Getting to the Olympics as a Greco-Roman heavyweight was a natural progression for Bob Roop.

He started in wrestling in the eighth grade in East Lansing, MI, where his father worked at Michigan State in the engineering department. Roop succeeded at the state-level in high school, and entered Michigan State on a football scholarship. After a year and a half as a Spartan, he left school to join the Army. After his three-year stint in the service, he entered Southern Illinois and got down to work as an amateur wrestler.

“As you achieve more, certain things become possible,” Roop explained to SLAM! Wrestling from his Michigan home. “After wrestling in the national tournaments for several years and doing well, I had tried out for the Olympics in ’64 and was an alternate, and really didn’t have a clue about what I was doing then. For ’68, I had been training hard for it for about two years. By that time, again, I had wrestled most of the top heavyweights in the country, so I had an idea of the competition and I had a realistic goal in my mind of what I could accomplish.”

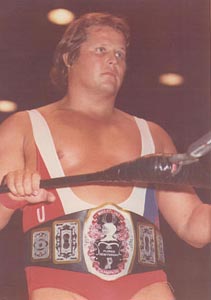

Bob Roop

For Roop, it was the opening ceremony of the Games in Mexico City that really stands out for him. “It was pretty spectacular,” Roop said. “The entry into the stadium the first day was pretty overwhelming … it was just awesome, a very nice feeling.”

Because the Greco-Roman events took place during the last week of the Olympics, he found himself training instead of socializing in the Athlete’s Village. “We spent most of our time there training twice a day, so there wasn’t a lot of time. You got up, had breakfast, and trained in the morning and then came back and rested and had lunch, then wrestled some more at an afternoon training. In the evening, we had the chance to socialize. All the athletes would get together in the community hall and swap pins and get to know one another.”

Roop was 25 and weighed 270 pounds entering the Games in Mexico City in 1968. Believe it or not, he was a small heavyweight.

“I wasn’t a heavyweight. I was about 6’1″, and most of the good heavyweights in Greco-Roman — not so much freestyle, because you don’t need to be tall, there’s a premium on movement there. But in Greco-Roman at the heavyweight level, there’s a lot of pushing, at least there was at that time. To be tall gave you leverage, and then all these guys weighed 300, 350, one guy weighed 420. I was too small.”

Roop finished in seventh place in Mexico City, losing to a seven-foot, 340-pound Russian named Aleksander Medved, who went on to win the gold medal.

It leaves a big ‘What If?’ in his life — What if he had stuck around another four years to compete in Munich as a lighter wrestler?

The potential was there. During his last year of college, his coach at Southern Illinois convinced him to train down to a lighter weight of 220 pounds. “That spring, I entered my last national tournament before turning pro, the national AAU at Greco-Roman at 220, and I won that one. It was the first one I even won. I had taken second and third a couple of times,” Roop said.

But his life had started in earnest by then. He was married and had a young son (who was born just days before the Olympics in Mexico City started). Roop turned down an offer to continue training in Detroit that came with a job.

Fate then intervened, and he ran into an old friend, Larry Heiniemi, who had been an amateur wrestler and was now a pro named Lars Anderson.

“He looked great. He had gained about 40 pounds of muscle, bleached-blond hair — not that that attracted me! He was a changed guy,” recalled Roop. “He had been an 180-pounder or something, or maybe 198, who was kind of a nondescript kind of guy. Here he was driving a big Cadillac, sporting a big diamond ring. All the accouterments of success. But he told me in two years he had made $75,000, also that he had gone to Japan twice and Australia twice. It was the latter part that interested me because my major when I graduated was … in international political science, heading into travel. Sounded like a way to do both.”

Armed with a new goal, and his B.A. to fall back on if need be, Roop accepted an offer from Florida Championship Wrestling promoter Eddie Graham to come down for a visit. “I was given the chance to watch the match and see what was going on, get a feel for things and then to make a decision. The main thing for me was the money they guaranteed me to start. It was a guarantee, I didn’t have to earn it.”

So he turned pro in 1969 and wrestled until 1988, when a car accident damaged his neck. But still he kept involved, and worked as a promoter and as a trainer in Florida. In fact, it’s likely you’ve heard of at least one of his students — Larry Pfohl, aka Lex Luger.

Roop estimates that he wrestled over 3,000 matches in his career, and was a heel for a good part of them. In his best year, he figures that he made $80,000, but most years were in the $50,000-$60,000 range. On five occasions, he fought for the world title, but never came out on top.

In Florida, he was the state champion on numerous occasion, and formed a successful tag team with Bob Orton Jr.

Then in the mid-’80s, he agreed to try something new. Kevin Sullivan was putting together a ‘Cult’ in Florida, and together, they came up with the idea of Roop converting into Maha Singh.

“It was really a fascinating gimmick, a multiple-personality disorder that manifests itself physically, looking like a Caucasian Bob Roop on one side, and this maniac Maha Singh on the other,” Roop remembered. “You could talk different, you can go from the way I’m talking now to talking like snarling and growling. In the ring, you could wrestle like an Olympic wrestler might wrestle, and then turn into a maniac, kicking and chopping. It had great potential for a gimmick.”

Things didn’t go as planned for the gimmick, however. “When we got into a position to use it, Sullivan stabbed me, he just didn’t use it. He wanted to do all the talking himself, so he didn’t want Bob Roop on the scene so it never got used.” Three months later, Roop was made booker/matchmaker for the Florida territory. “When I got the book, I fired him!” he said laughing.

Others in Sullivan’s Army of Darkness included Sullivan, Purple Haze (Mark Lewin), Luna Vachon & Lock (Winona Littleheart), Kharma (Gene Lewis/Gene Petit) and Fallen Angel (aka Nancy Sullivan, Woman).

In the dressing rooms during his days, the Olympics and his Olympic experiences never came up much. “We never talked about it. I don’t know why,” Roop said.

He went on to explain the stigma that wrestling put on successful amateurs. “One of the things that was common for the boys, the pro wrestlers, to say — and it was true in many cases — was that an amateur will never make it as a top pro. He might make a living, but he’ll never be a top pro. In most cases, that’s true. Guys already have a persona that’s grounded in a lot of sweat and toil to get to the Olympic level. It’s hard to shove that aside and really pretend well to be someone else.”

Roop believes that the late Dale Lewis, who was a U.S. Olympian in 1956 and in 1960, was the ultimate example of that stigma. “Dale had to be a pro that was just so-so. I’m not knocking him, but when I first began, I was having matches with him and here I was green as grass, I didn’t have a clue what I was doing out there, but I would have matches with other guys who were much less athletic, older, not in as good of shape, that would be great matches. I would have these matches with Dale, and people would tell me ‘You ought to be ashamed of yourself,’ even though I beat him. … He didn’t know how to make me look good, and I didn’t know to do that myself.”

Sometimes the NCAA years were discussed, but not much. “Jack Brisco was a pal of mine when I first started. He had been an NCAA champion, but we didn’t talk about that either. Maybe once in a while maybe for a few minutes, talking about some guy we knew in common or about a coach or a meet or team we’d both wrestled against.”

Now 58, Roop can appreciate all that he’s accomplished. He has three sons, one from a previous marriage that has children of his own, and two boys at home now, aged 11 and 7, with whom he spends a lot of time. He’s retired, and works as a lunch-room supervisor at his kids’ school. Other passions include being a Scout leader and researching his family history.

Like almost any older wrestler you talk to these days, he’s also working on a book. But, unlike the slew of other wrestlers working on their biographies, Roop’s dream is to write a mystery novel that is set in the wrestling ring. Ten years ago, he wrote his first novel, called Tales From The Mat: Rookie Daze. It got some interest, but he said publishers would always bring out the old excuse: “We don’t believe your target audience buys books.”

Roop has been around long enough to have seen the wrestling business in its highs and lows. “Wrestling has gone in cycles. It has gone from being very flamboyant — Gorgeous George and all his imitators were about as flamboyant as you can be in an age before pyrotechnics, and people swinging into the ring from above the arena, coming down on a wire.”

“They got so flamboyant that they killed it off, and went back to just a pair of tights and pair of boots and a bunch of wrestling holds until the popularity came back. It just goes in cycles.”

But he’s honest enough about it too. “I would love to be in my heyday now.”