Roxanne Barnes remembers the shriek. She was nine years old, standing in her grandmother’s bedroom in Indiana after returning from a family picnic. In the next room, her mother took a phone call and screamed as her aunt and grandmother raced to find the source of the commotion. She remembers the words her mom spoke: “Ray’s dead.”

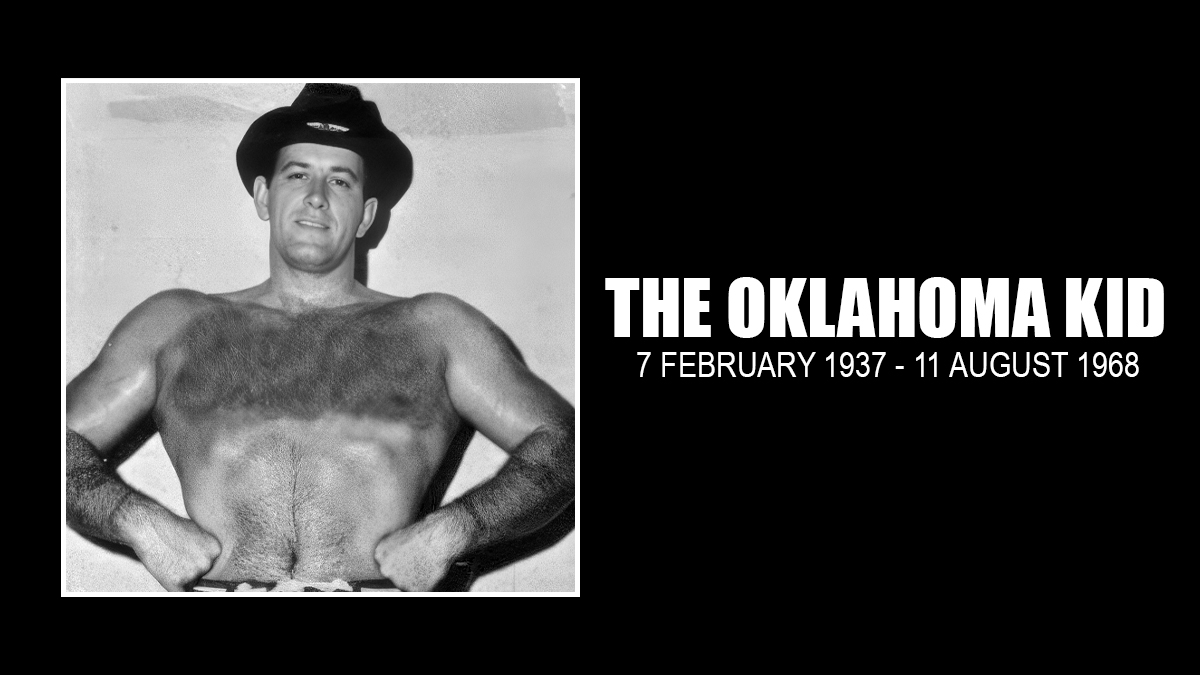

Fifty years later, Barnes confesses to childlike curiosity as she hunts high and low to piece together the life of her father Ray, a.k.a. Elmer Ray Gearlds, wrestling’s Oklahoma Kid. “When it comes to him,” she says, “it’s like my mind reverts back to being a nine-year-old because that’s all I knew.”

The Oklahoma Kid is one of wrestling’s great mysteries. He was a Stetson-hatted cowpoke, big as a house, who turned up out of nowhere, shot to the top of the business, made a national magazine cover, and then was dead at 31, all in just a couple of years. For decades, rumors have circulated about his death in an Australian hotel room on August 11, 1968, with speculation ranging from a heart attack to wrestling’s first steroid fatality.

Barnes, one of the Kid’s two children, has dug into the events that triggered that phone call to her mom. With the input of medical professionals, she is satisfied that an undetected kidney disease contributed to her dad’s death. More than that, though, she wants to know about his life. Because of divorces and wrestling trips away from home, her time with him was limited. A lot of the Kid’s relatives have died in the last 50 years, so Barnes has been putting the story together, sliver by sliver, with the help of court clerks, wrestling researchers, a few family members, an Australian video, and Dominic DeNucci, the last man to see her father alive.

“I have been searching for things on him for years. Some of it is like a soap opera,” she says. “I was absolutely a daddy’s girl.”

THE KENTUCKY KID

The Oklahoma Kid was not from Oklahoma; it’s doubtful that he ever set foot in the state. Gearlds was born February 7, 1937, in Beech Grove, Indiana, the oldest of nine children. He was only about three when his family moved to Cumberland County, Kentucky, where his father worked as a logger. A strapping lad who would grow to be 6-foot-6 and 280 pounds, Gearlds played basketball in high school, then fibbed about his age to get into the U.S. Air Force. He was stationed at Sampson Air Force Base in New York with the 3657th Training Squadron in 1955, among other assignments.

A marriage at 17 ended in divorce, and when Gearlds moved to Indianapolis following his military service, he met and married Kay Shotts. There was still no hint of a wrestling career. In 1959, Gearlds worked for a time with his brother Ervin churning out baseball bats at a factory in Louisville, then returned to Indianapolis to a meat packing plant. “He stood up and straddled cows as they came down the chute and hit them in the head with a hammer and knocked them out,” his daughter says. “I guess when they said later that he wrestled cattle, it wasn’t a stretch.”

Neither the butcher work nor the second marriage lasted, and Gearlds was working as a bouncer at an Indianapolis bar when someone lost to history suggested he take a stab at pro wrestling. At that point, his career path zigged and zagged. Gearlds first wrestled as Ray Gordon, an offshoot of his given name. But confusion loomed: another Ray Gordon, a 235-pound veteran from New Zealand, was working in Missouri at the same time Gearlds was starting his career one state to the east.

That led to name change No. 1. Gearlds became Bob Atlas and Mighty Atlas. While the record book is confusing, one of his earliest matches was Greek mythology in trunks — Atlas met the Mighty Hercules on Christmas Day 1965 in Indianapolis. In April and May 1967, Gearlds used the Atlas identity in St. Louis and Indianapolis, where he worked for Dick the Bruiser and Wilbur Snyder’s promotion.

His daughter saw him wrestle at the Tyndall Armory in Indianapolis and understood while the beatings weren’t altogether real, it didn’t matter. “I’m a nine-year-old little girl who thinks my daddy can whip the world. I figured he could just whip everybody. I didn’t have to worry about him,” Barnes says. While Gearlds had remarried a third time by then, a visit to his two children by Kay became an event.

“When Daddy would come home, all the kids on the street would come running,” she recalls. “He would take me and my brother backstage and we got to meet Mitsu Arakawa and Dick the Bruiser and Wilbur Snyder. Big Bad John was at our house several times.”

In addition to his Atlas guise, Gearlds worked as Ray Gordon as late as February 1967, when he dropped a three-fall match to Herb Larson in Hayti, Missouri. His ring garb stood out as much as his wrestling. The Courier-News of Blytheville, Arkansas, said he “looks like Western television hero Clint Walker.” It was a get-up for the times when Gunsmoke and Bonanza were top hits on TV and cowboys like Bill Watts and Bob Ellis were among wrestling’s top draws.

COSTUME CHANGE

Within a few weeks, Gordon and Atlas were relegated to the land of retired gimmicks and the Oklahoma Kid was born. It’s likely that the Oklahoma reference was a play on promoter Jim Barnett’s Sooner State origins. Barnett co-owned the Indianapolis promotion before Bruiser and Snyder, as well as the Detroit promotion before The Sheik, who would become the Kid’s promoter and mortal in-ring enemy.

By June 1967, there was no confusion about his identity. Gearlds was working in the Great Lakes area for The Sheik and quickly became a fan favorite. He debuted in Cobo Hall in Detroit on June 2 against Big Bad John and fought him again in Marion, Ohio, five days later. Next up was a date in Dayton, Ohio, against The Great Amara, the future Abdullah the Butcher. In Cincinnati, the Kid had a trio of main events against The Sheik, with the evil one from Syria taking the rubber match as Gearlds couldn’t continue in the third fall because of blood. In Marion on November 1, he split the first two falls with The Sheik, then the Kid got the boot in the third when he hit and stomped referee Ron Tracy. He delighted fans with his bulldog headlock finisher in which he grabbed his opponent like a calf and rode his head into the canvas.

“He made a real splash. He was a good worker,” says Dave Drason Burzynski, a member of the official Oklahoma Kid fan club and a future wrestling manager. “He was very down to earth when he talked to me, a 12-year-old kid getting his autograph.”

The Kid’s other opponents were main eventers: Jess “Bull” Ortega, Bull Curry, Baron von Raschke, and John (Kentucky Butcher) Quinn. He also tagged with Chief White Owl in feuds with the Fabulous Kangaroos and Hell’s Angels. White Owl’s widow, Patricia Dahmer, remembers him as a “respectful man. Him and Chief White Owl always had lots of laughs together traveling when they were on the same show.”

By 1968, the Kid seemed to have it made. Since The Sheik put himself on top in his own territory, other wrestlers competed for runner-up honors. The Kid was in the mix as U.S. Rookie of the Year, as named by the Wrestling Fans International Association. The Wrestler magazine asked if he could unseat Ellis as top bronc in the business. Wrestling World magazine set him up for a cover story and Wresting Revue did a long if bogus feature on him with a plot twist lifted from “The Beverly Hillbillies.”

“I got an offer to play ball at Oklahoma University and I did right well as a freshman,” as writer Jay Doss imaginatively quoted the Kid. “But then my daddy needed help on the ranch. He had about 350 head of cattle. So I quit school and went to ranching for a while to help him out. Then, after they struck oil, nobody in the family had to work anymore so I told them I thought I’d try my hand in wrestling.”

In July, the Kid got the call to go to Australia, which Barnett had turned into one of the hottest properties in the world. His last match before he went overseas was on July 26 in Dayton, a draw with Ortega. “He had come to visit us the week before he was leaving to go to Australia,” his daughter recalls.

She never saw him again.

THE UNTIMELY DEATH

Gearlds arrived in Sydney, Australia, on August 7, 1968. DeNucci, a top star in the country, picked him up at the airport, took one look at him, and couldn’t believe his size — he was bigger and wider than even Tex McKenzie, another cowboy Barnett used with great success.

But there was not much time for fraternization — wrestling and travel took precedence. On August 9, the Kid was the third-to-the-last wrestler eliminated in a battle royal in Sydney Stadium. The next morning, he won his first singles match in the country, a TV studio tussle with Johnny Boyd.

From there, the crew flew to Melbourne for a show that night at Festival Hall. The Kid scored a huge victory over Killer Kowalski in just 90 seconds, a sure sign that Barnett intended to propel him to top billing. Returning from his triumph, the Kid went out with DeNucci to get a bite to eat. It was about 11 p.m. But DeNucci knew of a 24-hour Italian restaurant called Pelligrini’s near the Southern Cross hotel, where they were staying.

“We go in and we got something to eat, and we got one glass of wine, small glass too. We go back to the hotel, and he said, ‘I’m going to retire.’ I said, ‘Go ahead, go sleep. I’m going to go upstairs too,’ ” DeNucci says. The wrestlers made plans to meet in the lobby at 9:30 a.m. the next day to go to another TV taping.

DeNucci was in the lobby at the appointed hour.

The Kid was not.

DeNucci stayed for a while, then assumed the Kid had taken a taxi or found his own way to the TV studio. He did not call the Kid’s hotel room, but instead went to see Barnett at the station, anticipating the wrestler would be there. Now pulses quickened. Barnett picked up a telephone and called the Southern Cross. “Just me and him now, Jim Barnett and myself, because at that time, the telephone is against the wall. He called the manager and we were talking. The guy said, because I could hear, I was close to him, he said, ‘He’s there, but he’s not there.’ Inside to me, I said, ‘Oh God, he’s dead.’ ”

According to news reports, hotel staffers forced themselves into the room sometime after noon and found the Kid slumped on his bed. It looked as though he had been trying to pull on a boot and get dressed. He had been dead for an estimated five or six hours.

At the TV station, the show had to go on. “Dominic, I don’t want you to open your mouth with the boys. We’ve got 47 minutes of television to do. Don’t say nothing. We’ll tell the boys after,” Barnett said, adding it was OK if DeNucci didn’t want to wrestle under the circumstances.

“I said, ‘No, I don’t want to wrestle today.’ But anyway, after the television finished, we called all the guys, that was my job, to call all the guys in one room, and Jim Barnett said, ‘He’s dead.’ Nobody said one word, nothing, nothing. What are you going to say? The guy, he just came in, he come on Tuesday, he died on Saturday [actually Sunday]. I said, ‘Holy shit.’ ”

To the press and police, Barnett said he saw the Kid after the Kowalski match and reported he appeared to be fine. “I didn’t see Gerald [sic] take any heavy falls. It wasn’t a rough match.”

Back in Indiana, the phone rang in the house of Barnes’ grandmother; it was the president of the Kid’s fan club on the line with the bad news. U.S. and Australian authorities detained DeNucci in Melbourne for two days of questioning since he was the last to see Gearlds alive. The Kid’s body was embalmed and the U.S. Consul office took custody of it. A form that foreign governments fill out when they transfer a dead American to the United States cited myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart muscle, as the cause of death. The office sent the reports to The Sheik and Gearlds’ third wife Ruth in Celina, Tennessee, where the Kid was buried in late August.

Lou Sahadi’s cover story on the Oklahoma Kid ran in Wrestling World that month. The Kid never got to read it.

WHAT HAPPENED?

It was, the Detroit Body Press program said, the “Tragedy of the Year,” noting that Barnett had lined up a four-week engagement for the Kid to increase his profile. “The international exposure could be valuable later, if I become champion,” the wrestler said. The account echoed the conventional wisdom that Gearlds died of a heart attack.

A more sinister explanation was advanced by Cowboy Frankie Lane, who was the resident wrestling cowboy in Australia starting in September 1969. “He was six-feet-six, 290 pounds and he wanted to get bigger, so he got on steroids,” Lane told a Canadian reporter in 1999. “He was getting out of bed one morning and fell back dead of a heart attack.”

For years, Barnes had no answers about what happened to her dad. Death and divorce can be painful and many family members did not know or want to follow up on Gearlds’ mortality. Barnes’s time was consumed raising her own family. “I didn’t have anything, a few pictures and that was it,” she says.

Half a world away, Geoff Brown was reopening the case. He was an eight-and-a-half-year-old fan in Melbourne when Gearlds died. When the internet unlocked new paths to explore wrestling’s past, Brown remembered the broad-shouldered American who defeated the hated Kowalski in less than two minutes. But all the online world revealed was the Kid’s age and year of death.

Digging through newspaper archives and old wrestling magazines, Brown pieced together a tribute to the Kid for Evan Ginzburg’s Wrestling Then & Now nostalgia publication. “I felt [he] had seemingly been forgotten in wrestling history,” Brown says. The response produced a few leads, but the big break came when Brown took a stroll to the public records office in Melbourne.

“To my great surprise, I was given the file on both the police report and coroner’s report,” he says. The police report was basic and said “no suspicious circumstances” surrounded the Kid’s death. The autopsy was not written for a layman — it said Gearlds died of membranous nephritis and myocardial hypertrophy and failure.

Barnes knew none of that; browsing online wrestling forums was not part of her daily routine. But Brown set up a Facebook tribute page to Gearlds in 2014 as a way of putting his information out there for fans and Gearlds’ relatives to see. One day, Barnes’ children stumbled across it and rushed their mother to the internet. Her oldest son got her in touch with Brown. “It was like a whole new world opened up in front of me,” she says. “It was just amazing to find someone was looking for information about my dad at the same time I was, only they had a lot more than I did.”

Brown in turn directed Barnes to Jim Lancaster (Jim Painter), a veteran of the Ohio-Michigan wresting scene who supplied her with clippings of her dad’s matches from his collection. “From there it just kind of blew up,” she says. “I had ordered wallpaper online and a box came. Probably just my wallpaper and I looked at the box and it was from Jim Painter. ‘What in the world would he be sending me?’ I opened it up and it was a notebook full of magazines, pictures, newspaper clippings, articles, anything I could think of.”

In the last few months, she’s talked to wrestlers like Fred Curry and Quinn who knew her dad, and met DeNucci, who tearfully recounted the Oklahoma Kid’s last night on earth. She got a copy of the coroner’s report from Brown and took it to her physicians for decoding. “My dad’s been gone almost 50 years and I still have no clue what killed him. I’ve heard it was steroids, which I know isn’t true. And I’ve heard it was a heart attack. I just want to know for sure,” she told her doctors. The toxicology report was normal. Gearlds’ kidneys were not. He had advanced kidney disease. The kidneys were prone to clotting and the walls of his heart were hardening, according to the physicians’ review. There was nothing anyone could have done to help the Oklahoma Kid live to fight another day.

Barnes made some Oklahoma Kid T-shirts and sent one to Brown for his detective work. “I think Roxanne discovering the page has been the most satisfying thing about it though, as I know how much it has meant to her and she has become a good friend through it,” he says.

She sat stunned when she watched Libnan Ayoub’s recent Over the Top Rope documentary on Australian wrestling — it contains the only known video footage of the Kid. “I cried for days afterwards. My husband said, ‘You should be happy.’ I am happy he’s in the DVD, but it just brings everything back.” She has traveled from her home outside Indianapolis to some fan events with Lancaster, displaying what she has of the Kid’s memorabilia and looking for old-time fans who might have a memory or two to help her fill in the gaps. She is determined to find every last morsel she can about Elmer Ray Gearlds and she knows where that determination comes from.

“Everybody is telling me you’re just like your dad.”