Scholarly approach to lucha libre films a touch dry

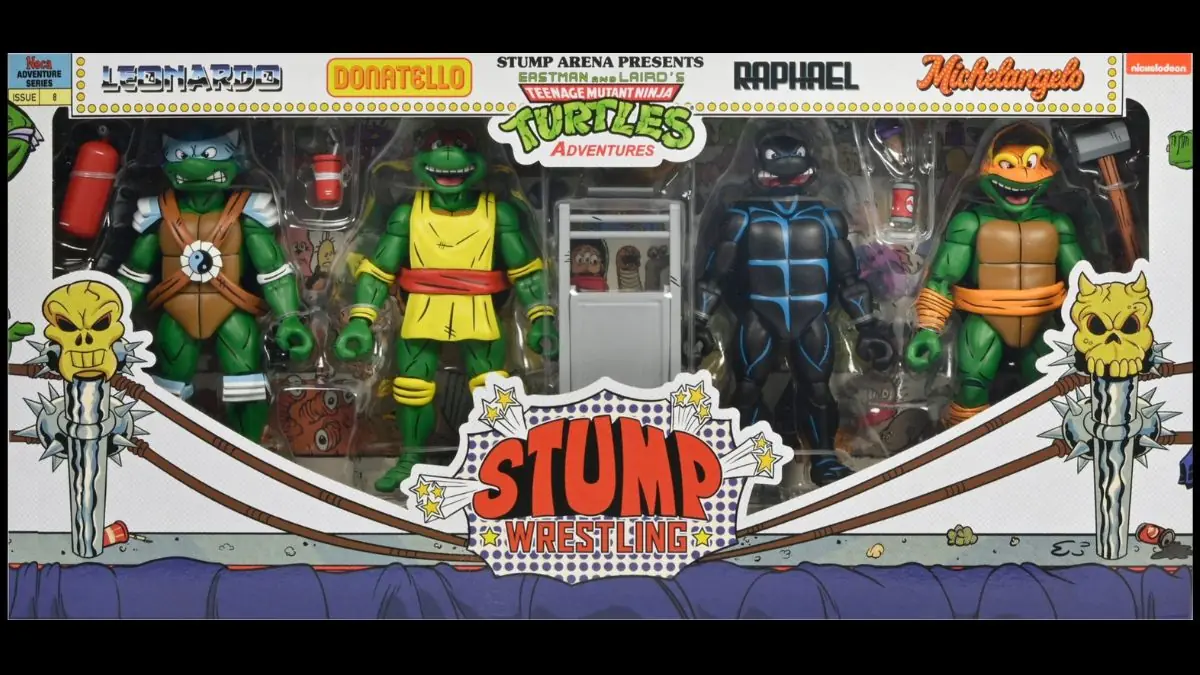

At its best, lucha libre is incredibly colorful, vibrant, with the audience pulsating and the wrestlers zip-zapping in and around the ring. It’s deeply entrenched in the culture of Mexico in a way that pro wrestling has never been in the United States or Canada.

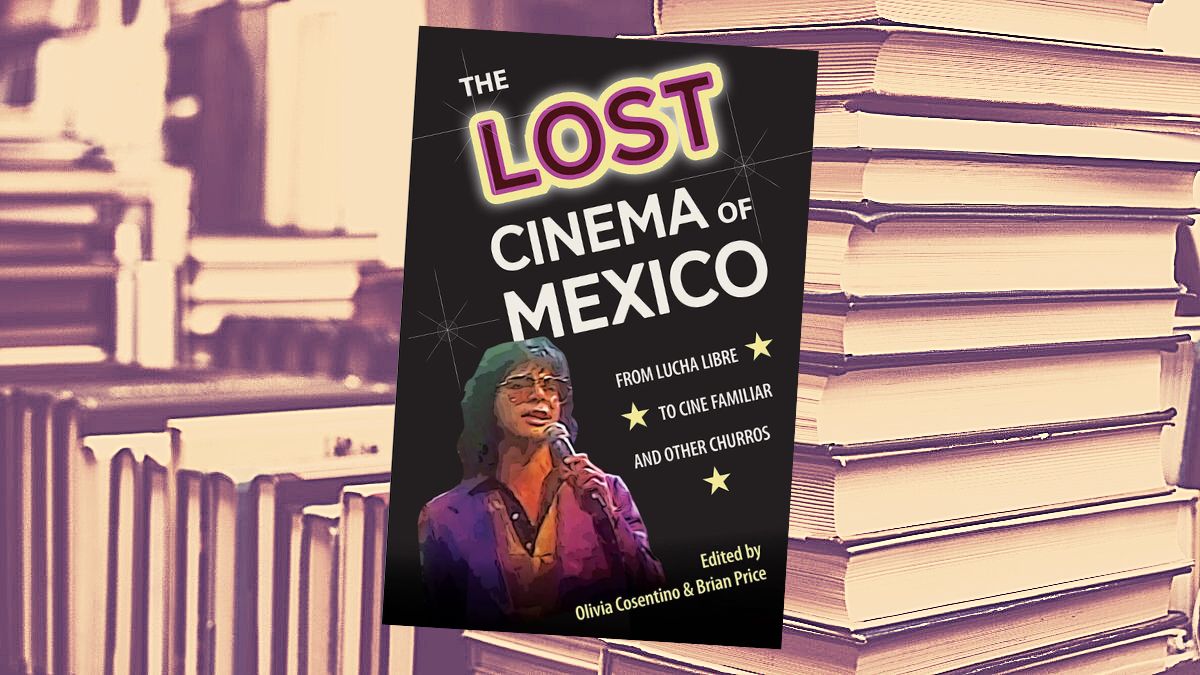

Then along comes a book with an intriguing title — The Lost Cinema of Mexico: From Lucha Libre to Cine Familiar and Other Churros — and it arrives with great promise.

Alas, it’s the opposite of what I think of lucha libre. It’s lacking in color and deeply academic.

Now, that’s not to say that it’s not without its merits; instead, I’m laying it out for you — the scholarly approach will educate you and likely challenge you to go hunt down some of these hard-to-find lucha libre films of the 1960s, and, perhaps re-watch them with a new eye.

The book is edited by Olivia Cosentino and Brian Price, and came out from University of Florida Press in February 2022. With a hefty hardcover price tag ($95 at the university’s website), it’s obviously aimed at academia, though fortunately there’s a paperback version as well at a much more reasonable cost, listed at $35.

Here’s the promotional words for it, which sets it all up better than I can, since this is about more than just lucha libre:

The Lost Cinema of Mexico is the first volume to challenge the dismissal of Mexican filmmaking during the 1960s through 1980s, an era long considered a low-budget departure from the artistic quality and international acclaim of the nation’s earlier Golden Age. This pivotal collection examines the critical implications of discovering, uncovering, and recovering forgotten or ignored films.

This largely unexamined era of film reveals shifts in Mexican culture, economics, and societal norms as state-sponsored revolutionary nationalism faltered. During this time, movies were widely embraced by the public as a way to make sense of the rapidly changing realities and values connected to Mexico’s modernization. These essays shine a light on many genres that thrived in these decades: rock churros, campy luchador movies, countercultural superocheros, Black melodramas, family films, and Chili Westerns.

Redefining a time usually seen as a cinematic “crisis,” this volume offers a new model of the film auteur shaped by productive tension between highbrow aesthetics, industry shortages, and national audiences. It also traces connections from these Mexican films to Latinx, Latin American, and Hollywood cinema at large.

The essay I focused on was “On Virgins, Malinches, and Chicas Modernas: The Star Power of Lorena Velázquez in Lucha Libre Cinema,” which was written by David S. Dalton, who is an associate professor of Spanish at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. He’s assuming right from the get-go that you know about lucha films in Mexican culture, and I’m nothing more than a novice, so was in over my head from the start.

For those unfamiliar, El Santo became a huge star in Mexico on the big screen as well as in the ring. He made dozens of films, facing zombies, vampires, and other monsters, and always saving the day. The popularity of his movies resulted in others, like Mil Mascaras, getting their own movies.

Instead of going down the usual route, and celebrating the luchadors that starred in these movies, Dalton turns the focus to Lorena Velázquez, one of the top female stars of Mexican cinema from the late 1950s into the 1970s. Sex appeal — vamping — was a big part of her career. Her role as Thorina, queen of the vampires in El Santo contra las mujeres vampiros, made her a big star.

Dalton explores how her career grew through her appearances in the lucha flicks and, as her star power rose, how the roles changed, become less just about the sexiness and more about the character.

Velázquez is then given her own starring roles as a luchadora. This section was fascinating, as I was unaware of the state of women’s wrestling in Mexico City. Women started wrestling in Mexico in 1935, but were banned in the capital itself, Mexico City, from 1956-86. These films with luchadoras were an attempt to change public thinking (well, politicians) while also entertaining.

What Velázquez wasn’t, though, was a trained wrestler, and, apparently were few of the other star luchadoras. Attractive women were on the bill rather than the active wrestlers, many of who filled in as stunt doubles in the wrestling sequences.

Dalton argues, though, that even if the luchadoras were front and center, they weren’t able to win the day. “A principal theme is the wrestling women’s relative helplessness in a patriarchal society,” he writes.

Ultimately, Dalton’s point is that Velázquez and her appearances in lucha libre films was one aspect of the growth of women and their roles in Mexican culture, chicas modernas.

It’s an interesting take, and I learned a lot through his essay … but that doesn’t mean that I didn’t want to see colorful photos of Velázquez, El Santo and the rest.

The rest of The Lost Cinema of Mexico is well outside my wheelhouse, so I really can’t offer much of a take on the other non-lucha pieces.