What might have been?

That’s the question Eddie Guerrero asks himself every day.

What if he hadn’t died? What if he hadn’t lived the fast life? What if his friends could have straightened him out?

What if?

“You just gave me chills (mentioning him),” Guerrero told me over the phone recently. “I’m looking at his picture right now in my office.”

It seems odd that a picture would choke up someone like Guerrero. But when that picture is of former tag team partner ‘Love Machine’ Art Barr, nothing more has to be said.

November 23rd marked the fifth anniversary of the death of Art Barr. For Guerrero, the death of his best friend is still a painful memory. They were close. Very close.

“He was like a little brother to me,” said Guerrero, trying his best to fight back the tears. “We lived together (in Mexico) for three years. If I wasn’t with my wife I was with him. We were each other’s family.”

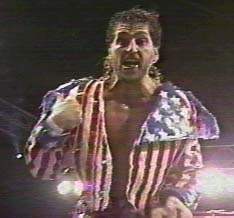

Love Machine Art Barr from the AAA When World Collide PPV.

Barr and Guerrero comprised La Pareja del Terror (The Tag Team of Terror) arguably one of the top tag-teams of the 90s. Plying their trade in Mexico’s AAA promotion, Barr and Guerrero set Mexico on fire.

Barr was largely responsible for advancing the style of wrestling in Mexico. He was a true pioneer, combining the acrobatic, ballet-like grace of Lucha Libre, the stiffness of Japanese Puroresu and the big bumps and heel charisma of American wrestling into a revolutionary working style. More than anybody else, he helped change the landscape of wrestling in Mexico forever.

“He and Eddie broadened the style (of Mexican wrestling),” said Dave Meltzer, editor of the Wrestling Observer Newsletter. “Art opened their eyes to his style and made the young guys like Rey Misterio Jr, Psicosis and Juventud Guerrera who came up from AAA to WCW into the best workers in the world. He and Eddie had that much influence.”

Art’s influence even extended to his former tag-team partner.

“I learned so much from Art,” admitted Guerrero. “He could make the fans laugh, he could make them cry and he could make them pissed off. (He made me realize) there’s more to wrestling than just wrestling. He helped me change my personality in the ring. He had a big effect on me.”

At the time of his death, Art Barr was the top draw in Mexico and was generally regarded as the best heel in wrestling. His solid ring work, unmatched work ethic and ability to draw the audience into his matches made him an icon. He was charismatic heel. He was good. He was very good.

Eddie Guerrero from the AAA When World Collide PPV.

“I went to a lot of shows in Mexico he was on and he always worked very hard,” recalled Meltzer. “He was a better heel than the main event heels in WCW and the WWF at the time. He was one of the greatest heels I ever saw. He was a tremendous performer.”

Barr’s skills as a heel were renowned in Mexico. Noted for his facial expressions, his cocky swagger and his stiff bumping style, he used all of these tools to elicit visceral hatred from the audience. He had the unique ability of making every move he made in the ring mean something.

He had such heat, riots in the building were often common place. It was always a security risk whenever he wrestled. Sometimes he had to wait up to three hours after the event before he could leave the building safely. He was that over.

Together Barr and Guerrero had unbelievable chemistry, both complimenting the other. They were so special to watch, working together naturally and effortlessly.

“We knew our roles and accepted them,” said Guerrero. “He knew I was the work horse and I knew he had the charisma and life of the tag team.”

Konnan and others referred to him as ‘the Ric Flair of Mexico’. He was on top of the Mexican wrestling scene. But the path he took to get there was anything but smooth.

The son of referee and promoter Sandy Barr, Art practically grew up in the Portland Sports Arena, home of Don Owen’s Pacific Northwest Wrestling (PNW) promotion. He debuted on April 2, 1987 and after a year and a half was christened as Beetlejuice by former PNW alum Roddy Piper in a memorable TV angle.

Dressed in ripped jeans, face paint and flour in his hair, the Beetlejuice character was based on the Michael Keaton movie of the same name. Before each match, Art would sing and dance down to ringside, leading a trail of children to the ring like a pied piper. It was a character marketed directly at young children.

While it was his first big break in the business, it was hard to look at Barr, who excelled in amateur wrestling in high school, as anything but a cartoon character.

“You didn’t take him all that seriously,” said Mike Rogers, editor of Ring Around the Northwest, a monthly newsletter covering wrestling in the Pacific Northwest for the past 17 years. “He was a cartoon babyface so you didn’t really see that explosive personality come through like it did when he was the Love Machine.”

On July 16th, 1989 Barr’s life was inextricably changed forever. After an evening of matches, on a secluded stairwell in back of an empty arena in Pendleton, OR, Art had a sexual encounter with a 19 year old girl. She later filed rape charges.

Oblivious to the powder keg he was sitting on, Don Owen continued to use Art in the Bettlejuice character.

“We wanted to stick by him and not abandon him,” said Barry Owen, Don’s son and executive vice-president of PNW at the time. “He hadn’t been found guilty yet and we didn’t want to turn our back on him.”

Margie Boule, a columnist with the Portland based Oregonian newspaper who wrote several columns on Art’s pending rape trial offers a different view.

“They didn’t want to turn their back on somebody who could make money for them. They’d rather have turned their back on the young woman who was raped and the gang of children following him around the ring.”

A year later, just as the case was going to trial, Art plea-bargained down to first degree sexual abuse. Despite admitting during a police investigation that the woman did not consent, the Pendleton Judge ordered Barr to pay a $1,000 fine, pay for the victims’ hospital bills, placed Art on two years probation and sentenced him to 180 hours community service with youth organizations. He served no time in jail.

“I wrote how ironic it was that he had been sentenced to perform community service with youths,” said Boule, who received several death threats due to her columns. “Here was a guy who admitted he had raped someone. I wasn’t mad at him, if anything I was mad at the judge.”

His wrestling license in Oregon had not been renewed, not because of the case, but because he lied on his application about a drug charge as a teenager. A junior heavyweight and short in stature, there was no way that Art would ever progress in the steroid-big wrestler era of the late 80s/early 90s.

Miraculously, shortly after the trial, Art was hired by WCW as ‘The Juicer’, a gimmick based on the original Beetlejuice character. Boule wrote more columns condemning WCW for portraying Barr as a children’s character. A faxing campaign began as copies of Boule’s columns were faxed by anonymous sources to newspapers in the cities where WCW and Barr were scheduled to appear. Chants of rapist serenaded Art when he was in the ring.

Barr’s career was going no where. He was stuck in opening matches. He wasn’t being pushed. WCW booker Ole Anderson told Art he would never make it big because of his small size and that he would never draw a dime. Art had been hearing that his entire career. Wrestling was a big man business and it had no place for a small, yet capable performer like him.

WCW decided to cut their losses and terminate his contract.

As it turned out it was the best thing that ever happened to Art Barr. Konnan, a main event star in Mexico’s EMLL promotion, had brought Art to Mexico after meeting him in WCW when he worked a few shots there in December of 1990.

Barr donned a mask and was given the name ‘American Love Machine’. A year later he established himself as one of the top draws in Mexico as 18,000 fans sold out the 17,000 seat Arena Mexico in Mexico City and another 8,000 fans watched on big screen TV in the parking lot, as Art lost his mask to rival Blue Panther in a mask vs mask match. Somewhere in the U.S., Ole Anderson was eating crow.

Later that year, Art jumped to the new AAA promotion formed by Konnan and promoter Antonio Pena. After a short run as a babyface, Barr turned heel, was put in a tag-team with Eddie Guerrero and later helped form Los Gringos Locos with Konnan, a heel clique fashioned on the Four Horseman.

Los Gringos Locos broke all existing attendance records in Mexico. Art was receiving critical acclaim from the wrestling media for his work. He was on a guaranteed contract, making more money than ever before in his career.

Art was on top of the world. A high spot to fall from.

“He lived a fast life,” explained Dave Meltzer. “He was no angel.”

Despite all the success he had achieved there, Art hated Mexico. He was far from his son Dexter and his wife back in Oregon. He missed his mom terribly. He was homesick.

As a way to deal with the pressure of being far from home, Art turned to alcohol and prescription drugs. For Art, drugs and alcohol was an escape from the reality of being so far away from his family.

He was on a dangerous path of self-destruction. Those closest to him had tried to reach out to him.

“I would tell him, ‘Art, watch yourself’,” remembers WCW star Norman Smiley, who worked with Art during his days in EMLL and remained a close friend when Art jumped to AAA. “(It was like) you were talking to a wall. It was kind of frustrating because you wanted to help him, but you couldn’t because he would just continue to do what he was doing.”

“I just miss him,” said Vampiro, another friend of Art’s during his tenure in EMLL. “I just wish [breaking down], oh God, I just wish he listened when we told him to stop. And we tried to make him stop.”

As Art’s personal life was spiraling out of control, inside the ring he was on a whirlwind path in establishing himself as the best worker in the world. He went on his first tour of Japan with New Japan Pro Wrestling and was scheduled to work a program with Jushin “Thunder” Liger. AAA had worked out a deal with WCW where they would help them produce their first PPV.

On November 6th, 1994, AAA held their ‘When World’s Collide’ event, one of the most critically acclaimed PPV’s in wrestling history. And while Konnan faced off against Perro Aguayo in a cage match in the main event, the sold out crowd at the L.A. Sports Arena had came out to see Art and Eddie versus El Hijo del Santo and Octagon in a hair vs. mask match.

For Art, he saw the PPV as an opportunity. It was a showcase for him to show the rest of the wrestling world, particularly American promoters who told him he would never make it because of his size, how good he really was. He was tired of how American promoters dismissed his fame. He knew the only way they would believe it was if they saw it for themselves. He would have to put on the performance of his life.

And he did just that. The match was incredible, a five-star performance and ranks as one of the greatest matches in PPV history.

“Over the years I watch (that match) over and over again,” admitted Dave Meltzer. “You watch that match now and you realize there’s no matches now that are this good in the U.S.”

Barr had proved all the doubters wrong. He showed the American wrestling public, convinced that a small wrestler couldn’t make an impact, he was among the best workers in the world. The match had secured his legend.

As it turned out it was the last match he ever wrestled. On November 23rd, while home for Thanksgiving, Art passed away in his sleep. He had a mixture of alcohol and drugs in his blood stream. He was only 28.

“I cried three months straight when he passed away,” admitted Guerrero, breaking down.

Pundits still ask themselves where Art’s career would have taken him. There was no question he would be a major player.

“I think if he was still alive today he would be one of the top guys in the business,” said Chris Jericho a friend from EMLL. “He had such good personality and the ability to piss people off.”

“He would have had a hard time becoming the top singular PPV main event heel in the US,” offered Meltzer. “As a tag team, if given the opportunity, he and Eddie would have headed to WCW and if they weren’t politically squashed, they would have been the tag team of the decade.”

Art’s death received major media coverage in Mexico. He made the cover of Box y Lucha, the oldest wrestling magazine in the world, becoming the first non-Hispanic wrestler in the magazine’s 47-year history to make the cover.

Although he’s gone his memory still remains with the throng of Mexican wrestling fans who loved to hate him, proving his influence was immeasurable and his legacy is unquestioned. The only debate that exists is how big of a player he would have become on the American wrestling landscape.

What might have been, indeed.

— with files from Greg Oliver and Alex Ristic