obvious that his friend missed the business. “He told me if there was a way to get booked in Atlanta, he’d love to come down there,” recalled Raymond. So in the fall of 1977, Lefebvre and his wife, Raymond and his girlfriend left for Atlanta, where they stayed for two years.

It was on their return to Quebec that Pierre Lefebvre made himself a big name. Most of the thanks goes to Michel ‘Le Justice’ Dubois, who asked the Montreal promoter Gino Brito to team with Lefebvre.

Dubois was one of the hottest heels on the circuit. “If you want to build somebody, put them with somebody’s who hot,” Brito explained of the pairing.

“It got over big here in Montreal, it got over real big,” said Brito. “Every Monday at the Paul Sauvé Arena, they were one of the staples there.”

It took an attitude shift for Lefebvre to succeed. “He realized that he had more room as a heel than as a babyface, so I kind of took him under my wing,” Dubois said. “We called him ‘Mad Dog’ because we knew Mad Dog Vachon was coming in the future. So automatically we knew to built to a match between the two Mad Dogs.”

The Mad Dogs were pretty evenly matched, Dubois remembered. “They were both short — when I say short, they were both 5’10”, 5’11”– they were both stocky, both hairy, both with a beard, both acting like a dog.”

Maurice ‘Mad Dog’ Vachon did indeed come in for the summer, partly to seek revenge the punishments Dubois and Lefebvre had dished out to his son Mike Vachon, who was breaking into the business in the territory.

Vachon was initially not pleased that another wrestler was stealing his nickname. “I didn’t like it at first, but after that, I said ‘Why not?'” said the wrestling legend. “Then we had quite a few matches and return matches, one against the other, so it served a good purpose. We packed them in, so what the hey, it came out smelling like a rose.”

Promoter Gino Brito said that the feud with Vachon was the turning point in Lefebvre’s career, and the improvements were noticeable. “He got a lot of confidence and he started to move pretty good. Everything about him, including his interviews on TV, got better.”

To Vachon, Lefebvre was a very good wrestler. “He was very dependable, professional and he always showed [up for the matches]. He had a lot of energy in the ring. … he could take a lot of punishment. He was a credit to the profession.”

Raymond Rougeau also thought highly of Lefebvre’s work in the ring. “He was a very professional wrestler. He took his business very seriously, very dedicated to the business. He was an excellent worker. He had very good ring psychology, intense in the ring, worked solid and was always willing to improve on his style, on his technique or anything.

“When I had him booked in Atlanta, Ole Anderson was booking then. I told Ole that I had a friend of mine that would like to come down with me. He says, ‘Can he work?’ And I said, ‘Take my word for it, he’s a good worker.’ When he came down, Ole says, ‘Jesus Christ, this guy’s good!'”

From 1981 to 1984, Lefebvre held the International Wrestling tag team belts on three occasions, with three different partners — Pat Patterson, Billy Robinson and Frenchy Martin. He feuded with the likes of the Rougeaus, Gino Brito, Tony Parisi, Dino Bravo and others.

Lefebvre continued to improve, and Brito teamed him up with manager Tarzan ‘The Boot’ Tyler. The elder Tyler, who had been involved with wrestling for years and years, took on Lefebvre as a protege.

In 1984, Lefebvre found himself in the peculiar position of babyface after his fellow stablemates in Tyler’s group, Sailor White and Rick Valentine (Kerry Brown), turned on Frenchy Martin. Subsequently, the Quebecois team of Lefebvre and Martin sought revenge against their English foes, aligned with Tyler.

Pierre Lefebvre

‘Mad Dog’ would later be teamed again with manager Tyler, and be was a hated heel when Christmas 1985 came about. Tyler, Lefebvre and referee Adrien Desbois were on their way home from the matches at Centre Georges-Vezina in Chicoutimi on the evening of December 24, 1985 when they were in a terrible car accident. Their Ford Escort rammed a tow truck at 1:25 a.m. on an icy Route 175 in the Parc des Laurentides. All three men were killed; the driver of the tow truck was unharmed. The news quickly made the rounds, especially with the tragedy coming so close to Christmas.

“I was at work at about 6 a.m., in Dorval and heard the news on the radio,” Joanne Rougeau remembered. “I called Raymond and he had just been called himself with the news. I cried silently in my office most of the day (and night). When I went to the funeral home, I was alone and in denial, grieving for the loss of a love, a close friend and a brother in one.”

Lefebvre, only 30 at the time of his death, was survived by his wife, Micheline, and two children — his son Sebastian, who was six, and his daughter Caroline, who was three.

Sailor White had high praise for Tyler and Lefebvre. “Two of the greatest wrestlers that I’ve had the privilege of knowing. They had wrestling in their hearts. They were not quitters. They were super entertainers. They didn’t give 100%, they gave 150%.”

There is no question that Pierre ‘Mad Dog’ Lefebvre was destined for greatness in 1986. The WWF was expanding, wrestling was booming, and talent all around him like Rick Martel and Dino Bravo was getting scooped up.

Jacques and Raymond Rougeau went to the WWF three months after his death.

Gino Brito believes that Lefebvre’s opportunity would have come. “I would have predicted that he would have had a break eventually … he wasn’t that tall, that big, but he was getting better and better.”

“He died just before his prime,” Raymond Rougeau said. “He had what it took and all he needed was a break. He got a break locally here and the next step would have been a break internationally. I’m sure he would have had it.”

RELATED LINK

30 years later: The car crash that killed Tyler, Lefebvre and Desbois

Memories

I remember when Lutte International came to Edmundston, New Brunswick and Lefebvre and Frenchie Martin were the tag team champions. The crowd hated them, people used to scream and get excited every time the heels would get beaten. They eventually won by disqualification and everyone was mad at them. I was nine back then and after the match he was going back to the locker room and I was in his way. Instead of growling and trying to scare me, he just got politely moved so he could go through. I was sure he was going to kill me. It’s probably because he loved children and didn’t feel the need to act like a heel all the time. I’ll never forget that day when we heard of the radio about the accident. It was Christmas Eve and everyone was talking about it.

mplourde