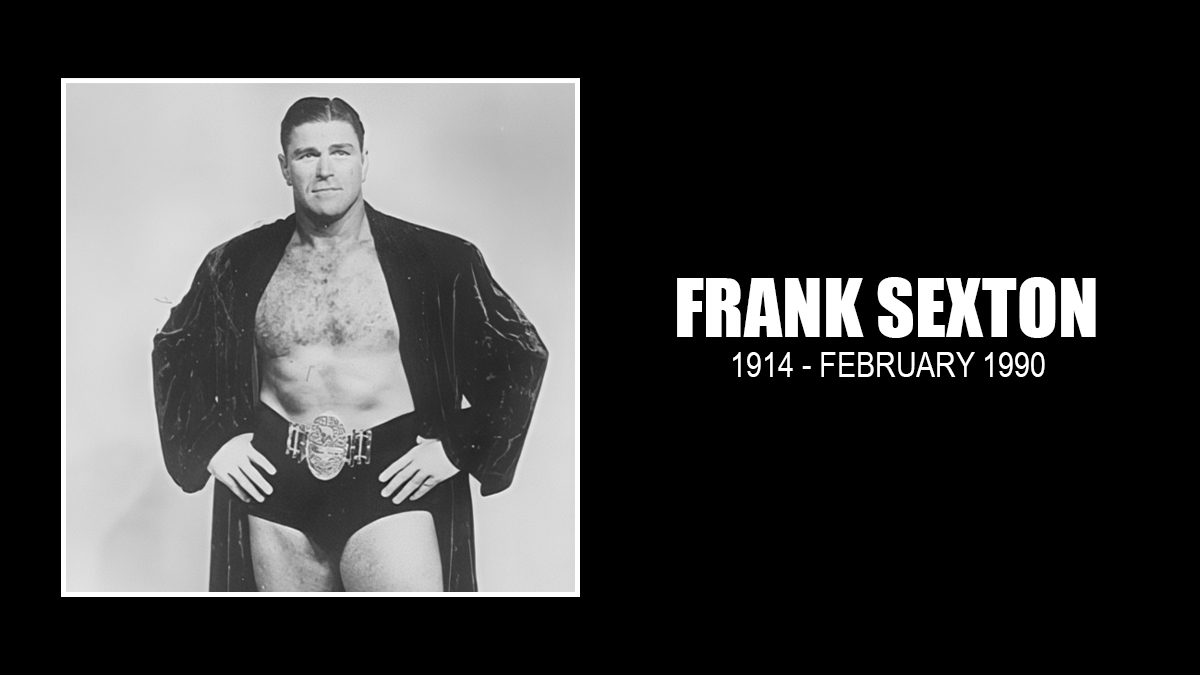

Francis “Frank” Sexton was born in Madison County, Ohio, in 1910 to a large farm family. He earned the nickname “Powerhouse” while playing high school football and the moniker would follow him for the rest of his life.

He attended Ohio State University as a freshman where he played football and wrestled. Sexton left school in 1932 and began pursuing a pro wrestling career. Sexton’s early trainer was Foster “Bull” Gossard, a veteran mat man and former Navy grappler. His early matches were in London, Ohio, on cards that carried both wrestling and boxing bouts. The first recorded bout for Sexton that has surfaced is Dec. 27, 1932. He defeated Tiger Bud Mitchell. After a Jan. 10, 1933 bout at the Armory in London with Bull Smith, a local newspaper described that “Sexton showed much ability as a good clean and smart wrestler,” and added, “Local fans have requested the appearance of Sexton again in the ring.” (Semi Weekly Madison County Democrat, 1/22/33) On Feb. 7, in London, he defeated Chancey Bostick and participated in a six-man battle royal. In the battle royal, the other grapplers, all middleweights, ganged up on Sexton and eliminated him quickly. Former Olympic champion Harry Steel served as the referee. Sexton began appearing in Columbus for Al Haft’s promotion. His Columbus debut was Feb. 15, 1933, where he wrestled to a draw with Karl Davis. Sexton was billed as a “London farmer.”

Powerhouse Frank continued wrestling around Ohio. On Mar. 23, 1933 in Chillicothe, he wrestled to a 20-minute draw with the “Pride of Portsmouth” Pat Mitchell. Mitchell had been a high school football star and the captain of the Washington and Lee wrestling squad. In the same town on July 14, 1933, Sexton faced the rugged football star Roy “Father” Lumpkin. They “battled tooth and nail” to a 45-minute draw. Sexton, labeled a “powerful Sedalia farmer boy,” left the ring bleeding from a badly cut eye. A rematch was held on the next card and this time Lumpkin won taking the 1st and 3rd falls. The third fall was described as “for blood with both going hammer and tongs.” (Chillicothe Gazette, 7/22/33) Lumpkin pinned “the giant farmer boy” after a series of flying tackles and a body slam. Sexton was noted for his use of arm holds during the match.

In April of ’33 Sexton had his first match with Farmer George McLeod in Columbus. The bout was described as “grueling wrestling,” with McLeod having “too much experience” for the big youngster. (Coshocton Tribune, 4/6/34) This was the start of a feud for the Ohio State Heavyweight Title, with the championship passing back and forth between them. McLeod always wrestled in Columbus with his name spelled McCloud. He was a Moravian immigrant raised in Nebraska. His real name was John Ondracek, and he had been a pro since 1920. He had picked up the rough-and-ready catch-as-catch-can style as practiced in the Nebraska and Iowa farm communities. A skilled “shooter” he had served as one of Gus Sonnenberg’s “policemen” during Dynamite Gus’ tumultuous reign as champ. In a Dayton match, they contended not only for the State title but for the “farmer’s championship” as well. Sexton won this encounter, forcing McLeod to submit to a hammerlock. In Dayton, he defeated Ohio State University wrestling kingpin Wilbur “Bill” Renner, using a backdrop and top body hold. On Aug. 16, 1934, again in Dayton, Sexton had his first match with Tigerman John Pesek. The Tigerman, “who probably could have pinned the powerful Sexton whenever he wanted to, wound up the tussle with his pet back slam.” (Dayton Herald, 8/17/34)

Powerhouse Frank began venturing outside of Ohio and appeared in Boston, Wichita, Kansas City, MO, Flint, MI and Colorado Springs. Among his opponents were Orville Brown, the 6’6″ Glen Munn, and Abe Yourist. Sexton continued gaining in reputation, traveling the circuit winning and losing bouts. In early 1939 he donned a mask for the first time and was billed as the Masked Marvel. On February 21st, he lost a bout to John Pesek, the current MWA titleholder in Cleveland. A month later he lost to Jack Washburn and was unmasked. Heading to the West Coast, he won the Pacific Coast title from Wild Bill Longson in San Francisco Aug. 25, 1940. The next year, 1941 found Sexton back under a hood as the Black Panther, wrestling in Northern California. His manager was the erstwhile Count Pietro Rossi. Count Rossi was a pioneer “heel” manager and specialized in handling hulking masked men. As the Black Panther, he regained the Pacific Coast belt, beating Bobby Managoff in Oakland. Jim Casey took the title and his mask from him in Frisco on Mar. 21, 1941. Masked or unmasked, Sexton established himself as a West Coast mat star. Through March and April of ’42 he was barnstorming around the country, hitting Missouri, Kentucky, Nebraska, West Virginia, and his home state of Ohio.

Sexton was scheduled to wrestle Rube Wright, “The Preacher’s Son” on May 28, 1942 in Fresno but proved to be a “no show.” Wright had a reputation as a tough mat man and was considered the “club champion” of Southern California. He was feared as an independent maverick who didn’t always follow the promoters’ bidding. In April of 1942, the California State Athletic Commission had dethroned Jimmy Londos, removing their recognition of him as the world heavyweight wrestling champion. L.A. promoter Ray Fabiani was quickly on the scene to announce a tourney to replace him and crown a new king. Tournament matches were held on the weekly Olympic cards and a veritable who’s who of the current mat stars took part, including Danno O’Mahoney, Ali Baba, Vincent Lopez, Iron Mike Mazurki, Jumping Joe Savoldi and the old war-horse Ed “Strangler” Lewis, in addition to Fabiani’s “big three” Sandor Szabo, Rube Wright and Pat Kelley. Latter reports noted that, “Londos had refused to meet Rube Wright, who was king of the outlying clubs, and had been chasing ‘Jeemy’ all over the place demanding a showdown.” (Los Angeles Daily News, 8/19/42) Another sports writer commented, “Wright is really responsible for the tourney, as he was the man who forced Londos’ hand and caused him to run…” (Los Angeles Times, 8/19/42) A couple months into the tourney, San Francisco promoter Joe Malcewicz entered his top man “Powerhouse” Frank Sexton. The irrepressible Jack Pfefer showed up with the Swedish Angel (Phil Olafsson) and Karol Krauser and declared that they would “force their way into the tourney.”

Sexton was shaping up as the favorite to win the tourney. Wright returned to the tourney for the first time since late May on July 22nd and knocked Kelley out of the competition. The following week Wright defeated Szabo, Sexton beat George Zaharias, and Lewis won over Krauser. Zaharias and Krauser were eliminated. Karl Pojello with the French Angel (Maurice Tillet) in tow, arrived on the scene and threatened to chase the Swede version of the “angel” gimmick out of L.A. It was too late for the French Angel to enter the tourney but Fabiani booked him for some non-tournament matches. Pojello’s Angel debuted on August 5th and defeated Rube’s brother Kolo Stasiak (Jim Wright). On the same card, in a tournament contest, Szabo beat Wright with a leg-strangle. The loss didn’t put Wright out of the competition, as the rules stated that a wrestler remained in the running until he had lost two matches to a seeded opponent.

They were rematched on the next card, and this time, Wright proved the victor, vanquishing Szabo with his pet maneuver, the step-over toe hold. The tournament was down to three finalists — Wright, Sexton and the Swedish Angel. Wright and Sexton were scheduled to square off on August 19th, the 19th week of Fabiani’s tournament. Sexton ducked out without any notice or explanation. In response his wrestling license was revoked by the state commission. Did Sexton fear that Wright would “shoot” on him? Fabiani, apparently perplexed, was ready to cancel the whole shebang. His associates Toots Mondt and Nick Lutze convinced Fabiani to bring it to a conclusion and to go ahead and pit Wright and Pfefer’s Angel as the final bout with the winner to be proclaimed the world heavyweight champ. Wright was certainly not Fabiani’s top choice to be the champ.

Wright and the Swedish Angel met for the title and belt on August 19 with no less a personage than Bull Montana handling the referee chores. 9,500 fans were on hand to witness the crowning of a new mat king. A total of 51 wrestlers had participated in the tournament and it was now down to the last two men standing. It proved to be a rough, grueling battle. At the 41:30 mark, Pfefer threw in the towel as his man writhed in agony from Wright’s step-over toe hold. Olafsson suffered an injury and was unable to continue. He forfeited the second fall and thus the match to Wright.

An in-ring ceremony was held and CSAC commissioner Everett Sanders presented Wright with the trophy diamond belt and he was announced as the new world heavyweight wrestling champion. Wright shared that designation with four compatriots: Wild Bill Longson (National Wrestling Association), Roy Dunn (National Wrestling Alliance-Kansas), Steve “Crusher” Casey (American Wrestling Association-Boston), and Orville Brown (Mid-West Wrestling Association).

Sexton had found his way across country, wrestling in Rochester and Toronto. For his part, Wright defended his title around Southern California briefly, but plans were underway by the “powers that be” to weed him out and bring Londos back. His “world title” was reduced to a “California state title.” Determined to make hay while the sun was shining, Wright accompanied Pfefer’s merry band when they returned east. Under Pfefer, Wright made appearances from Washington DC for Joe Turner up into New England, billed as the world champ. Londos was back in southern California by November of 1942, and, as if he never left, enjoyed the billing of “world heavyweight champion.”

In 1943 both Sexton and Wright returned to Los Angeles. The latter seemed content to accept his role as the state titleholder. Sexton was ballyhooed as “the uncrowned wrestling champion of the world.” A series of matches between the two bruisers was held, resulting in Sexton taking the state crown. Sexton had rivalries with Dean Detton and Szabo. They represented different claims to the California heavyweight championship. Detton and Sazbo’s claims were based in Northern California and called the Pacific Coast championship. Sexton’s was based in LA and was generally referred to as the California State title.

Sexton wrestled to a draw with “world champion” Londos in LA on Dec. 8, 1943. The match was held as a war find benefit/joint Ray Fabiani/Hugh Nichols promotion at the Olympic Auditorium. Powerhouse Frank was billed as “the number 1 contender.” The bout was described as a “scientific struggle” with “Old Jim… too smart for his foe.” (Los Angeles Times, 12/9/43) A few nights later Sexton defeated Wright again at the Pasadena Arena. A sportswriter commented, “Sexton has shown the kind of stuff that has made old-timers compare him with Frank Gotch.” (Monrovia News-Post, 12/11/43)

By the end of the year, Sexton left behind his West Coast laurels and hit the Northeast. He was recruited by upstate New York promoter Ignacio “Pedro” Martinez and became a box-office star on cards in Rochester, Buffalo, and Toronto. He debuted in Rochester on Dec. 29, 1943, taking on John Katan. Martinez handled the promotional end of the game in Rochester at the time, while still appearing as a wrestler in Buffalo and Toronto. He was Sexton’s opponent in the latter city on Feb. 23, 1944. Sexton shot to the top in the territory, facing Whipper Billy Watson, Bobby Managoff, Ed “Strangler” Lewis and Earl McCready.

On May 10, 1944, in Rochester, he met the National Wrestling Association champ Wild Bill Longson. With one fall each, the bout was stopped by curfew and Sexton was awarded the referee’s decision. Longson protested and Martinez stepped in and ruled that a title couldn’t change hands on a decision. The antagonists were given an additional ten minutes, but no falls were registered and the match was called a draw. Yvon Robert, the great French-Canadian wrestler and protégé of Emil Maupas, held the Montreal version of the world heavyweight. He initially refused to wrestle Sexton. When threatened with suspension, Robert agreed to defend his crown against Powerhouse Frank. On July 19, 1944, Sexton won over Robert in Montreal and annexed his title. A month later, Robert reclaimed his championship.

January 1945 found Sexton wrestling in Boston for promoter Paul Bowser, knocking off Rebel Bob Russell and Ed “Strangler” White among others. In Rochester, he held AWA titleholder Steve Casey to a draw and lost in a rematch. Back in Beantown, Sexton had similar results in a bout with “duration AWA champion” Sandor Szabo. Casey beat Szabo in Boston on Apr. 4, 1945 with baseball legend Babe Ruth as the referee. The title claim passed back and forth between Casey, Szabo and Sexton. (1.) On June 27, 1945, in Boston, Sexton defeated Casey and won national recognition as the world heavyweight champion. Powerhouse Frank challenged to take on “anyone, anytime, anywhere on a winner-take-all basis with his title on the line.” As historian Steve Yohe commented, “No wrestler showed more willingness to meet his rival claimants than Sexton.” Sexton held this championship title for almost five years. Some consider this the most legit heavyweight championship lineage existing at the time.

On Jan. 10, 1946 in Toronto, Sexton squared off against NWA champ Wild Bill Longson and battled to a 58-minute curfew draw. This was promoter Frank Tunney‘s debut card. On the 29th of the same month Sexton went to Baltimore, MD to face rival champ Babe Sharkey. He beat Sharkey and had now amalgamated two heavyweight titles.

The Maryland State Athletic Commission had removed their recognition of Jimmy Londos as the world heavyweight king for failing to defend it. Bobby Stewart, the Golden Terror, claimed that he was responsible for chasing Londos out of Baltimore. A 16-man one-night tourney was held at the Coliseum in Charm City on Mar. 7, 1944, with the winner to meet Ed “Strangler” Lewis for the championship. Sharkey triumphed over three opponents, defeating Leo Wallick in the final bout. Other competitors included John Bonica, Hans Kampfer, Michele Leone and local favorite Nick Campofreda. Lewis and Sharkey squared off on the next Coliseum card. “Sharkey, relying on his youthfulness, played the cautious role, and forsook his usual aggressive style to wear down the veteran in the half-hour-long match… the Babe back-pedaling from his foe.” (Baltimore Evening Sun, 3/15/44) He finally dropped the Strangler with a gut-punch and pinned him. Sharkey’s title claim was touted in other eastern states and he defended it until losing to Sexton.

In 1946, Sexton faced Paul Bowser’s latest Irish sensation and hammer throw champion, Bert Healion, in Wilmington, DE, Baltimore, DC, and Boston, successfully defending his championship. Healion received a heavy “push” and counted Babe Sharkey among his victims. Back on the west coast, Sexton faced rival title claimants Sandor Szabo, Enrique Torres, and Lou Thesz, all resulting in draws. In Cleveland, Ohio, on November 30, 1948, another title unification match was held with Cliff Gustafson. Gustafson had a stellar amateur mat background. He had been the captain of the University of Minnesota wrestling team, an All-American, an NCAA, AAU and Big Ten champ. Gustafson was part of the team of American amateur grapplers that barnstormed Europe in 1938 and he was then recruited by Tony Stecher into the pro ranks. Early on, he was handled by Billy Sandow and later by Ed “Strangler” Lewis. Cliff was a highly skilled grappler, and like Sexton, he was big and powerful. They wrestled for sixty minutes with no falls; Frank was awarded a decision.

The pair of powerhouses were booked for a rematch by Stecher at the Auditorium in Minneapolis on Dec. 21, 1948. A sports writer commented, “The issue is: Who is the real heavyweight wrestling champion?… at least four matmen claim the honor. Two of the four are Frank Sexton, of Sedalia, Ohio, eastern titleholder, Cliff Gustafson of Gonvick, Minn., Upper Midwest kingpin. They’ll tangle in the main event…The other two are Orville Brown of Wallace, Kan., and Lou Thesz of St. Louis.” (Minneapolis Star-Tribune, 12/19/48) Stecher appointed wrestler Johnny Marrs to serve as the referee. The rival champs wrestled to a 60-minute draw. A brawl broke out twice between Sexton and Marrs during the bout.

Sexton was back in Baltimore on January 25, 1949, to wrestle former University of Iowa wrestler and AAU and Big Ten champ Wilbur Nead. Baltimore Sun sports editor reported that it was rumored to be a “shooting match.” The bout went on to a 50-minute draw, stopping at the 11:30 p.m. curfew. The local newspaper described, “It was refreshing to watch two heavyweights compete minus the usual horseplay and hokum. ” (Baltimore Sun, 1/26/49)

Yet another “unification match” saw Sexton battle Orville Brown in Cleveland Mar. 15, 1949. Ex-boxing champ Jack Sharkey was the special referee. The bout went to a one-hour 45-minute draw; no surprise. Publisher, writer, and combat sports authority Stanley Weston stated, “Frank Sexton in our opinion is the finest wrestler in the world. Others who may be listed in Frank’s class are Wilbur Nead, Ruffy Silverstein, Orville Brown and Louis Thesz. If an honest to goodness elimination were held, we feel certain that these would be the men to come out on top.” (Ring Magazine, Jan. 1950)

Looking for new fields to conquer, Sexton traveled across the ocean to Europe to defend his title in early 1950. He defeated Ivar Martinson, Henri Deglane and Felix Miquet among others and wrestled to a draw with the notoriously tough Bert Assirati. Credit must be given to Sexton for that last match, as facing the Anglo-Italian Assirati was something that many wrestlers declined to do.

Returning stateside, Sexton was touted for his triumphant international tour. His first match back in America was in Boston versus “Mr. America” Gene Stanlee. Sexton was described as the “last of the old-line wrestlers” (Boston Globe, 4/27/50). With one fall apiece, they broke into fisticuffs and crashed out of the ring. They continued brawling outside the ropes and when the referee counted to twenty, the match was stopped and ruled a draw. Sexton headed to his home turf of Ohio. A changing of the guard was in the works. Powerhouse Frank had worn the AWA crown for nearly five years.

On May 23, 1950, Sexton was matched with popular Mohawk Indian star Don Eagle in Cleveland by promoter Jack Ganson. He advertised it as a “shooting match” with a reported $5,000 purse up for grabs to be split 70-30% winner-loser. Each wrestler was said to have put up a $2,500 forfeit to guarantee their appearance. The referee’s identity would not be revealed until the time of the match. The local athletic commission announced that “the match will be conducted without any dramatics or phony tactics.” (Mansfield News-Journal, 5/23/50)

Don Eagle defeated Sexton for the second and third falls and was awarded the championship. Sexton later claimed, “I got a fast count from the referee Freddy Weidermann… Don Eagle caught me in a reverse back slam. As soon as my back hit the mat I went into a ‘bridge.’ I was ‘bridged’ when Weidermann counted me out.” (Boston Globe, 6/27/50) Eagle’s reign was over almost before it got started, falling victim to a Chicago promotional war between Fred Kohler and Leonard Schwartz. The new champ was scheduled to take on Gorgeous George at the International Amphitheater in the Windy City on May 26th. Kohler apparently arranged for George and referee Earl Mollahan to pull a double-cross on the Mohawk.

Despite his outlandishness and showmanship, Gorgeous George was actually a fairly capable wrestler. He had grown up as a tough street kid on the Houston waterfront and had been wrestling for money since he was a teenager. Eagle won the opening fall by submission with the Indian Death Lock. Thrown out of the ring, he was counted out to lose the 2nd. The “dirty deed” was done in the third, when George had Eagle down on the mat. He kicked out, but the referee called it a pin and declared Gorgeous George the victor. Eagle erupted in a fury and attacked the ref, punching him and chasing him out the ring. The crowd was incensed and George had to fight his own way to the dressing room. This match is one of the most controversial bouts of that era. Gorgeous George lost to Lou Thesz in Chicago on July 27th, and Eagle won a rematch over the “Human Orchard” on August 30th. Eagle continued to get some billing as the champion but as Steve Yohe wrote, “the damage remained permanent. The AWA title would live on until 1953, but without a champion like Sexton, its prestige was never the same.”

Paul Bowser booked a Sexton/Eagle rematch in Boston on June 22, 1950, with the Indian billed as the defending champion. It went to a one-hour time limit draw, one fall apiece. Steve Passas was the referee. The judges rendered a split decision: Fred Meyer for Eagle and Leon Burbank for Sexton. By the beginning of the new year, Sexton was off on another European tour, where he would be billed as “the world champion.” International tours would mark the last several years of Sexton’s mat career, with the Powerhouse wrestling in Europe and Africa. On January 22, 1951, he lost a “championship” match to Felix Miquet in Paris. This appears to have been the last loss on his record. On that tour in Gent, Belgium, he defeated Karel Istaz, aka Karl Gotch. In South Africa, he had numerous bouts versus Willie Libenberg and Ken Schishka. By the summer, he was back wrestling in North America, and in October, Sexton wrestled in Havana, Cuba.

The year 1952 found him on another European and African tour, highlighted by a series of matches with Primo Carnera. Back in America in May, one of his big matches was a victory over Quebec strongman Adrien Baillargeon in Washington, DC. He made yet another European tour in 1954 and continued wrestling around Ohio and New England. In March of 1956, in Rochester, NY, Sexton defeated Roy McClarity by disqualification. He was described as “the aging mat master” and as “the wrestler of a thousand holds.” McClarity had Sexton against the ropes and refused to break, so the ref called an end to the bout. The fans booed the decision. The next night, he was in Buffalo, where he beat Hard-Boiled Haggerty. His active mat days were winding down.

The next summer, Buffalo promoter Pedro Martinez brought Sexton east to the main event a card as part of the Monroe County Fair. He was matched with the powerful Yukon Eric. To explain Sexton’s absence in local rings, Martinez concocted a tall tale that he’d been busy with a triumphal tour of Japan and Australia. Complete ballyhoo. As best as research indicates, Powerhouse Frank never set foot in Japan or Down Under. Sexton added the name of Yukon Eric to his win column.

Martinez recruited Sexton yet again to appear in Buffalo for the final match of his career. He agreed to take on another behemoth, Big Moose Cholak, all 350 pounds of him. The bout was set for March 5, 1965. Sexton, 53 years old and “deeply tanned,” told the press, “I keep in good condition by doing manual labor in my own contracting business and wrestle about twice a week.” Powerful Frank tossed his massive opponent in 14 minutes.

Steve Yohe summed up his thoughts on Sexton, writing, “The general consensus among those that saw him or worked with him was that he was a fine worker and a class act. He was a major box office attraction in every area that he wrestled in, which would include New England, Northern and Southern California, Cleveland, Buffalo, St. Louis, Montreal, Toronto, and Paris. His world title reign remains one of the greatest in pro wrestling history as he met every major performer and rival champion and held enough stature and respect with them and promoters across the country that he came through all of the matches with his title still comfortably around his waist. The respect he had in the profession was shown by the fact that while he was never double-crossed during his five-year reign, his successor was allegedly double-crossed for the title only four days after winning the belt. Among the world champions of the immediate post-war era, Sexton had a career that could have only been eclipsed by the rise of a Lou Thesz.”

Sportswriter Sid Feller recalled in reference to Sexton, “There is no fuss or fanfare about Frank Sexton when he goes into action. Frank is strictly business from top to bottom, a master craftsman who enjoys his work.”

Powerhouse Frank Sexton wore his championship belts proudly and represented the sport with integrity. With the exception of him unexpectedly dropping out of Fabiani’s LA tourney, there was never a hint of Sexton ever ducking anyone. He met ’em all, from Tigerman John Pesek to Lou Thesz to Bert Assirati to Karl Gotch.

Sexton died in February 1990.

FOOTNOTES

- “On May 21, 1945 Frank Sexton pinned old rival Sandor Szabo to win the AWA World Title at Buffalo, NY. The line of the AWA World Title traced back into the main line of the World Title first through Henri Deglane’s controversial May 4, 1931 win over Ed Lewis, and later through Lou Thesz’s loss to Steve Casey in Boston on Feb. 11, 1938, that ended Thesz’s first world title reign. Many people, not only those who lived in New England but also those who believed that title should be won and lost in the ring, considered the AWA World Title as the legitimate World Title over Bill Longson’s National Wrestling Association Title and Jim Londos’ long-standing world title claim. The title also had the prestige of the belt worn by Ed ‘Stranger’ Lewis in the early 1920’s. Two weeks after winning the title, Sexton dropped the title to Steve Casey…The two would be rematched on June 27, 1945… Sexton regained the title from Casey. This time Sexton would hold the belt almost five years straight, one of the longest title major world title reigns in pro wrestling history.” -Steve Yohe

NOTE: Quotes from Steve Yohe in this article are from a biographical piece he wrote with John Williams. Steve graciously shared both the bio and a Sexton ring record that were of great use in researching this article.