Professional wrestling is all that Jerry Grey has done since he was 17 years old, in the ring as a wrestler and promoting, and now that he is in the fight of his life against cancer, he finds himself reaching out to fans and colleagues for help.

“I can’t even tell now what the pain’s from, if it’s from the cancer or all the bumps and everything,” Grey told SLAM! Wrestling from his home in Florida.

Unlike some wrestlers (and promoters) who burned through their money, Grey had funds set aside. His many years as a promoter, primarily with sold shows, where the money is upfront and the promoter just has to make sure the card takes place, at casinos and other locations, had made him a good living.

Grey promoted from 1988 until 2012, when he was diagnosed with colon cancer.

“I was still trying to do shows, and it spread to liver cancer, and it just keeps spreading into my bones, and I wasn’t able to even fly anymore, because I got blood clots after that,” he said. “All my finances that I had from the shows that I’d been doing for years was just drained.”

To help with the financial burden, Grey has a GoFundMe page, and has received help from organizations such as the Cauliflower Alley Club. “He is a really good hearted man that the CAC, me and others have helped, as he helped all of us get over and provided may people with fine wrestling entertainment,” said Cauliflower Alley Club president Brian Blair.

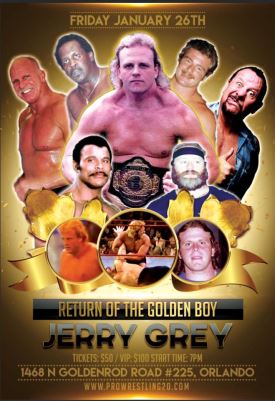

Recently, there was a fundraiser wrestling show at Alex Porteau’s wrestling school. Old friends like Bushwacker Luke, Bugsy McGraw, Rocky Johnson, Brian Blair, Frankie Lancaster, and Bob Cook came out, but the fans didn’t. “Unfortunately, the turnout wasn’t what we expected,” said Grey, suggesting that the venue was a little off the beaten path in a warehouse district near Tampa, Florida.

Podcasts have helped spread the word of Grey’s plight too, including Brian Last’s 6:05 Superpodcast and Jim Cornette had Grey on his show.

The fundraiser show.

During the appearance, “Corny” suggested that Grey was in pretty good spirits for someone who has had so many recent health issues. Grey didn’t deny it, but it also has to do with the subject matter. “Yeah, because I’m talking about old stories. But if I turn the TV on and watch what’s going on now, I get depressed — I mean wrestling. I can’t stand to watch any on TV … I want to see old stuff, I just can’t get into anything nowadays”

Born and raised in Akron, Ohio, Grey was a wrestling fan early. Johnny Valentine was his entry, via television. “My mom was changing the channel and he was juiced, Johnny, with that blond hair, and yelling into the microphone, with his deep voice. I was like, ‘Turn that back! What is this?’ I liked it right then and fell in love with it.”

He remembers plenty more — how Johnny Powers electrified audiences at the Akron Armory, and how attendance dropped off when The Sheik took over. He still has the autographs from stars like Pampero Firpo, and remembers how friendly and engaging Billy Red Lyons was to kids.

A vivid memory was being in the audience on the infamous night when a fan pulled out a gun on the Love Brothers, Reginald and Hartford. “I was just a kid, seeing this stuff, everybody running and the chairs flying, people scared to death. The guy shot the gun and it jammed when he tried to shoot [Hartford]. He shot again, and tried to shoot [Reggie Love]. Then [wrestler] Billy Coleman, I guess he was a pretty brave guy, he ran in front and grabbed the guy with the gun.”

Believe it or not, Grey’s first match came when he was 12 years old, when he got in the ring against Dave McKigney’s bear. “That would never happen nowadays,” chuckled Grey. “I just wanted to get in the ring is all I wanted, because they wouldn’t even let us touch the ring with all the security. I got in the ring and he snapmared me. I remember getting hair in my mouth and everywhere, and he stunk pretty bad.”

As enamoured as he was by pro wrestling, he was equally into working out. “I got real big lifting weight,” said Grey, which made him look older than he actually was.

When his parents moved from Ohio to Florida to start a business when he was 14, Grey was introduced to a different wrestling environment.

In 1979, at the age of 16, Grey looked into becoming a pro wrestler. He called the Florida wrestling office run by Eddie Graham, and talked to Graham’s right-hand man, Hiro Matsuda, who told him to study amateur wrestling and go to college. Then Grey went to see Boris Malenko at his gym that didn’t have mats, and was really set up for judo students. Malenko scoffed at Graham’s suggestion, since Graham himself never even finished high school, and offered to show Grey some things. But training and a proper education didn’t mix, so he only went a couple of times.

“I was still in high school and it was 100 miles to go from here to him twice a week, and there was no way I could do that and go to school. I didn’t have a car at the time,” recalled Grey. Yet he knew that he could make it, judging by what he saw at Malenko’s Tampa gym. “It was a lot of small guys; I was bigger than them, and I was only 16.”

Closer to his school, Louie Tillet was running Sunbelt Wrestling, in opposition to established Florida promoter Eddie Graham. With a TV show, Sunbelt had the likes of Austin Idol, Jimmy Valiant, Thunderbolt Patterson, Bob Roop, with Buddy Landel as Roop’s brother Buddy; the great villain Great Malenko still wrestled, while his legitimate sons, Joe and Jody Simon, were the babyface Simms brothers (and down the road were Joe and Dean Malenko).

Grey trained with Tillet in Jacksonville at a small training school that was not really publicized, in a day when kayfabe was still strong. “He trained us for a couple of months. I didn’t wrestle,” said Grey. The teenager went twice a week for two or three months before being allowed to wrestle.

What Grey didn’t understand at the time was all the politics going on. Tillet was running opposition to Graham’s Florida Championship Wrestling, an NWA-affiliated promotion. Therefore as a rebel promotion, Graham and his colleagues set out to put him out of business. Tillet’s main place was the American Legion Hall in Orlando on Fridays, as well as other places in Florida, while Graham ran on Sunday at the Eddie Graham Sports Stadium in Tampa. Then Graham started stacking the cards with names from the other NWA affiliates — and running on Fridays too.

With Sunbelt out of business, Tillet was fortunate to have an ally in Ole Anderson, who went against the wishes of the other NWA powers-that-be, and hired Tillet as an assistant promoter in Atlanta.

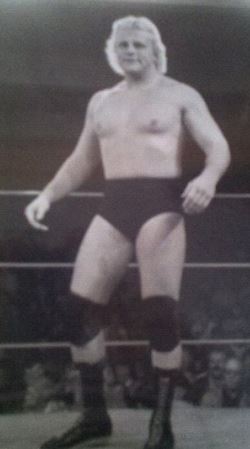

An outfit that Jerry’s mother made for The Golden Boy.

Tillet got work for his young charge, even if Grey was way out of his league. The match was in Atlanta. “My first match up there was against Ernie Ladd,” recalled Grey like it was yesterday. “Louie trained us pretty stiff. They didn’t really smarten us up all the way, either, because back then, it was just different. I didn’t really know if it was all the way a work or a half-shoot or whatever. I asked what was going to happen when we went out there, how do we know who’s going to win? They didn’t even tell us that until I got to TBS. All of a sudden, Grey was surrounded by some of the top names in the world: Harley Race, Dusty Rhodes, Roddy Piper on commentary, Ric Flair just before he won the NWA World title for the time.

The giant Ladd towered over Grey, and Grey had to learn quick, but not in the way one might think. “He poked me in the eyes and didn’t even come near me, so I’m like, ‘Oh my God! I’ve got to sell? He didn’t even touch me.’ He was so easy. Then I found out, okay, this is how some of the guys are. Even though he was so big, he was so easy.”

From there, “The Golden Boy” Grey figures he worked 3,000 matches during his career. He listened and learned, and became an excellent hand in the ring. “Wrestle experienced guys, that’s how you learn,” he explained, citing Dick Slater and Bob Orton Jr., as two influences.

But there was learning outside the ring too. Grey left the expanding Superstation world to return to Florida to work for Eddie Graham, but that almost didn’t happen. Grey made the deal to go to Florida through assistant booker JJ Dillon, who was working under Dory Funk Jr.

“I didn’t realize how mad Eddie Graham was at Louie Tillet for going against him. He didn’t like Malenko either,” he said. “They liked me at first, because I was young, big, good build. They said, ‘Who trained you?’ Eddie Graham, that was the first thing he asked me. He liked me really good. ‘You were good. Did you wrestle amateur?’ ‘Oh yeah.’ ‘Good, good.’ Then he goes, ‘Who trained you?'”

“When I said, ‘Louie Tillet,’ I could just see that he wanted to kill me. Then he made me pay some dues. It was just as bad as going to Matsuda’s tryouts, they called it, where they broke Hogan’s leg. They did the same thing. They put me in the ring with Haku, Tonga they called him then, King Kong Tonga, and told him to hurt me. They must have, because he did every kind of martial art he knows. I thought, because Louie trained us stiff, so I thought that’s the way it was, so I was fighting him back. He was really getting mad then. And you know how tough he is. So he was really getting mad then. I guess they liked it that I fought back at least, and I didn’t quit. Especially when I came back to the dressing room, and I asked them where I could wrestle next. Eddie Graham just looked at me like I was crazy. … so then he liked me a little bit.”

The key for Grey was when Dusty Rhodes took over the book in Florida. “He liked me good. He put a mask on me and started pushing me a little bit, the Destroyer. I asked him if I could go on the road and work full-time, because I was just working a couple of times a week.” Rhodes arranged for Grey to head to Mid-Atlantic, based in Charlotte, where he could work full time.

“It was the best thing to happen,” said Grey.

He was already friends with second-generation up-and-comer Jake Roberts, and The Snake offered Grey a place to crash. His roommate already was Gene Anderson, who worked in the office, but still wrestled a little. “That was like the odd couple for sure,” marveled Grey, who lived with them for eight months, but learned an incredible amount.

“Jake, he had a good mind even then, and Gene, of course, so I learned really good. I was with them all the time, making trips with them all the time. That’s where I really learned a lot, riding with Jake every day, and Gene Anderson. They told me everything. I thought you were just supposed to go in there and do moves and moves and keep going, doing fast moves, non-stop. I didn’t realize the psychology and all that until they started talking. ‘It doesn’t matter how many moves you do, it’s when you do it.’ That’s where I learned the most, guys like that telling me, driving down the road.”

From there, Grey was a road warrior. He spent time in Mid-South, Florida, numerous trips to Japan, Puerto Rico, the Pacific Northwest, and World Class at its peak. It was in Texas where he got what he feels is the all-time greatest praise, from Skandor Akbar and Fritz Von Erich. “The biggest compliment was when they told me I looked like a young Johnny Valentine because I would get a front facelock and just stand there. They told me, ‘Just look at the people mean.'”

Jerry Grey in Portland.

His best-known moment was working against “Haitian Sensation” Tyree Pride, trading the Florida Bahamas title in 1986.

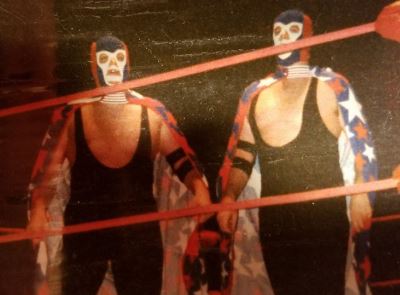

In Oregon, he teamed with Tom Prichard in 1984. “We were the tag team champions for a long time up there,” he said. Another team from 1987, with Bob Cook, under masks as the Masked Yankees, don’t get the credit they deserve, said Grey. “We were really the last tag team champions in Florida history, but they lie in whomever makes up the history, when they say that Steve Keirn and Mike Graham beat us in some town they made up … we were the tag team champions and Crockett took over Florida. The Yankees were champions and they were going to bring us to WCW and everything, but I didn’t want to go because I had Japan, I was going a lot to Japan, It was better to go there and make the same money and be off a lot too. So one night we had the belts with us in Daytona, the Ocean Center, a huge place, 10,000 and Flair didn’t show up or something happened with Flair, and they said, ‘We have to make the people happy and let somebody win the belts.’ They just said, ‘Give us the belts.’ They did ask us to give them the belts, but not have a match. Then they just acted like Steve Keirn and Mike Graham won them. It was weird. The match never happened.”

The Masked Yankees (Bob Cook and Jerry Grey).

When the Florida promotion shut down, Grey saw an opportunity and started promoting shows in 1988, using the WPW name. His connections meant that he could bring in big names like Terry and Dory Funk Jr., and Blackjack Mulligan and his sons, Barry and Kendall Windham, for cards. He always made sure to pay the big stars up front when they arrived so positive word spread. After all, Grey had been there too. “I made sure they got their money right when they walked in the door, usually, because I know how it feels to sit there and wait, wondering if you’re going to get money.”

The transition to mostly paid shows made sense and Grey ran with it, seeing the country once again.

Married and divorced twice, Grey doesn’t have any children, but he has an extended family through professional wrestling and is relying on them when times are tough. His colleagues appreciate him in one extra aspect: “Thank God I have a good memory, because I tell some of the guys and they don’t remember these stories.” … they said, “Keep telling me stuff, because then I remember them!”

RELATED LINK