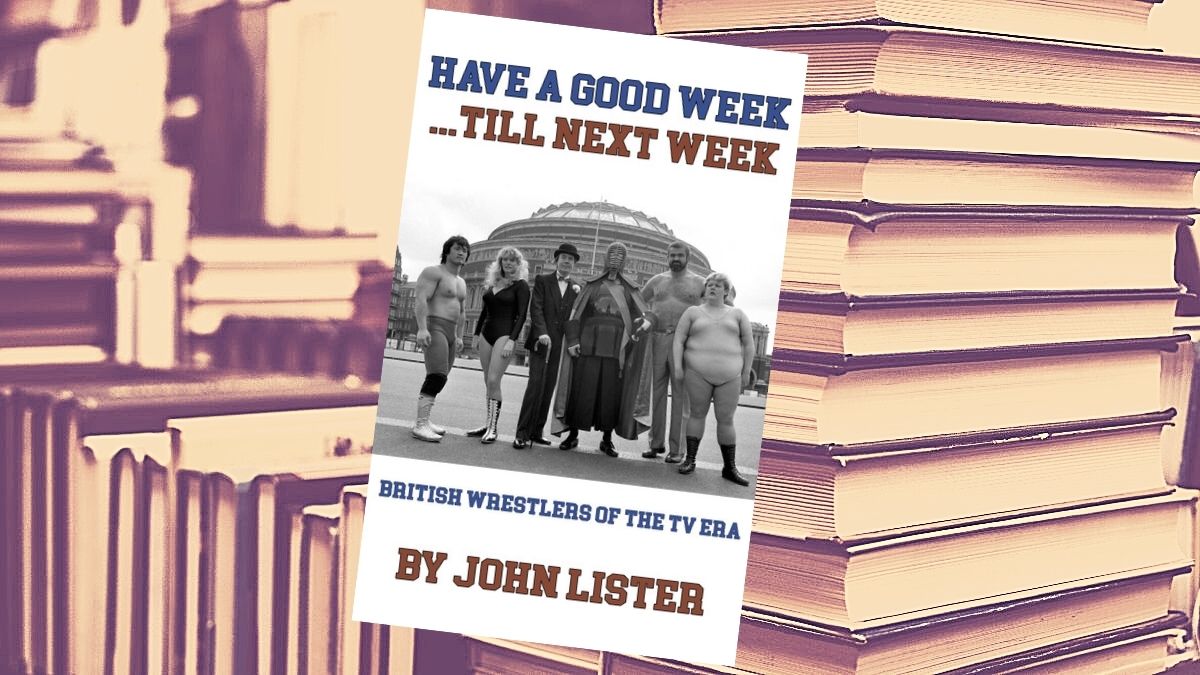

Lister’s collection of columns on UK stars holds up

With most publications centred on British pro wrestling’s golden age either long out of print, or written during a time where kayfabe was ubiquitous, it is refreshing to discover a contemporary release which captures many of the characters and stories from the era and refuses to dumb down its content for the reader. The publication of Have A Good Week… Till Next Week: British Wrestlers of the TV Era from respected journalist and historian John Lister is a title which focuses on many of the contributors from a national industry that deserve to be remembered. Decades after the glory years of television wrestling came to an end, Lister breathes new life into the legends and legacies of those who created the weekly mayhem and mat magic in the grunt ’n’ groan game. The heroic blue eyes (babyfaces) and villains of the ring, who entertained millions of households each week are profiled in this 400-page account.

For those unfamiliar with Lister’s monthly articles on British wrestling history, this book is the culmination of six years’ worth of material prepared under his Greetings Grapple Fans regular articles (titled in tribute to British wrestling commentator Kent Walton’s trademark welcome from ringside). The series, renowned for its informative yet accessible prose, was a fixture within the pages of the now-defunct monthly publication, FSM (originally Fighting Spirit Magazine). Signifying the end of that editorial run, Have A Good Week… Till Next Week is named after the infamous signoff catchphrase that Walton used at the end of each of his weekly broadcasts.

This reviewer first became aware of John Lister through his work on Power Slam in the mid-1990s. He had started writing for the magazine after the recommendation of contributing writer Rob Butcher (on a personal note, Butcher was also a key tape trader who supplied content to this writer before his business was acquired by Global Wrestling Imports in the late ’90s). After some on-and-off stints due to his other work commitments, Lister would eventually join the writing team of FSM in 2010. Indeed, FSM deserves some credit for investing in the original series which led to this compendium. It is likely that the level of research required for a book of this magnitude would have not been financially viable without the backing of a newsstand magazine, and this afforded the author of this title the time and resource necessary to chronicle an industry on multiple levels. The result is an honest overview of the sport during its rise and fall, while maintaining a level of journalistic integrity that enables readers to understand why it grew and declined in popularity. Nevertheless, Have A Good Week… Till Next Week fuses facts with a fondness for yesteryear.

On the cover and chapter headings, Lister has elected to use the very typeset which was featured in the twilight years of the professional wrestling coverage on the commercial network ITV (Independent Television). He even went so far as to colour match the font from the opening titles. It is this level of detail which conjures up a level of nostalgia that will bring warmth to many readers who witnessed wrestling as a weekly fixture on small screens throughout the United Kingdom.

Though the timeslot 6:05 p.m. has earned a soft spot in the wistful minds of veteran wrestling enthusiasts across the United States, the British grapple fans who tuned in during the heyday of nationally televised wrestling will remember that everything stopped at 4 o’clock. Each Saturday afternoon around that time, World of Sport showcased its coverage of professional wrestling just before the announcements of that day’s football (soccer) results.

In recent years, the term World of Sport has become synonymous with the style of British wrestling that was broadcast during this era, but this is not entirely true. World of Sport was the umbrella name for an afternoon’s block of mixed sports airing on ITV every Saturday from 1965. But this was by no means the start of television wrestling in Great Britain. There had been coverage of wrestling on the channel since November 1955, and for a few years after World of Sport ended in 1985. In terms of viewership, the Mick McManus and Jackie Pallo feud is generally accepted as the peak of small screen grappling. Their May 25, 1963 rematch on the same day as the FA Cup Final (the culminating match of the most prestigious soccer tournament in England) was likely the pinnacle, which some claimants insist drew an armchair audience of 16 million viewers. In any event, their series brought in the highest UK ratings that professional wrestling would ever attract on the telly. Nevertheless, the name World of Sport will likely be forever associated with the halcyon days of professional wrestling in the United Kingdom.

The actual wrestling provided during this era was provided by Joint Promotions, a cartel of wrestling promoters who operated across the United Kingdom in an organised system similar to the National Wrestling Alliance, which had an industry monopoly across North America at the same time. This eventually changed in the 1980s when All-Star Wrestling, a Merseyside enterprise led by Brian Dixon, secured a portion of the ITV coverage, which would eventually be moved to a lunchtime slot when World of Sport ended. Later, the WWF would sporadically be featured as the network elected to rotate its wrestling footage in a shared agreement between Joint, All-Star and the Federation in subsequent years. This revolving system was brief; ITV’s head of programming Greg Dyke made the decision to axe all wrestling from the network in 1988.

As for the matches, the now-famous ‘World of Sport style’ was contested under Admiral Lord Mountevans rules, a distinct framework in which bouts were fought in rounds, and most frequently “two falls, two submissions, or a knockout would decide the winner.” A unified set of rules had been instituted in post-WW2 Britain to remove the outlandish image that had been created by the growth of ‘All-In’ Wrestling in the interwar years and would largely remain in place until the popularity explosion of ‘American Wrestling’ within British shores in the 1990s.

Despite the massive cultural influence of British televised professional wrestling, which resulted in household names such as McManus, Pallo, Big Daddy, Giant Haystacks, Pat Roach and Kendo Nagasaki, it has been largely dismissed by modern media covering pro wrestling history in the United Kingdom. Many magazines printed in the United Kingdom seem to promote the idea that wrestling really only started in 1984, with the national expansion of the WWF. It is somewhat sad that the heyday of UK pro wrestling remains somewhat ignored, despite the popularity of modern BritWres in the new millennium.

Have A Good Week… Till Next Week goes a long way in rectifying this by providing a tremendously comprehensive overview of a national institution that was so important to the global landscape of wrestling history. Its subtitle, British Wrestlers of the TV Era, promises readers a series of biographies on some of the best and brightest stars who made their way into living rooms across the nation, but this book offers so much more than that.

The book is much like a reference guide, and offers a flexible format which will appeal to both ardent historians and casual fans. Each chapter is a standalone biographical summary of a wrestler or a matter relevant to the subject of British wrestling. Beyond the expected nostalgia that will be offered to the home readership by Have A Good Week…Till Next Week, there is much to interest fans from other geographical areas. In addition to profiles on domestic superstars such as Les Kellett and Jim Breaks, or memorable female talent such as Mitzi Mueller and Klondyke Kate, there are many names who will be familiar to readers across the pond. Indeed, there are articles on Chris Adams, the British Bulldogs, Billy Robinson, William Regal (who veteran fans might remember as Roy Regal, before he crossed the Atlantic to find fame in WCW and WWE), Adrian Street and Dave Taylor. Although the book might have benefitted from some illustration to supplement the internal text, the strength of the writing provides a lurid depiction of the circuit and its memorable talent. The stories within the 400 pages help preserve key events, such as the mass exodus of unhappy talent from Joint to All-Star, an examination of the overall decline of an industry before the cancellation of ITV’s weekly coverage of the sport, and the backstage politics that encouraged some of the promising stars to flee the country in the hopes of finding greater opportunity.

Beyond the advertised profiles of almost 60 key talents, there are eight historical essays towards the end of the book. These highly digestible chapters cover a diverse array of topics such as the aforementioned FA Cup Final cards (which was the biggest pro wrestling show of the year for ITV viewers), the Holiday camp circuits (which were essential places of employ for many), and an overview of Joint Promotions among other chapters. The essays are well crafted and are punctuated by interviews with many of the key personalities who helped define the TV era.

Veteran writer Lister has left few stones unturned and presents us with the facts, after separating it from the fiction, and provides the historical analysis one would expect from a journalist of his esteemed calibre. These all amount to provide a multitude of insights on various facets of a major domestic institution that was uniquely British, yet part of a global industry.

After all, the British influence helped usher in the modern junior heavyweight style of wrestling. It was a circuit which introduced us to the innovative likes of The Dynamite Kid and Rollerball Rocco and was an important area which refined the skills of international talent such as Satoru Sayama (who found fame as the first incarnation of puroresu’s Tiger Mask), ‘Cowboy’ Bret Hart, Fuji Yamada (the future Jushin Liger), and the up-and-coming high-flyer ‘Bronco’ Owen Hart before they realised their destiny as true ring greats. The technical chain matwork perfected by superlative Scots star George Kidd would also influence later generations, having been adopted by Johnny Saint in the 1970s and making its way into the 21st century, with practitioners like Zack Sabre Jr., Pete Dunne and Jack Gallagher employing their version of the style. Moreover, ITV wrestling alumni such as Regal, Taylor, Dave ‘Fit’ Finlay and Robby Brookside have been among the most influential trainers of current talent within wrestling’s biggest international stage.

So, if the ITV professional wrestling generation helped forge the industry that now is, Lister has helped preserve the way it once was for a new fanbase to enjoy. Lister’s website, prowrestlingbooks.com, is an achievement in the review of grappling literature, past and present. His other domain, itvwrestling.co.uk, provides an amazing archive of material which he has developed for years on the very subject that this book is based.

A paperback sibling to the latter online resource, Have A Good Week… Till Next Week is the culmination of years of dogged research by Lister and, in this reviewer’s opinion, serves as his masterpiece. Although some of Lister’s other writings might offer more analysis on their subject, none have the vast scope of this entry. It is the sheer ambition which separates this from his other accomplished, and highly readable, grappling titles covering a range of topics including an overview on the history of Extreme Championship Wrestling and a travelogue into the world of puroresu.

Available worldwide on Amazon and other retail outlets, Have A Good Week… Till Next Week is an essential addition to the bookshelf of anyone interested in the rich, and varied, history of British professional wrestling during its most famous era.