Before The Rock was The Scorpion King, before Rowdy Roddy Piper wowed us in They Live, and before Hulk Hogan took on Rocky, a man named Bull Montana starred alongside the entire A-list of Hollywood. But it was a different Hollywood — the Silent Screen Hollywood of the 1920s. He found fame in the ring and on film, and was recruited by one of the biggest stars of the day.

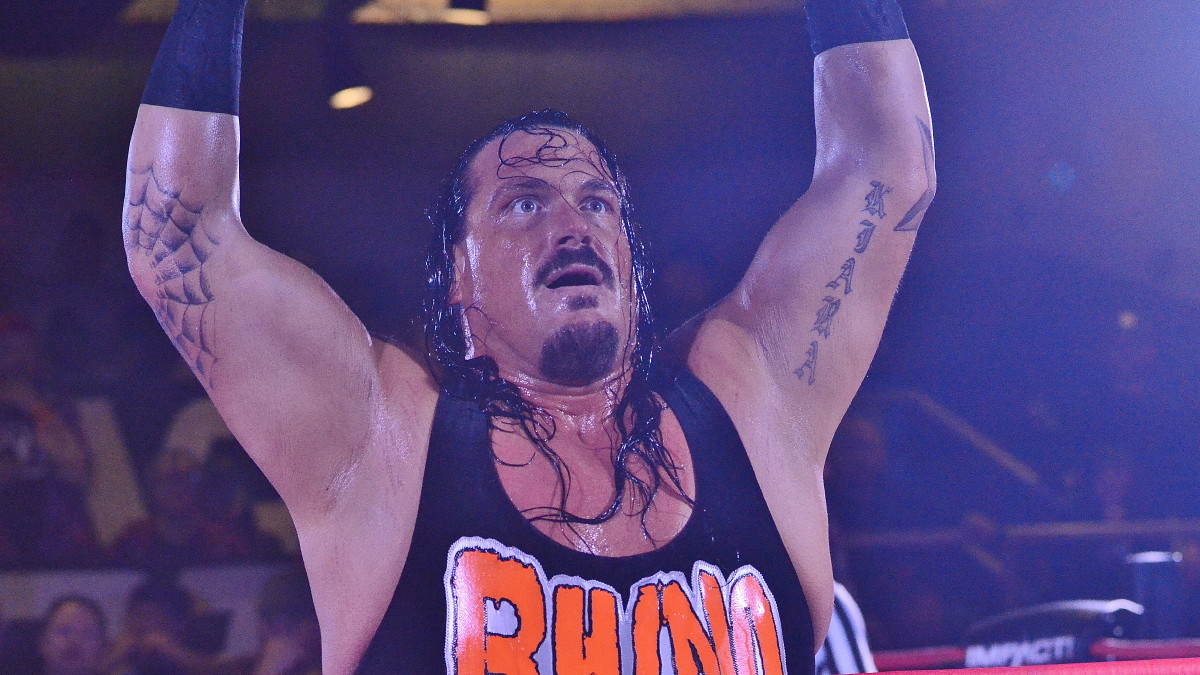

An autographed, widely circulated publicity shot for Bull Montana.

Born Luigi Montagna in Voghera, Italy, on May 16, 1887, he was a wood splitter in the old country for seven cents a day before coming to America for a better life, according to a 1939 newspaper article by esteemed sports columnist John Lardner. Montagna eventually found his way into the old carny wrestling circuits of New York and New Jersey, near where he lived. He was re-Christened “Bull Montana” at a wrestling event in Coney Island, given the character of a big, burly cowboy, according to a report from the Galveston Daily News in 1930. Kayfabe was so strong at the time that he was given a hero’s welcome when he came to wrestle in his “home state” of Montana.

In a 1928 story in the Montana Standard, Montana addressed his start, his colourful vernacular caught by the writer. “A feller asked me to fight in New York one night and offered me five dollars. I needed dat finiff and I said I’d fight anyone he introduces me as ‘Bool Montana, de cowboy middleweight champion of de West.’ Say I hadn’t seen a cow since I left Eetaly. But I was a champion of de West all right. I lived on de West side of New York and I was champion of Bleecher street.”

Wrestling at 180 pounds as a middleweight and lightheavyweight — when those terms weren’t a knock — Montana did get into the ring with top stars like Frank Gotch, Stanislaus Zbyszko, Ed “Strangler” Lewis and Jim Londos.

His entry into Hollywood was far more phenomenal than his entry into wrestling: Montana wasn’t discovered by some mere talent scout. “Douglas Fairbanks persuaded him to try his luck in Hollywood, and gave him supporting roles in a number of his popular films in the teens,” the Heavyweight Champion of Film Critics, Entertainment Tonight‘s Leonard Maltin, tells SLAM! Wrestling in his first-ever interview discussing professional wrestling films and actors. Fairbanks, who was one of the most popular actors in the Silent Film Era, did not work with just anyone. Fairbanks was one of the greatest action stars of early Hollywood.

Montana’s success did not end with Fairbanks. “He also appeared in two major hits starring Rudolph Valentino, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921) and Son of the Sheik (1926),” Maltin points out. Valentino, who made more girls swoon then than Brad Pitt and Justin Bieber combined could today, provided the perfect contrast in these films to the rugged Montana, who always acknowledged that his face was his fortune, and that his cauliflower ears and crooked teeth helped him stand out.

And, like Pitt and Bieber, Montana got a fair bit of press, both good and bad. In 1928, he was in the news for having Jackie Laverne, who he claimed was his housekeeper and she claimed was his wife, jailed on a charge of battery. A year later, his proper marriage to Mary Paulson Montana at Bull’s Hollywood home was news fodder as well. Time Magazine got in the act when they split in 1931: “Divorced. Louis (‘Bull’) Montana (real name: Lugia Montagna), 44, wrestler and cinemactor; by Mary Poulson Montana; in Los Angeles. Mr. Montana admits his face frightens women and children. Mrs. Montana said she was afraid to live with him.”

Playing a villain finally led Montana to star alongside one of the greatest actors in the history of cinema, “The Man of a Thousand Faces,” Lon Chaney, in director Maurice Tourner’s Victory, based upon a Joseph Conrad novel. Chaney, who was known for playing villainous characters such as The Hunchback of Notre Dame and The Phantom of the Opera, is upstaged in the small but brutal role that Montana plays in Victory.

His professional wrestling experience must have taught him well, however, as Montana realized that he could not survive in Hollywood as a heel forever. “He apparently had a sense of humor about himself and … starred in some silent comedy shorts,” Maltin reveals. After his long run of playing villains, Montana then “appeared as a ‘heavy’ opposite such great comics as Buster Keaton and Charley Chase.”

Bull Montana and French boxer turned entertainer Georges Carpentier.

Montana’s most famous wrestling bout was even more of a work than usual. Having befriended ex-heavyweight boxing champion of the world Jack Dempsey in The Manassa Mauler’s film debut, 1920’s Daredevil Jack, the duo teamed for a 1925 special exhibition in connection with the U.S. battle fleet’s athletic day at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. “The two celluloid artists attacked each other with convincing fury, scorning custard pies and other studio weapons and battling with their bare hands,” reads an account dug up by wrestling historian J Michael Kenyon. “Dempsey finally heaved the Bull through the ropes after ten minutes of what was called wrestling and was conceded the victory.”

What also sets Montana apart from other actors in film history is that he survived the radical change from silent to sound films. Many actors who thrived in the silent cinema found their careers end when their voices did not appeal to Hollywood producers. Even the man who brought Montana to the silver screen, the legendary Douglas Fairbanks, did not survive the transition to sound. Montana should be remembered by film historians for being part of this elite club, as well.

But surviving the transition to sound films wasn’t entirely easy for Montana, Maltin tells SLAM! Wrestling. “Although he continued working into the sound era, there wasn’t as much opportunity for ‘types’ like Montana, and he may have had an Italian accent, which would have limited his casting opportunities. But producers still called on him when they needed a muscular type who didn’t have lines, as in Flash Gordon (1936).”

Starring in the Flash Gordon serials further cements Montana’s legacy in Popular Culture, being part of the franchise of one of the most popular comic book adaptations ever made. In professional wrestling history, Montana, therefore, is the first wrestler to appear in an American comic book film.

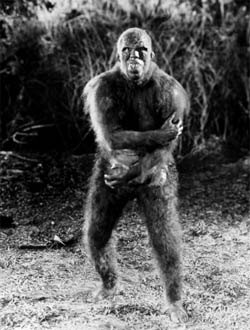

Montana as the ape-man in The Lost World.

For these, and many other achievements, Montana deserves to not only be remembered, but celebrated, by both film and wrestling historians. His 30 years in professional wrestling paved the way for Montana’s entrance in to Hollywood, and seems to have taught him much about surviving in the scandal-plagued early days of Hollywood.

Where the transition from Silent to Sound films, or the vicious culture of early Hollywood couldn’t get him, heart disease eventually did, according to a UNS Wire Service report; he died January 24, 1950 at French Hospital in Los Angeles at 62 years of age.

Maltin, who still edits the annual Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide, bemoans the fact that Montana is not better remembered for his achievements. He encourages SLAM! Wrestling readers to watch Montana’s films. When asked which one his favourite is, he mentions one that influenced one of the highest grossing films of the 1990s: “I think of him, first and foremost, as the menacing ape-man in The Lost World (1926), a classic silent feature that predated King Kong and set a template for adventures about prehistoric beasts that continues right up through Jurassic Park.”

RELATED LINKS