Jim Ross’s Slobberknocker is one of only a few wrestling autobiographies that it’s not overstatement to describe as “eagerly awaited.” Ross is a familiar presence to at least two generations of wresting fans. Working at both World Championship Wrestling and the World Wrestling Federation during the 1990s, he was at the height of his career during wrestling’s most lucrative era. For fans who were introduced to wrestling during the Monday Night Wars, his voice is as intimately associated with their love of wrestling, and likely their childhood, as the voices of announcers like Gordon Solie and Lance Russell are for fans from who grew up in the 1970s and early 1980s.

Unlike Solie and Russell, though, Ross has been involved with the business of wrestling at almost every level. He’s swept floors, set up the ring, refereed, and driven wrestlers between towns. He’s also been responsible for negotiating syndication deals with local affiliates and signing and developing talent. Though he wasn’t in the driver’s seat as pro wrestling went mainstream, he was sitting close enough to the people driving to know how it all really went down.

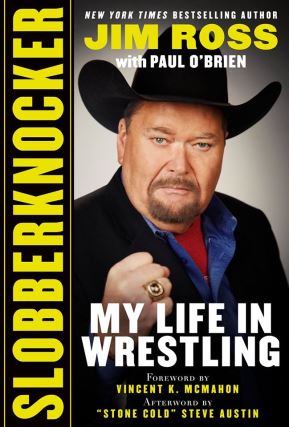

Thankfully, Slobberknocker delivers on what most fans will be expecting. If you’ve seen Ross live as part of his one-man show or listened to his podcast, you have a sense for his folksy storytelling charm. It translates well to the page and it shouldn’t be surprising that Ross opts for a style that is straight-ahead and free of overheated hyperbole. Working with co-writer Paul O’Brien (his initial collaborator, Scott Williams, died unexpectedly in 2016), he delivers one of the best-written wrestling memoirs in memory.

With his long career and the variety of positions he’s worked in, Slobberknocker has a lot of ground to cover. It is a consistently fun read that zips through almost 50 years of Ross’s life. He dedicates roughly half to his work in the regional territories of the ’70s and ’80s, and half to his tenure at World Championship Wrestling and the WWF in the 1990s. Fans who feel a particular affection for either era won’t be disappointed.

Ross grew up as an imaginative boy in rural Oklahoma and fell in love with wrestling through television. “I was immediately drawn to wrestling,” he writes, “because the action usually followed the same rules as the movies I loved so much.” He combined his childhood love of books with a love of sports as he developed a talent for sports analysis. “I wasn’t blessed with the ability to work with my hands like my father and grandfather,” he writes. “I didn’t have their natural size or ability as a farmer or hunter. I even felt a little guilty about that as I was growing up. But one thing I did have was the ability to talk.”

After burning out following only a single semester at Oklahoma State University, Ross was introduced to the wrestling business through a job babysitting aging promoter Leroy McGuirk. He parlayed it into an announcing position that grew into a close working relationship with McGuirk’s business partner and Ross’s eventual mentor, Bill Watts. Last guard regional wrestling promoters like Watts, McGuirk, and Jim Barnett, and talent like Skandor Akbar, Danny Hodge and Harley Race make several appearances in the first half of Slobberknocker. A lot of younger fans experience these names like dusky shadows but Ross knew and worked alongside them. It’s a pleasure to see them take so much of the focus of his book and his affection and respect for many of them is clear.

Ross was soon making six figures as an employee of Watts’s Mid-South Wrestling. Through Watts, he developed into an earnest, affable announcer in front of the cameras and a savvy businessman in his own right behind it. Stories of road trips with McGuirk and buffet dinners with Ernie Ladd give way to Ross’s negotiating the multi-million dollar deal that saw Jim Crockett Promotions absorb Bill Watts’s Universal Wrestling Federation. “I came in as a gopher,” he writes, “taking notes and buying cigars and whiskey for Leroy — now I found myself on a private jet, just me and the pilot, as I made my way to MillionAir hangar in Atlanta.”

By the end of the 1980s, Ross was working for Jim Crockett when Ted Turner purchased Crockett’s promotion. Ross’s face and voice were soon being broadcast internationally through Turner’s TBS cable channel. After being brought in as an employee of TBS, Ross found himself working as an executive out of an office in Atlanta’s CNN Building. It must have been a head-spinning ascension but Ross relates it all with his easy charm.

He was able to transition to the WWF by the early ’90s and into the role that would bring him his widest fame. On-camera he was announcing WrestleMania. Off-camera he played a major role in developing Mick Foley, Steve Austin and Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson into the biggest wrestling stars of the decade.

Ross dishes a moderate amount of dirt about the people he’s worked with. It’s maybe less than some fans would like given how well-travelled he is and his relationships with many of the people most responsible for wrestling’s development over the past half century. It’s a minor complaint, and not necessarily a complaint at all. Ross did his share of drinking combined with some light drug use, but he seems to have mostly kept his partying from taking over his life. He has few axes to grind, seems comfortable with his place in wrestling, and comes off as uninterested in relitigating the past.

Even widely derided figures like Turner-executive Jim Herd come off as more misunderstood than buffoonish (Ross calls him a “truly decent man who had some ill-advised ideas”). Ross’s even keel keeps the narrative from getting bogged down. It frees him up to write disarmingly thoughtful and deeply personal passages about his relationship with his parents, his losses in business, his three marriages and relationship with his children, and his struggles with prescription drug abuse, panic attacks, and Bell’s Palsy.

It’s bad enough, for example, to imagine coping with the physical side effects of Bell’s Palsy when your living is made off of your voice and appearance. It’s another thing altogether when imagining your boss as someone who considers sneezing a sign of weakness. “I didn’t want to look him in the eye because of how my face was,” Ross writes about seeing Vince McMahon after his second attack of Bell’s Palsy. “I didn’t want him to see weakness. I didn’t want him looking at me and thinking I couldn’t do a job for his company.”

Ross, of course, never stopped being able to do his job. It’s this ability to persevere, coupled with an openness that Ross developed with age, that readers are most struck by. Mentions of a second book that would focus on the last two decades of Ross’s career have already been floated in several interviews he has given. If it builds on the foundation he’s laid with Slobberknocker, it would be a welcome read.

RELATED LINKS