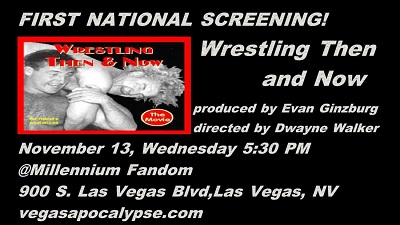

Wrestling Then & Now, a nearly 20-year-old documentary shot on video with a negligible budget but plenty of passion, is being screened this week at The Millennium Fandom Bar in Las Vegas on Wednesday, November 13th. Slam Wrestling caught up with both director Dwayne Walker and producer Evan Ginzburg to learn about the production of the film, and what makes it deserving of finding a new audience today.

Evan Ginzburg, Producer

Walker, an independent/underground filmmaker from California, and Ginzburg, author of the Wrestling Then & Now newsletter and associate producer of The Wrestler, were on different career and social planes until they were introduced through mutual friend Jeff Archer, author of Theatre in a Squared Circle.

Dwayne Walker, Director

Walker, who was admittedly not a wrestling fan, was starting to get intrigued by what draws certain people into the often manic world of pro wrestling. He found interest in seeing Ginzburg, a soft-spoken, mild-mannered teacher who also had a group of friends that went by names like Homicide, Low Life, and Killer.

The “Killer”, naturally, was Kowalski. In another coincidence that ended up drawing Walker and Ginzburg closer together, Walker had worked with Kowalski on a promotional tape called Walter “Killer” Kowalski’s Miracle Video. In it, Kowalski was seeking to impart his life’s philosophy of avoiding negativity — and picturing yourself in a flaming, golden sunset.

Walker was entrusted with creating this effect for Kowalski, but with limited effects capabilities at his disposal at the time, he struggled to perfect the look without making Kowalski himself come out looking red, or even green. Turns out that it didn’t matter — Kowalski was happy with the outcome, and Walker and Ginzburg now shared a couple of friends.

Ginzburg then convinced the filmmaker to cross the country and spend three weeks in New York City going to independent wrestling shows, capturing match footage, and interviewing wrestlers. Walker remembers bringing his Canon XL1 for the project, and Ginzburg reports that they captured over 90 hours of footage for what ended up being just over an hour as a finished product. “The things was shot on pennies,” laughs Ginzburg. “It’s an absolute low-low budget film from the heart”.

As mentioned in the SLAM! Wrestling Movie Database review of the film, the interview segments are loose in terms of structure. Walker explains that often he or Ginzburg would ask just one question and then just let the interviewee go on their own storytelling path. “You kind of got the feeling that, looking back now, a lot of the wrestlers didn’t have chance to talk about what they were really motivated by,” reasons Walker, accounting for how willing the wrestlers were to unload some pretty personal feelings.

One of the more revelatory moments in the film is when the wrestler Blood is explaining how he learned to intellectually deal with pain, and how he first used that ability not for the ring but for an abusive relationship with his mother. Walker says that he was very affected by that segment and finds it just as impactful watching it now. The whole movie, for Walker, strikes him as relevant today, “with the wrestlers as creators of personas, characters, trying to be true to their characters, and going through enormous sacrifices.”

For Ginzburg, the connection to many people in the movie was strong, and is one of the reasons he’s so pleased to see the movie out for public viewing. “A half dozen people in that movie are gone, they’re gone,” he laments. “Nikolai, Bobby Lombardi, Tiger Khan, Walter, Don Arnold. Seventeen years after the fact, we feel the film has some historic value because these people are no longer with us. These were my friends”.

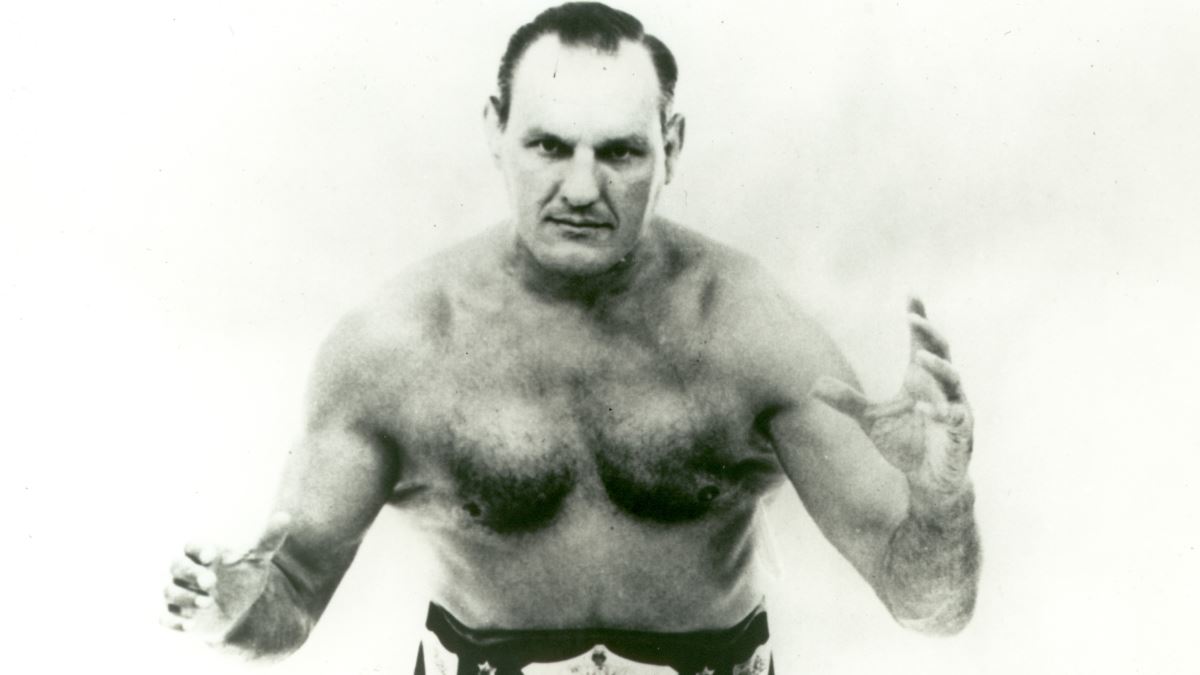

Killer Kowalski

Ginzburg sees this film now, therefore, as part-tribute to lost friends, but he always knew that it was a love letter to the independent wrestling scene of the late 1990s and early 2000s. Even in those days, when the on-line wrestling community was in full swing, he felt that most fans couldn’t comprehend the life of an independent wrestler.

“What people do not understand, except the closest follower of pro wrestling,” he explains, “Is that indie guys are making nothing, or gas money, or the traditional two hot dogs or a handshake. So, then these guys are giving their bodies a physical pounding and risking physical injury. There are wrestlers who end up in wheelchairs, in pain with pill addictions, stemming from what they did in the ring.”

This is more commonly known now, and in the early 2000s it was starting to come out into the public consciousness. Still, Ginzburg recalls that they walked a fine line between illuminating the risky life a wrestler chooses and cautioning them to be more careful. “You’re dealing with friends so you’re kind of walking on edge, but at the same time you’re a filmmaker,” he admits. Specifically, he wonders in hindsight if he could have advised “Low Life” Louie Ramos about how far he pushed himself to entertain the crowds, telling the tale of how Ramos suffered a collapsed lung while wrestling and still pushed himself to carry on.

Summing up the final outcome of a wrestler’s career, Ginzburg recounts a simple truth that both legendary and indie wrestlers have imparted to him: “I’m always in pain.”

Walker looks back upon the earliest production of the film, when he would burn 100 DVDs to send out, only to have someone in the original cut demand that something they said be removed – which meant, of course, 100 more DVDs to burn.

After the success of The Wrestler, the film was re-produced with Ginzburg’s accomplishment in the credits to help in its promotion. The film was featured at an art gallery show in California, found its way onto Amazon Prime, and is now receiving its very first public screening at The Millennium Fandom Bar.

Walker, whose past credits included a look at the existence of Christian fundamentalism in Bible Madness, and an exposé of abuse in a Louisiana Christian reform school titled They Didn’t Forget, has created the event in Las Vegas as a means to foster networking opportunities in his new home, having only lived in Vegas for under four years.

He believes in the power of film and video to tell stories that aren’t widely known — and in the case of They Didn’t Forget, it garnered enough attention to assist in investigations of the abuse allegations, even leading to a follow-up film called They Fought Back.

These are heavy subjects, and, on the surface, a look at pro wrestling may seem like a trite subject by comparison. Walker doesn’t see it that way, though, and feels that there is much to be learned about a still much-misunderstood form of entertainment. “I see more of a kinship with the people now than when I filmed it,” he admits.

The screening of Wrestling Then & Now at The Millennium Fandom Bar is free of charge. The venue is located at 900 South Las Vegas Boulevard, #140.

RELATED LINKS:

Film Review: ‘Wrestling Then & Now’: Seeking truth in a business built upon deception