I recently joined the Wrestling and Everything: Coast to Coast podcast with host Buddy Sotello, Esq. and wrestling polymath Evan Ginzburg for an episode devoted to the recent Netflix Mr. McMahon documentary.

Towards the podcast’s end, I was asked whether pro wrestling could have achieved mainstream success under a kinder, gentler leader.

Privately, I think that would have been wonderful. But history shows that’s not how pro wrestling works.

Buddy and Evan are avid fans with an encyclopedic knowledge of the pro wrestling business. They are often bothered by how heartless it can be.

Evan objects to Vince McMahon’s becoming a billionaire on the broken backs, bank accounts and spirits of generations of wrestlers. There are plenty of anecdotes about McMahon’s private generosity. They do not take away from the systemic issues that he leveraged to create an environment where wrestlers must mount social media campaigns to cover their hospital bills, rehab trips, mortgage payments or funerals.

Evan and Buddy are upset by WWE’s — and wrestling’s — descent into mediocrity under Vince’s watch; the waste of talent signed just to keep them from working for other promotions, the cut-throat approach to competition and the lack of loyalty that WWE shows many of its former stars.

While they recognize that things have improved since the company was sold and Vince (finally) left, their enthusiasm for new Chief Content Officer Paul ‘Triple H’ Levesque is muted. After all, Levesque is a product of Vince’s system and married the boss’ daughter, Stephanie.

At best, Buddy’s question is hypothetical. At worst, it’s entirely counter-factual.

The arena spectacles we watch today evolved from travelling carnivals, where the object was to separate spectators from their money. Wrestling clings to carny language today, describing fans as “marks,” “kayfabing” to protect wrestling’s secrets, and extending words to polysyllables with a bunch of z’s to keep a conversation private.

Wrestling is built on deception: convincing the audience that bouts and characters were real, while treading the line between illegal fixed fights and exhibitions that fell outside regulation. Even the most reputable, successful figures in the history of the business were in on this primal con. The promoters who are most often cited as “honest” within the industry, like St. Louis’ Sam Muchnick, Houston’s Paul Boesch or Portland’s Don Owen were key figures in the NWA — an entity that broke anti-trust laws. They all worked as part of the NWA to preserve their shares and took a portion of the reigning travelling champion’s earnings for their troubles, while excluding other would-be market entrants … so maybe they weren’t going to run things so nicely either.

WWE’s expansion combined ruthlessness with ambition. There have been plenty of ruthless promoters — especially when defending their turf. Most were content with their piece of the territories’ cabal. They lacked the scale of McMahon’s imagination.

If we look at Buddy’s counterfactual question, the most likely expansionists were promotions jockeying for position outside WWE. They were run by the likes of Jim Crockett, Jr., Fritz von Erich, Bill Watts, Jerry Jarrett and Verne Gagne.

Crockett was the most aggressive. He started expending territorially in the 1970s, and actively tried to counter McMahon’s attempts to monopolize the wrestling business. Crockett started in the Carolinas and Virginia. Between 1978 and 1983 he moved in on eastern Tennessee, parts of West Virginia, and Savannah, Georgia. Crockett next ran shows in Cincinnati and Dayton, Ohio, and bought minority shares of Frank Tunney’s Toronto-based promotion, Maple Leaf Wrestling. Mid-Atlantic Championship Wrestling also aired on a Buffalo, New York station, bringing the Tunney/Crockett/Scott enterprise to Ontario and upstate New York.

In the 1980s, Crockett, Jr. began consolidating the Southern member promotions of the NWA. In 1982, Crockett partnered with wrestlers Ric Flair and Blackjack Mulligan to start Southern Championship Wrestling, a secondary company out of Knoxville, Tennessee (although that lasted less than a year). Through the early to mid-1980s Crockett expanded aggressively, acquiring former NWA territories. By 1987, Crockett gained control of the St. Louis Wrestling Club, Heart of America Sports Attractions (Bob Geigel’s Central States brand), Championship Wrestling from Florida, and Bill Watts’ Mid-South Sports (which operated under the Mid-South Wrestling, and later, upon expansion, Universal Wrestling Federation brand names). Ultimately, Crockett over-leveraged himself through these acquisitions, an aggressive touring schedule, attempts to unseat WWE in the pay-per-view market, and overwhelming competition from WWE. He wound up selling his company to Ted Turner, and the rest is history.

Of the rest, Gagne likely has the best reputation, although he played favorites to the detriment of his business, shorted wrestlers’ payoffs to the point that at least two former champions — Jerry Lawler and Stan Hansen — held the AWA championship belt for ransom, and allegedly sought to have Hulk Hogan’s leg broken to thwart McMahon’s expansion. Watts is widely seen as dishonest, bullying and racist. Jarrett strongly influenced modern wrestling storylines but paid his talent near starvation wages. Von Erich’s flaws as a businessman and parent suggest that he was divorced from reality.

When we talk about promoters as nice guys we need to consider the difference between wanton cruelty and the hard decisions required to run a business.

Fans get upset when wrestlers are released from their contracts. For years WWE followed its supercards with mass layoffs. Bad enough when athletic, charismatic performers lose their jobs over Creative’s perceived failure to use them. Galling during the COVID-19 pandemic when there was nowhere else to work, WWE reported increased profits and smaller companies like ROH made heroic efforts to keep paying talent.

I hate to see anyone lose their jobs, but in wrestling, like other sports and entertainment, one is hired to be fired. Audiences demand a constant stream of new talent and storylines. Even the strongest acts eventually run their course. Promotions that grow reliant on a stable but stale group of legacy acts, like the AWA, quickly lose their audience.

I don’t think WWE can be responsible for its performers for the rest of their lives. A wrestler’s career may span decades. Longer tenures within WWE have become more common, but for most they are a fraction of a wrestler’s run. Talent who stick around long enough risk being shunted into less relevant roles. Ron “R-Truth” Killings has been with WWE since 2008. For more than a decade he has been comic relief. Nic “Dolph Ziggler” Nemeth spent almost 20 years with WWE and is a two-time world champion. Michael “The Miz” Mizanin is also a two-time champion with a 20-year run. By now both men have spent way more time advancing others’ careers than their own. Shinsuke Nakamura and AJ Styles have had shorter WWE careers but were among the best wrestlers in the world. Eventually WWE ran out of ideas for both men and now loan them out to overseas promotions to give them something to do.

There have been fewer mass releases and mid-contract cuts without cause since Vince resigned. WWE lets performers’ contracts reach their natural end. Drew Gulak, Donovan Dijak, MVP, Bobby Lashley and Ricochet all became free agents following the expiration of their deals. MVP and Ricochet have already resurfaced in AEW and it looks like a matter of time before Lashley follows.

Releasing talent at a time of record profits, liquidating office staff or whole departments in the wake of WWE’s merger with the UFC may be unfair but it’s not unique.

Corporations seek efficiencies when profitable, to make up for poor performance, when they are acquired or fail. Acquisition by another company is disruptive. Projects continue and workers are laid off regardless of their importance pre-buyout.

Employment in the non-profit/charitable sector is speculative. If the economy slows, donations shrink, leaving a smaller salary pool. Charities may also be subject to the whims of high-ticket donors. If the person who presents the big novelty check seeks a different direction, or wants a position staffed with a friendly agency or otherwise unemployable relative, or they want to become the star of the show themselves, in they go at the expense of current employees.

Pro wrestling often celebrates the worst in people. Nice guys tend to finish last. Would-be promoters who seek to do business differently are derided as “money marks” by fans and wrestlers.

In 2022, SlamWrestling ran a feature on Gordon Scozzari: Unraveling the myths of Gordon Scozzari. Scozzari was a young, avid wrestling fan who came into money and dreamed of making it big. He began promoting shows in 1991 under the AWF banner (one of many promotions to use those letters). He ran a few shows featuring independent, former WWE and international talent. He was taken advantage of by predatory elements within his locker room. The AWF failed and he was ruined.

Scozzari’s shows were beset with no-shows and wrestlers refusing to honor their contracted matches. Rival promoters interfered as well. Scozzari paid significant money for a booker to run back-of house. He kept the money but worked elsewhere, leaving Scozzari to rework his shows with the talent who showed up.

There was no saving Scozzari’s AWF, nor Scozzari himself.

Scozzari was broken financially, and some would say spiritually by his foray into pro wrestling. The title belt he commissioned went missing — it is believed to have been kept by a wrestler who claimed not to have been paid.

One of many troubling parts of Scozzari’s story is the response he received from people within pro wrestling-workers and fans alike. The prevailing attitude within the wrestling community seems to be “If they don’t know how to protect themselves then they deserve it.”

AEW’s Tony Khan is often tagged as a “money mark”. Since opening AEW in 2019 Khan has run his promotion as a viable alternative to WWE. Khan has staked his reputation on being a nice guy by wrestling standards. Current AEW World Champion Jon Moxley called Khan “The opposite of Vince McMahon.” Eddie Kingston said, “I love the man to death and I would do whatever he needs me to do to make sure AEW keeps going.” Former AEW wrestler Jade Cargill praised Khan’s willingness to collaborate on storylines and said Khan “treats [wrestlers] like athletes,” and listening to their needs when it comes to mental health and time off for personal reasons. Nyla Rose has pointed out Khan’s commitment to diversity and representation — a longstanding issue in wrestling. Professional crank Christian Cage states that he wanted to finish his career with AEW since it meant working with Khan.

That said, after exiting AEW amid controversy, CM Punk criticized Khan for being too nice. Appearing on The MMA Hour with Ariel Helwani, Punk said: “He’s not a boss, he’s a nice guy, and I think ultimately that is a detriment to the company but it’s not my company … I’m an outsider. I thought I was brought in to sell merchandise and tickets and draw numbers for pay-per-views and stuff, and I clearly did that, but that’s not what the place was about, and some people didn’t like that.”

The bigger issue is how promoters have prevented wrestlers from accessing post-career benefits like pensions and health insurance through union-busting activities. Jesse “The Body” Ventura attempted to organize the WWE locker room on the eve of WrestleMania 2, only for Hulk Hogan to tattle on Ventura to McMahon. After this effort failed, Ventura started acting in movies. When Ventura returned from shooting, he told McMahon that WWE no longer needed to worry about him. Ventura joined the Screen Actors Guild and has since retired on the pension they provided. In other words, The Body got his. Whether other promoters may have been kinder than Vince McMahon, so far none of them, including Tony Khan, who runs the Jacksonville Jaguars in a unionized environment, would likely be prepared to make this kind of meaningful change.

That’s just business.

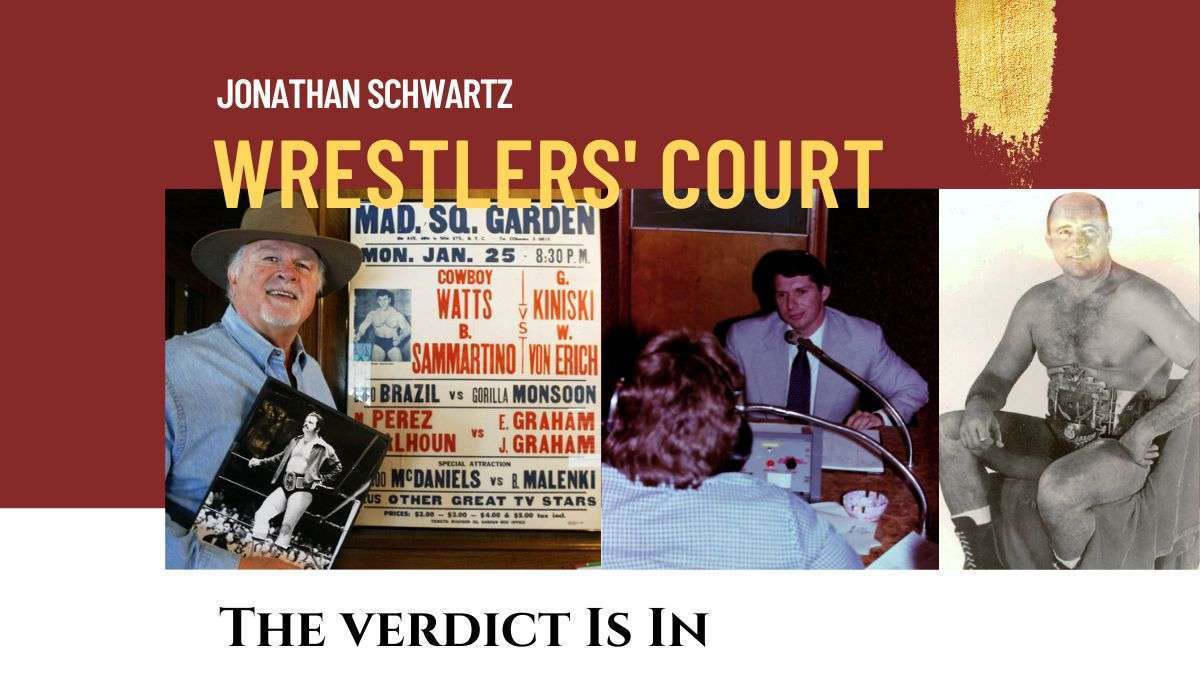

TOP PHOTOS: From left, Bill Watts; Vince McMahon is interviewed, photo by John Arezzi; Verne Gagne.

RELATED LINK