At the beginning of my journey as a wrestling historian back in 2013, I turned to eBay to search for clues to the storied past of professional wrestling in Louisville, Kentucky. One of my first finds remains one of my favorites: a 1953 program featuring Baron Leone and The Great Zorro on the cover. Held at The Armory, now known as Louisville Gardens, the show was a benefit for the Louisville Police Widows and Orphan’s fund, and in the 1950s, it was the biggest wrestling event of the year for the Allen Athletic Club. The program cost me $20, plus some shipping.

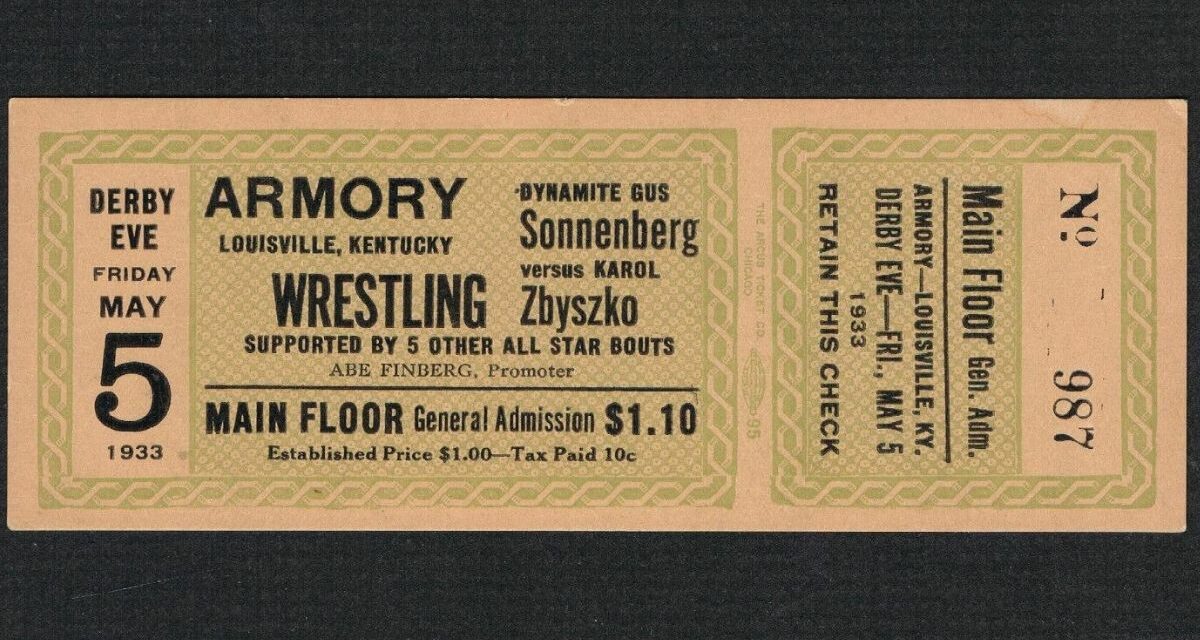

At the same time I found the program, I spotted an item with a much higher price tag: a ticket for a wrestling card at The Armory on May 5, 1933, the night before the Kentucky Derby. The ticket included name of the promoter, Abe Finberg, and the two stars in the main event: Karol Zbyszko and Gus Sonnenberg. The price of admission was a mere $1.10, but the asking price on the eBay listing was $350. I didn’t buy the ticket, but I bookmarked the listing, intending to research this particular event and include it in my book, Bluegrass Brawlers: The Story of Professional Wrestling in Louisville.

My first dive into the Louisville Courier-Journal newspaper archives took place among the metal filing cabinets filled with microfilms at the downtown branch of the Louisville Free Public Library. I didn’t get to every month and year because I simply didn’t have the time. I had a 40 hour a week job, and I had a family. But I made sure to look closely at the May 1933 records, searching for the results from the Derby Eve show.

That initial search came up empty. There was no mention of the show on May 5. There were no results posted May 6. And backing up to April, there was no ad in the Sunday newspaper either.

My first conclusion was that the ticket was a fake. If no show took place, how and why did this ticket ever come to be? And who, in their right minds, would fake such a thing?

It took a deeper dive into the past to discover the whole truth. Thanks to newspapers.com, the Louisville Courier-Journal archives are now online and much easier to navigate. I pulled every weekly result from 1935 to 1957 while writing a book about the Allen Athletic Club. Then in the fall of 2021, I pulled every result from 1900 to 1967 (when Dick the Bruiser left town and Louisville went dark) while revising my first book, Bluegrass Brawlers. And that was when I found the rest of the story.

The show described on the mystery ticket was announced in the papers. Tickets were put up for sale. The ticket may in fact be real, but the show itself never took place.

So what happened?

It turns out the ticket on eBay is part of a much larger story. In 1933, the hottest wrestling promotion in town was at the Savoy Theater, a vaudeville house that presented wrestling every Thursday. Cincinnatus B. Blake presided over all the entertainments that appeared at the Savoy while the wrestling shows were managed by a referee turned booker named Heywood Allen. Allen joined the Savoy in 1930, and the promotion’s popularity grew immensely with his arrival. But while a host of welterweight grapplers waged war inside the Savoy’s ring, Blake and Allen were staging their own fight against an institution dubiously named the State Board of Athletic Control.

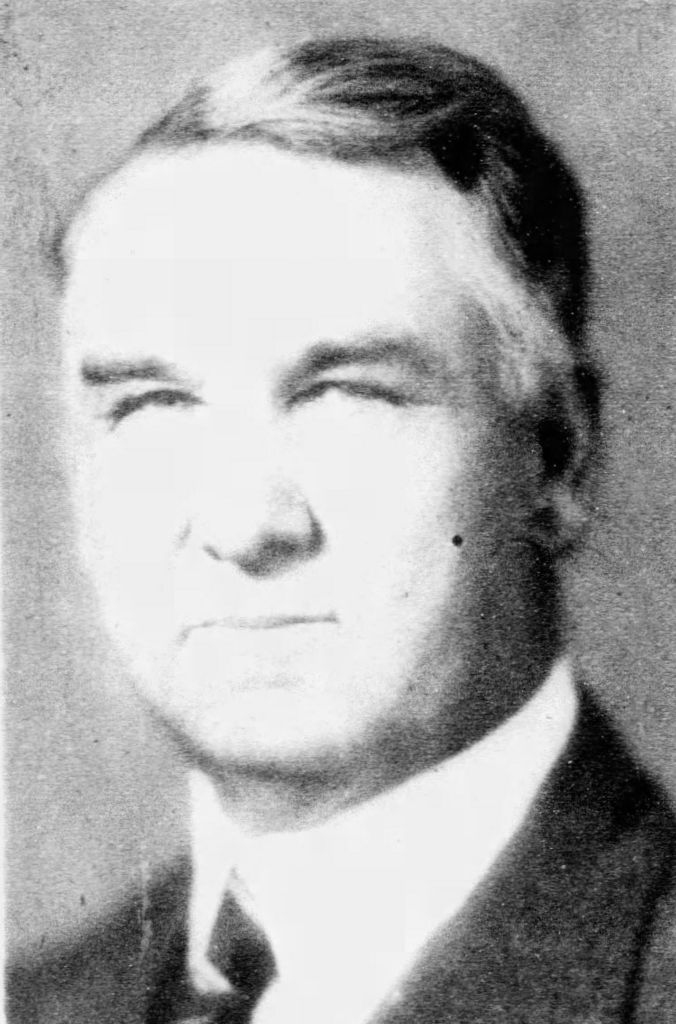

Heywood Allen

The Board came into being back in 1920 with the express purpose of regulating fight sports in the state of Kentucky. The bill that created the Board spelled out certain fees that the Board would collect from promoters and promotions of boxing, but the same fees were not required for wrestling shows. Wrestling was not as big in Kentucky as boxing at the time, so the authors of the bill left wrestling outside the Board’s jurisdiction so as to not quash its potential growth.

As the 1920s roared along, wrestling finally started to come into its own in Kentucky. The downtown theaters began featuring wrestlers on a weekly basis, and In 1928, an amendment to the law was passed intended to rope wrestling promotions under the watchful eye of the State Board of Athletic Control.

After so many years of being able to keep all the profits at the gate, promoters like Blake rankled at having their pockets picked by a Board made up of political appointees. By the summer of 1931 Blake decided he’d had enough. Blake took a stand by refusing to renew his license with the State Board of Athletic Control. He and Heywood Allen immediately announced they would continue running shows without the permission or oversight of the State Board.

Cincinnatus B. Blake

The Board took swift action and attempted to shut Blake down, but when the case went to court, Judge John Marshall sided with Blake. The language in the 1928 bill proved to be the sticking point. The amendment said that the Board would govern “sparring and boxing” in the state of Kentucky. The Board said wrestling fell under the definition of sparring. Blake disagreed, and so did the judge, who permitted Blake and Allen to proceed with their unlicensed wrestling shows.

Wrestling resumed at the Savoy, and the fans continued to turn out week after week. Unable to shut down the Savoy by legal means, the Board began granting licenses to new wrestling promoters, hoping to find someone that might run the Savoy out of business. One by one, the new promotions were announced. One by one they failed.

Near the end of 1932, the Board granted a license to the Olympic Athletic Club, a wrestling promotion founded by one Abe Finberg. Finberg was no stranger to wrestling or the Savoy. Just a few years before, he had run wrestling exhibitions on Friday nights a few blocks from the Savoy at the burlesque theater known as the Gayety. Wrestling at the Gayety went away not because of lack of interest but more because of politics. The Gayety was a frequent target of moral crusaders who objected to the “indecent” productions hosted at the theater — even though other theaters, frequented by the upper crust of Louisville society, put on shows that were much more lewd in content.

The Savoy had built its reputation by showcasing the best welterweight grapplers in the region. Fans packed the theater each week to see Kentucky heroes like Blacksmith Pedigo and Billy Love, not to mention the World Welterweight Champion himself, Jack Reynolds. Finberg decided the best way to challenge the Savoy was to go big — literally. He announced his first show would take place in January of 1933 at The Armory, and it would feature all heavyweights.

The January show went off, despite some drama backstage before the event, but it was hardly a roaring success. Finberg drew 1,283 fans to a building that, reportedly, would house over 7,000 when the Allen Athletic Club ran its Police Benefit Shows in the 1950s. His second show drew 1,275 in February. Finberg offered free admission to ladies that night, but to gain entry, the ladies still had to pay the state required amusement tax — just one of the many reasons Blake refused to play ball with the State Board.

Finberg’s third show on March 14 drew 2000 fans, but only 750 of those admissions were paid. Finberg offered free admission to women, paper boys, and members of the Louisville baseball team.

The big show in the 1930s was the coveted Derby Eve event that took place at The Armory. The tradition began when a wrestling show took place at The Armory back in 1914, but it had since become a hotly-contested event. Each year, the boxing and wrestling promotions were required to submit a potential Derby Eve card, and the state would reward the date to the promotion with the best card. Politics and shenanigans were often involved in the awarding of the Derby Eve slot, but that’s another story in and of itself!

Still eager to make a splash on the Louisville sports scene, Abe Finberg bypassed the whole submission process and booked The Armory directly on May 5, angering not only Blake but the manager of the Dell Boxing Club. He began advertising and promoting an all heavyweight card for May 5 featuring — you guessed it — Karol Zbyszko and Gus Sonnenberg.

Of course, as we’ve already established, the wrestling show never took place. On April 25, after some persuasion from the State Board of Athletic Control, Finberg gave up the Friday night Derby Eve spot and gave it to the Dell Boxing Club. With so little time to prepare and promote, the boxing show was a financial disaster. The State Board only made matters worse, going around Dell’s back and promising the boxers they’d be paid in full what they were promised despite the bad box office.

Abe Finberg was out of the wrestling game, and so was the Olympic. Within a matter of weeks, the State Board of Athletic Control was out as well. A judge ruled the 1928 amendment to the law governing fight sports to be unconstitutional, and the State Board was stripped of all control over wrestling state-wide.

Within a few years the landscape of wrestling would undergo several changes. A new authority would be created to govern boxing and wrestling. Like its predecessor, the new athletic commission would be staffed by political cronies, but this time there, there would be no ambiguity in the writing of the law. Blake tried to fight the law anyway, but this time, the law won.

In 1935 and even bigger seismic shift would shake the Louisville wrestling scene. A disagreement over finances after the Savoy Club’s Derby Eve wrestling show would lead to a parting of ways between C.B. Blake and his booker Heywood Allen. Blake would find a new booker while Allen would partner with Francis and Betty McDonogh to open a new promotion: the Allen Athletic Club.

But that, too, is a completely different story.

I can’t say for certain if that ticket — which is still available on eBay as of this writing, by the way! — is real or not. I haven’t seen it with my eyes, and it would be miraculous for a piece of paper to survive in the condition shown on the listing. The show never took place, but the show was booked, and tickets were sold.

Maybe it’s real. Maybe it’s a facsimile. It certainly has a story to tell.