There is a classic bronze sculpture of the head of a professional wrestler in the Harvard Art Museums. It is not of Hulk Hogan or Dwayne Johnson, or of Danno O’Mahoney or Steve Casey, the Irish immigrants who settled in Boston and became heavyweight champions of the world.

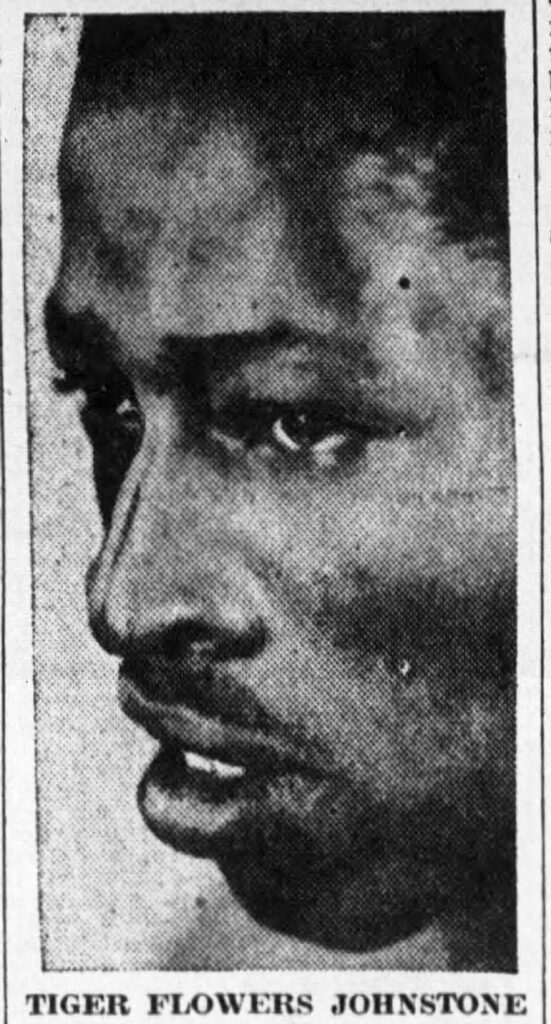

Instead, the well-exhibited bust is of little-known Charley “Tiger Flowers” Johnstone, one of the first Black wrestlers to appear in Northeastern rings, the first to be featured there regularly, and the first to have his main-event match disrupted by the Ku Klux Klan.

It happened on June 30, 1934, when the matchmaker Jack Pfefer, Johnstone’s patron, pulled him from a card in Teterboro, New Jersey. The day before, Pfefer and partner Jack Johnson received a threat marked from the “K.K.K.”

“Guess you haven’t been reading the Bergen County newspapers lately else we don’t think you would have the nerve to bring Tiger Flowers Johnstone over to wrestle at Teterboro Saturday night,” the note said. “We still have a few more crosses to burn and we never run out of matches. This is just a friendly tip, so take it while the taking is good and call off the match.”

“Guess you haven’t been reading the Bergen County newspapers lately else we don’t think you would have the nerve to bring Tiger Flowers Johnstone over to wrestle at Teterboro Saturday night,” the note said. “We still have a few more crosses to burn and we never run out of matches. This is just a friendly tip, so take it while the taking is good and call off the match.”

Police investigated the alleged Klan activity to no avail while Pfefer substituted Max Martin for Johnstone. As Romeo L. Dougherty of the New York Amsterdam News concluded of the incident: “Things have not been so good for the colored boys who engage in the sport of professional wrestling.”

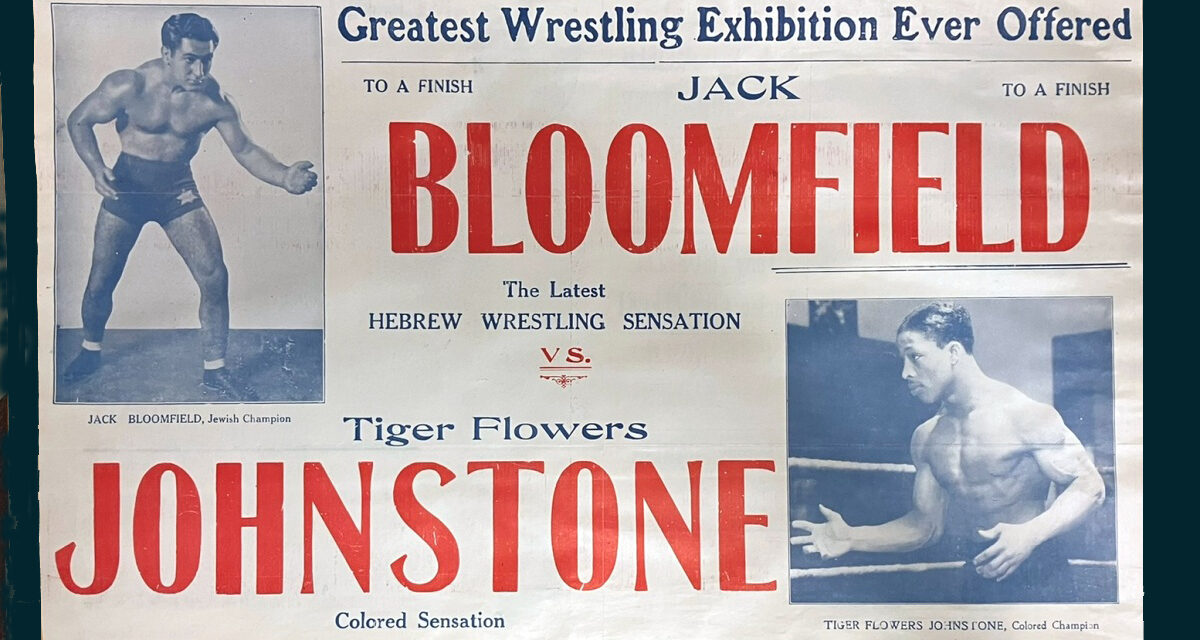

Johnstone, who wrestled several hundred matches from the mid-to late-1930s, was a popular, reliable performer against white wrestlers at a time when mixed-race matches were barred in many parts of the country. But history books have overlooked him and it’s easy to understand why.

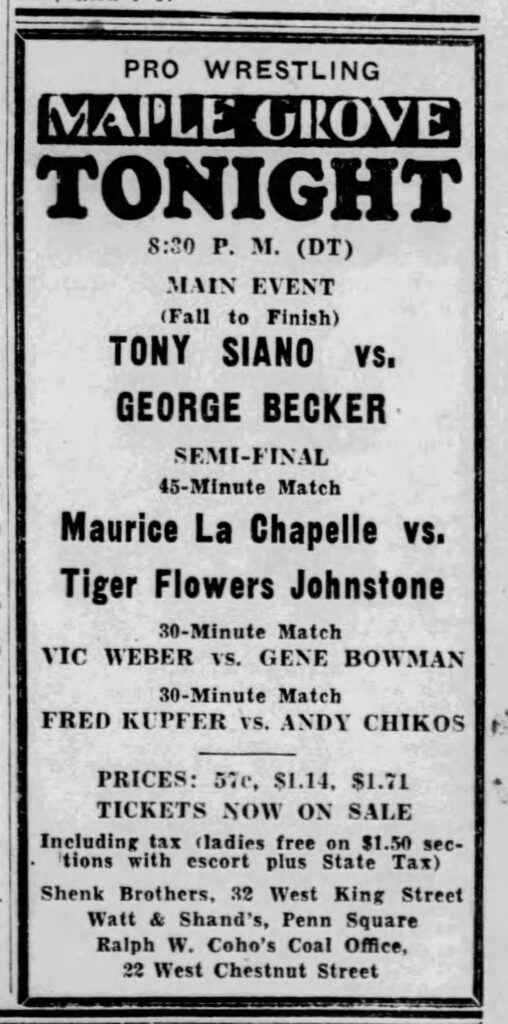

Though billed informally as “colored champion,” he was not a headliner, working mostly on undercards, often against Maurice La Chappelle, his chief rival for years. He never held a title belt and battled almost exclusively against light-heavyweights at a time when heavyweights reigned supreme. Johnstone also faced a built-in booking bias because he was part of the troupe of Pfefer, the eccentric agent and promoter who was an outcast to the wrestling establishment.

But the most telling factor was his heritage; in fact, the U.S. citizen Johnstone was billed as a “Cuban negro,” like Jack Claybourne, an early Black star who wrestled as Latino Pablo Hernandez because his skin color held him back. “It is the same old story of America drawing the color line on her own citizens, but gladly welcoming what they believe to be foreigners,” Dougherty wrote.

Not much is known about Johnstone’s early life. He appeared on the mat at the same time in the winter of 1933-34 as a group of national promoters, frustrated with Pfefer’s business dealings, cut him out of a lucrative syndicate deal and limited him to running shows in smaller venues in New York. Johnstone had reportedly done some boxing, though there is no record of him fighting under that name and it was just like Pfefer to take an unknown fellow off the street and turn him into a pro wrestler and moneymaker, mostly for himself.

“I knew he was a great wrestler but you can believe me when I say that I never saw a man who has developed to such a degree in his particular business as the black panther. He’s a wonder,” Pfefer said.

Pfefer ritually repackaged his talent and quickly introduced ambiguity, deceit or both into his new wrestler. Theodore “Tiger” Flowers was a prominent boxer who became the first Black middleweight champion in 1926 when he defeated Henry Greb. “The Georgia Deacon” died a year later of complications from surgery and an estimated 75,000 mourners passed by his casket in Atlanta.

Fast forward seven years and boxer Flowers was still in the minds of fans of the combat arts when Pfefer expropriated his identity for his “Tiger Flowers” Johnstone.

The manager never claimed a direct relationship between Flowers and Johnstone, but the implication was unmistakable, especially when Boxing News hailed Johnstone as the greatest attraction since Jack Johnson, the legendary Black heavyweight boxing champion.

“One of the grandest characters in the world, this lean 175-pound race horse, whose every move is like the picture of a race horse burning up the track, is conceded to be one of the outstanding and most formidable performers of his weight in the world,” Boxing News said of Johnstone in 1934.

Johnstone impressed right away, wrestling at peak two or three nights a week at Jamaica Arena, St. Nicholas Arena and Broadway Arena for $10 a shot, according to Pfefer’s business ledgers at the University of Notre Dame. His first recorded match was in January 1934 and he fought La Chappelle, a Hungarian who Pfefer turned into a French champion, three times that month and at least 33 times during his career. It was enough for New York sportswriter J.J. McAlester to dub Johnstone as La Chappelle’s “perennial rival.”

Johnstone impressed right away, wrestling at peak two or three nights a week at Jamaica Arena, St. Nicholas Arena and Broadway Arena for $10 a shot, according to Pfefer’s business ledgers at the University of Notre Dame. His first recorded match was in January 1934 and he fought La Chappelle, a Hungarian who Pfefer turned into a French champion, three times that month and at least 33 times during his career. It was enough for New York sportswriter J.J. McAlester to dub Johnstone as La Chappelle’s “perennial rival.”

His arsenal did not rely on a single finisher; Johnstone employed all the standard holds of the day — arm locks, scissors, half- and full-Nelsons. But he put them together in a style that was pleasing to the eye. The Bergen (N.J.) Evening Record identified him as “one of the most supple, scientific grapplers of the present age. He is spry as a panther and just as foxy.”

Johnstone understood the value of showmanship, as well. In a 1934 bout against Curley Donchin in Babylon, New York, the two went after each other with flying tackle after flying tackle until they knocked each other senseless, fell to the mat and were both counted out.

He seldom ventured from the Northeast area, though he briefly toured Michigan in 1935, wrestling Ralph Garibaldi and Freddie Knichels in Benton Harbor, later home to Black star Bobo Brazil.

There is no official “Tiger Flowers” Johnstone Record Book, but the popular WrestlingData.com site suggests his results were pretty evenly split between wins, losses and draws from 1934 to 1939. His biggest name opponents were Dave Levin, a Pfefer find and future world champion, Carolinas legend George Becker and a young “Bull” Curry, who topped Johnstone in 1936 in New York.

His biggest win, coincidentally, came with a boxer in the ring. Jack Dempsey was the special referee for a mini-battle royal in December 1938 at Boston Arena. At that point, the Johnstone name had largely fallen by the promotional wayside. “Tiger” Flowers took the event against Jack Singer, the Syrian Kid and a rough-and-tumble masked wrestler named Dark Hazard. Flowers stopped Hazard in 13 minutes at which point Dempsey tore off the hood to reveal “Bull” Curry.

Johnstone’s active career petered out around 1940, though more ripoffs of the “Tiger” Flowers name kept fans guessing. A “Tiger” Flowers wrestled in New England in the mid-1940s, but he was billed at 225 pounds or about 30 percent heavier than Johnstone. Hilliard Fann boxed in the 1940s as “Young Tiger” Flowers because his southpaw ring style mimicked the original prizefighting champion.

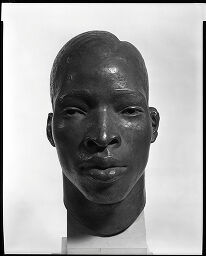

Bust of Tiger Flowers Johnstone. Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College

His post-wrestling life remains unearthed, and the story behind the wrestler’s sculpture is just as much of a puzzle to historians. The noted artist Emily Winthrop Miles created the art piece, initially entitled “Wrestler/Head of a Negro,” in 1934. Miles fashioned sculptures of athletes and dancers, and also made drawings of Johnstone and his wife.

The bust is 13 1/2 x 8 x 10 3/4 inches, was bequeathed to the Fogg Museum at Harvard by Miles’ father and has been on display at museums and art centers. The connection between a renowned sculptor and one of Jack Pfefer’s handymen has never been established, though. Curators at the Fogg Museum and the Springfield, Massachusetts, Museum of Fine Arts, where the sculpture once resided, suspected Miles somehow knew the Johnstones in New York.

But 90 years after the Ku Klux Klan tried to run Johnstone out of the wrestling business, his legacy endures. As Lee Sheridan of the Springfield Daily News observed, “The bronze head of Tiger Flowers Johnstone, however, stands in the Museum of Fine Arts as a powerful tribute to the sculptured beauty of his race as seen by the unprejudiced eye of a white artist.”