“It’s all about the performance; it’s not about winning or losing.” Those are words that wrestling veteran Kevin Jefferies has lived by during his over 30-year career in professional wrestling. His love and passion for professional wrestling are readily apparent to any that have met him.

Originally from Vancouver, Jefferies grew up in Kelowna, British Columbia. He loved watching wrestling as a little boy. “I swear to God I can remember back to when I was four or five years old watching it on TV, every Saturday, All-Star Wrestling out of Vancouver. Back then I thought it was all real. I really thought they were beating on each other and hated each other.”

Jefferies’ athletic background consisted of high school track and field, and amateur wrestling. However, all he really wanted to do was be in a wrestling ring. Jefferies would later get his chance at the age of 17 when he started with All-Star Wrestling in Vancouver. At first he would hang out at events, picking up jackets and setting up the ring with Roy McClarty and Sandor Kovacs. Then Total Entertainment out of Kamloops asked Jefferies to promote shows in the interior towns of British Columbia. “I was the front man. I would do the promotion and all the radio interviews. That’s how I started.”

During this period, McClarty, who was the referee with All-Star Wrestling, and set up the ring in each town, took Jefferies under his wing. “Roy was like my dad on the road. I never had a father. My mom raised seven kids all by herself. He taught me a lot about about the business, a lot about how to save your money, how to live, and how not to let people take advantage of you. He taught me a lot about life. He taught me how to referee and the wrestling. It was great.”

Jefferies started refereeing at first and would go into the ring earlier in the day to fly around, until one day McClarty took notice of his unbridled enthusiasm and asked him the fateful question — would he like to wrestle professionally?

“[Roy] said I had the biggest smile on my face like it went from one end of the arena to the other. So he showed me stuff. He taught me the ins and outs. It was great.” Jefferies was and still is extremely grateful to McClarty and his family for enabling him to live his dream.

The training with McClarty consisted of going into the ring and learning the basics. “I was a flyer, I liked to be on the ropes and moved around and all that. Roy would try to settle me down; well, you know the old school way was a headlock, drop down and hold the headlock for 15 minutes and the fans went nuts. Get up, do some more moves, and then go again.”

What was impressed on Jefferies was learning all the basics and learning how to sell. “Telling a story was the most important thing, telling a story to the wrestling fans, and I’ve always said if you show wrestling fans a good story and you show them a good match, no matter whether you win or lose, those fans will remember who you are. You’ll walk down the road and they’ll remember you right away.”

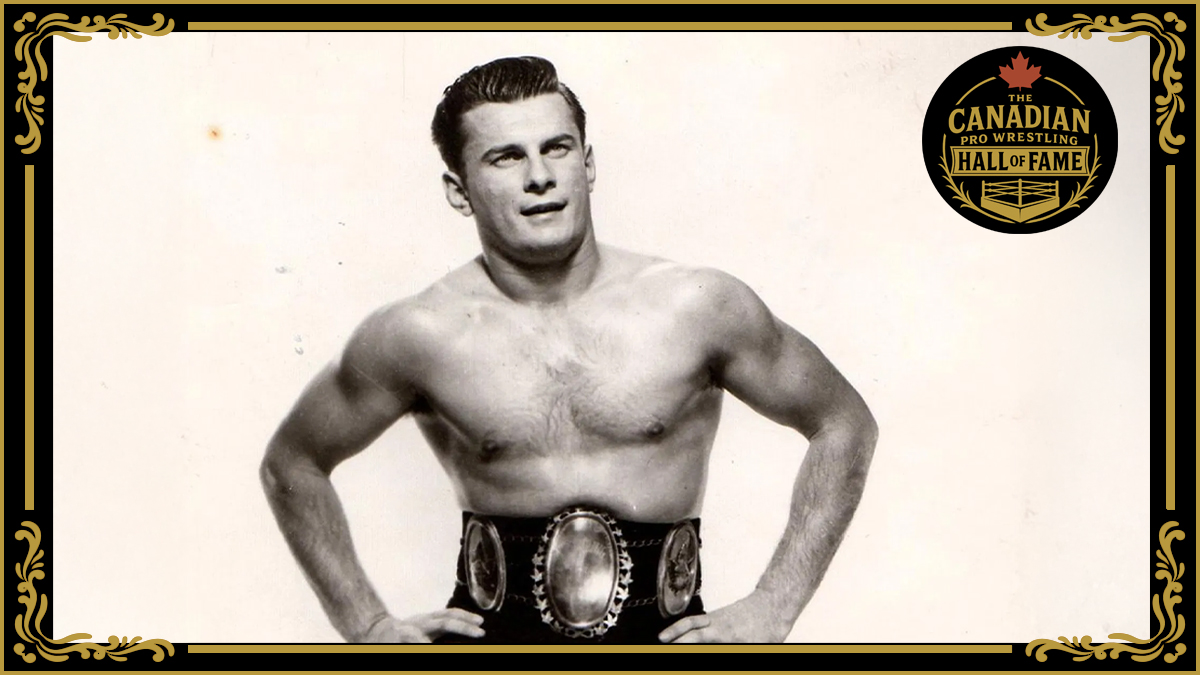

In the gym, Jefferies focused on ensuring that he could build up his stamina in order to be able to perform in the ring, but that he was never a bodybuilder type. During his days as a wrestler, the biggest Jefferies wrestled at was 205 pounds, but he felt most comfortable at 180 pounds due to his 5-foot-7 frame. With his brown hair and green eyes, Jefferies captured the attention of fans when he stepped into the ring as the babyface hero. For much of his career, he wrestled and refereed usually clean shaven or with a moustache.

As a wrestler, Jefferies never had an exclusive finishing move he used for ending a match, but a favourite was a sunset flip out of the turnbuckle. To set up the flip he would usually do a drop kick off the top rope first. His opponent would typically reverse him, giving Jefferies a smash into the turnbuckle, after another one, Jefferies would shoot his legs up high and roll him over. Part of Jefferies’ enjoyment of using the sunset flip was the smoothness of how it was executed.

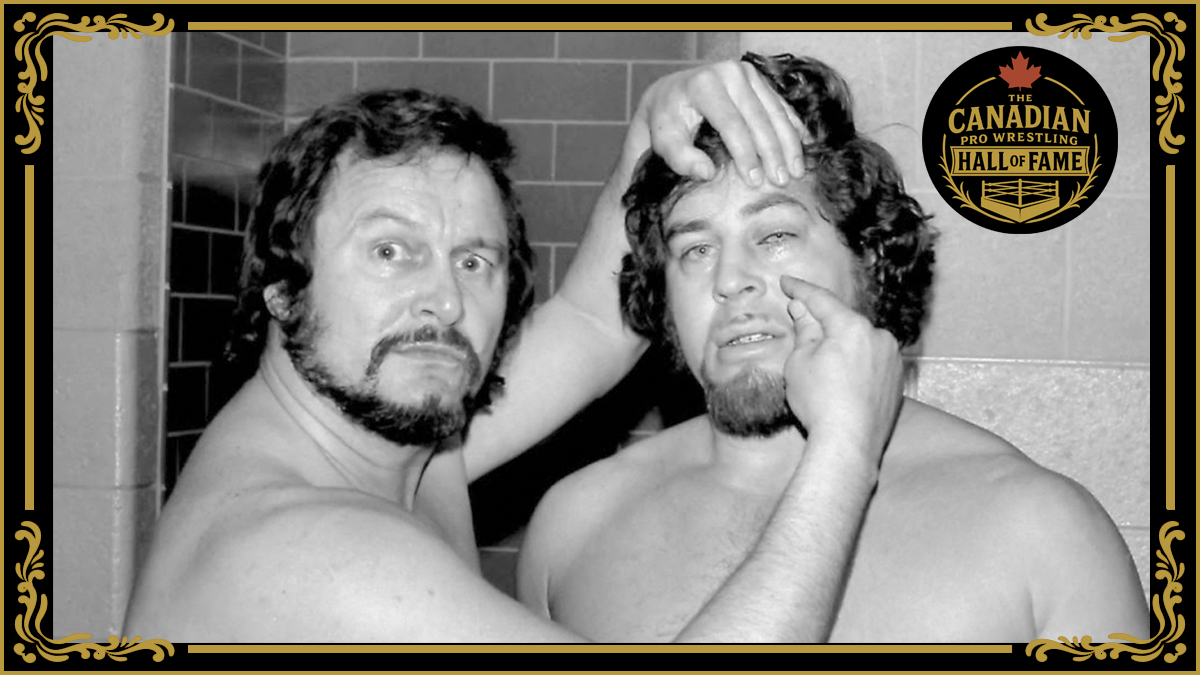

During this period of Jefferies’s career “kayfabe” was still prevalent, where the heels and babyfaces were kept separate to maintain the illusion with the public that they hated each other. “It was kind of fun trying to fool the people. I miss the old school wrestling so much.” Jefferies felt it gave professional wrestling a greater sense of believability and unpredictability that is missing nowadays.

To give some idea of how much the public believed wrestling was real, Jefferies cited one particular story involving his late Aunt Kaye. “She used to come see me wrestle at Exhibition Gardens in Vancouver. One night Terry Adonis is beating the heck out of me. They’re carrying me out on a stretcher when Adonis kicked me off it. Well, my aunt chased Adonis all around the ring with one shoe on and one off all the way back to the dressing room!”

The planning involved in being a wrestler versus being a referee was quite different, but Jefferies found he was adept at both roles. Prior to wrestling in the ring, Jefferies would chat with his opponent to address a few high spots. Then they would go out and call the rest of the match in the ring. For refereeing he would ask the wrestlers what the finish was for the match, and if there was going to be any interference that he had to be involved in. During his time with WWE, when he had three or four matches to referee a night, he would have to recite what the finishes were to road agents Jay Strongbow or Gorilla Monsoon. Later in the evening he would check to see if there were any changes. However, as a referee he had one other role: he had to pay attention to the crowd reaction during the match. “A lot of the times when I have officiated in the ring, and I’ve found the match to be very boring, I’ve gone over to the guys and said, ‘You have to pick it up a bit.'”

The role of a referee is one that is often underestimated, but it is a vital according to Jefferies. “Without the referee the match could be horrible. You just have to use your brain to know when to turn and when not to turn. Know what the counts are. It doesn’t come easy to a lot of people. I’ve always said as a referee you’re like a cop in the ring, you’re in charge.”

As Jefferies’ career progressed he got a call from Keith Hart who asked him if he would be interested in promoting Stampede Wrestling in British Columbia. Jefferies readily agreed and became the front man for Stampede Wrestling in the province. “So I started with that, then they would use me in the ring, and when the midgets were out there they would put me in mixed tags with the midgets. I would have singles matches too.”

As he reminisced, Jefferies relayed a particularly funny story involving Stu Hart and one of Hart’s vans. “We were doing a big show in Vancouver. Dynamite Kid, Davey Boy Smith, Stu Hart, and I were flying in and Stu Hart’s van was picking us up at the airport. Dynamite Kid opened the sliding door and it fell right off. We just pissed ourselves laughing. We’re sitting in the van and of course it’s a cool, cold, and damp winter day. Stu Hart asks the guy driving the van if the heater is working and the driver says that was the only thing that worked in the van! It was just hilarious.”

Yet, what Jefferies feels the most for Stu Hart is gratitude and respect. When Hart sold Stampede Wrestling to WWE, Jefferies returned to Kelowna because the promotion had shut down. “Three to four months later I got a phone call from the WWE. I started refereeing for them thanks to Stu putting in a good word for me about my officiating in the ring.”

Matches Jefferies remembers fondly are the team-ups with midget wrestlers Cowboy Lang and Coconut Willie, against Little Tokyo. “There were some mixed tag matches that were unbelievable, so many high spots. I used to travel a lot on the road with them and refereed their matches.” Jefferies commented that a lot of midget wrestling is nonexistent now. “You still have the midgets wrestling, but not too many territories bring them in anymore. WWE tried it at different points, but Vince McMahon was always for the big boys.” Jefferies went on to elaborate that the reason might be traced to the Little People organizations all around the world. “The name ‘midget,’ they don’t like and they’re against taking a little person and making a fool out of him in the ring; but Little Tokyo always said, ‘I’ve got to make a living too.'”

Jefferies’ memories from his time in the WWE in the 1980s were pretty memorable due to its popularity at that time. “To be able to walk out to the ring and see the building packed with 20,000 or 30,000 people your adrenaline just popped.” A particularly memorable match was one he refereed between Hulk Hogan and King Kong Bundy on Saturday Night’s Main Event. “Those were the fun ones. Someone threw a beer bottle and it flew right by my ear and King Kong Bundy’s ear. It scared the living heck out of us.”

Another significant figure whose matches Jefferies refereed was Andre the Giant. When Tim White wasn’t available to be with Andre on a particular night, Jay Strongbow would ask Jefferies to go with him. Jefferies first met Andre prior to his time with the WWE when he was still wrestling out of Vancouver. It led to one of his more interesting stories involving The Giant. “We all went downstairs to the Blue Room night club in the Plaza Hotel in Kamloops. We’re all drinking and Andre is buying the beers. They’re bringing it over by the case. I say it’s my turn to buy. Well, Andre says, ‘No, I’ll get it,’ slaps me in the chest and I go flying three feet back. It gets to after last round. Andre calls the waitress over and asks for another round. Well, the waitress says she can’t. The bartender/manager came out and says in a loud voice, ‘What’s the problem?’ Andre stood up. The bartender nearly died of fright. Andre took his little finger, tapped the middle of the table and repeated his request. The bartender — scared to death — gave us one more round. Andre goes to give him the money and he refuses the money. Andre slams his hand on the table. The bartender says, ‘What’s wrong?’ Andre says, ‘You should have done it at the beginning of the night then everything would have been free.'”

The reason that the 52-year-old Jefferies had to stop refereeing was ultimately because his eyesight diminished and he needed glasses; it was considered too dangerous to continue. However, since then he has had laser eye surgery, and a knee operation, and has started doing special refereeing for local promotions in British Columbia.

Nowadays, living off his investments in Kelowna, one of his most rewarding roles is that of a mentor for the younger generation of wrestlers coming up. “I show young guys techniques in the ring and help them out with the finishes. A couple of the territories like All-Star Wrestling and Thrash. As long as they listen, I enjoy showing them stuff and watching them perform it in the ring. I’m here to help them improve if they want it.”

Of those Jefferies has enjoyed working with in recent years he lists Kyle Sebastian, Adam Ryder and in particular Vance Nevada; and those feelings are reciprocated by Nevada: “Kevin Jefferies may be one of the unsung heroes of Canadian wrestling. It was a thrill to not only have the opportunity to meet Kevin after knowing so much about his career, but to also have the opportunity to share a ring with him,” said Nevada. “He has refereed one of my matches — against Kyle Sebastian, and he’s truly a class act in my book.”Jefferies considers Sebastian a true a friend and if there is anyone he wishes he could have a match with today it would be him. Sebastian has had many kind words to say about Jefferies as well: “Kevin Jefferies has been a great help to me. He’s watched and critiqued every match I’ve asked him to. He has an eye for the littlest things that will help my career in the future.”

For the future well-being of the business, Jefferies hopes that more people start to go to the independent shows. “If a lot of the people who watch WWE started going to the independent shows, I really believe they would get hooked on it. These guys are going out there and putting on tremendous performances for a $10 or $12 ticket. It’s amazing what some of them can do. It’s sort of the old school and the new school wrestling.”