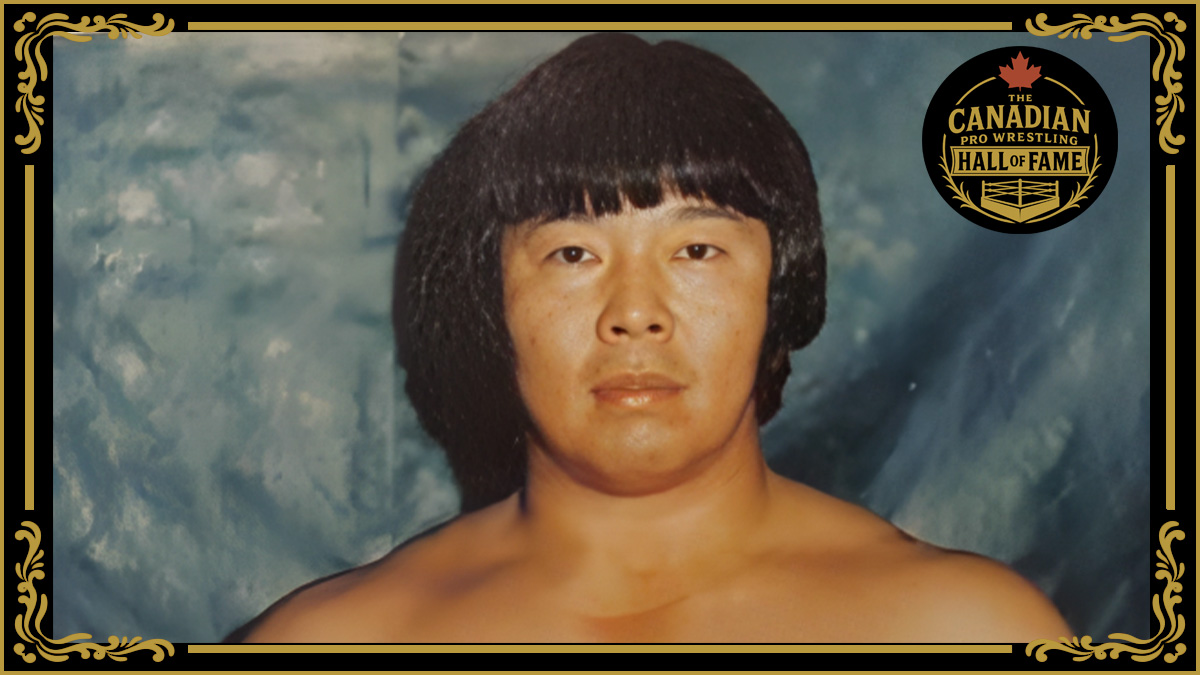

The sound of the tomato cans called to Dean Higuchi. That’s right―tomato cans.

Growing up as a teenager in Honolulu, Higuchi was fascinated by the clanging of makeshift weights hoisted by a fireman who lived in a nearby boardinghouse. Every afternoon, the noises rang out, and Higuchi listened and watched in awe.

“I’d jump over the fence and watch the guys do their thing. They had little dumbbells, not like they had today,” he recalled. “They were made of gallon cans on each end, like a tomato sauce can on each end of the bar, and they would fill them with concrete, wait for the next day, fill the other side, and now they’ve got one dumbbell. And that was it. I’m not kidding you. Talk about caveman days.”

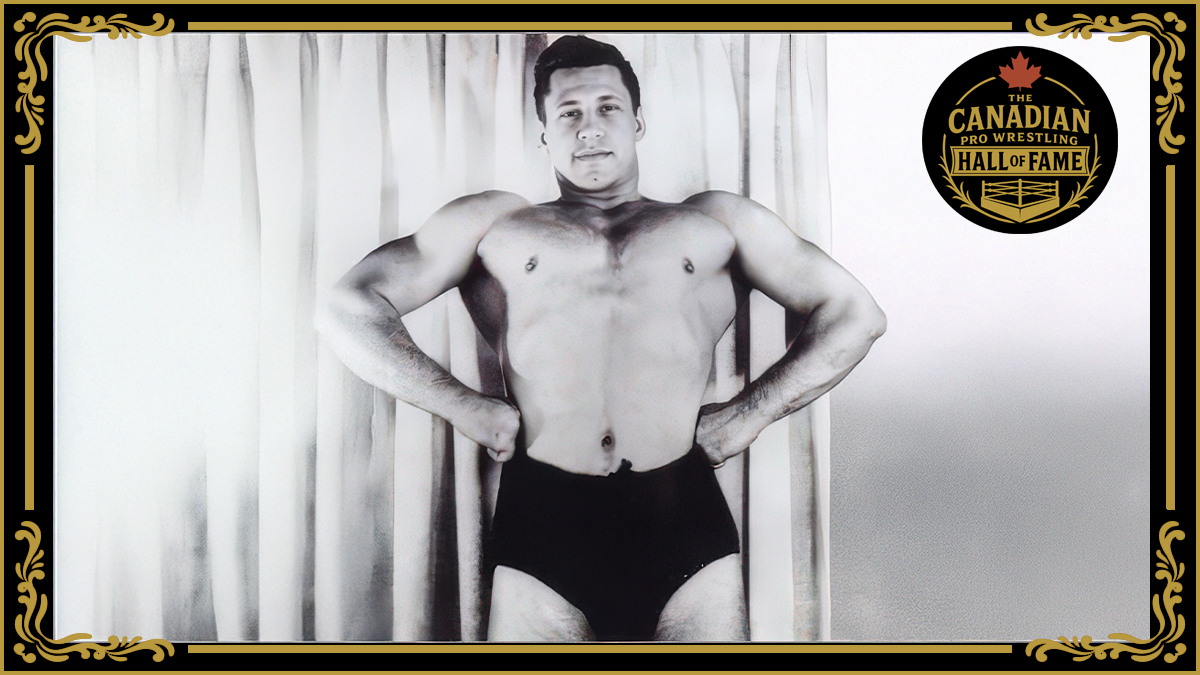

Forget the instructional DVDs and the infomercials for high-priced resistance strength equipment. One of wrestling’s best physiques was built on a solid foundation of household throwaways.

“We had no inkling of how much we were lifting,” said Higuchi, who started pumping iron, er … tin, around 1950. “The fireman just said, ‘Here, go lift the big heavy one. Take these.’ That’s all. We didn’t know.”

Higuchi is one of the honorees at the Cauliflower Alley Club Reunion this week in Las Vegas, where he will be recognized for parlaying his bodybuilding prowess into a quarter-century career as a fan favorite inside the ring.

In deep, expressive tones from his home near Vancouver, Higuchi explained that weightlifting was viewed with something of a jaundiced eye, even in Hawaii, where he captured the Mr. Hawaiian Islands title in 1956. He also placed sixth in the Mr. America physique contest that year.

“Everybody that did lift weights was kind of hush, hush. You were ribbed a lot. Guys would call you Sampson or Tarzan,” he said. “But I enjoyed it. It wasn’t a team sport. It was like anything else. The more you put into it, the more you got out of it.”

Higuchi made fitness his full-time job in 1957, when he opened a gym on Kalakaua Avenue in Honolulu that quickly became a regular stop for wrestlers passing through the area on the way to Japan.

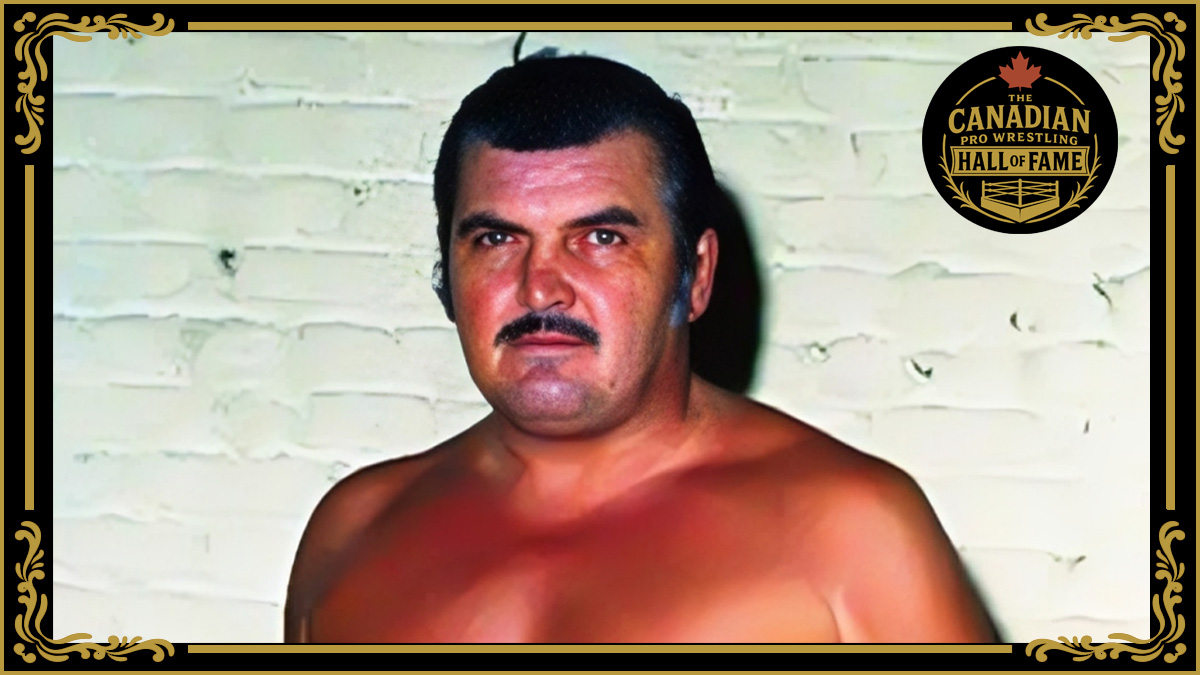

Don Muraco exercised there as a high schooler, and Larry Pitchford, better known as Beauregarde, and Jimmy Snuka were other workout rats. But colorful Ripper Collins, who tended to be on the doughy side, stands out in Higuchi’s memory for boosting business at Dean’s Gym.

“Nobody gave me a plug on TV but Ripper Collins. He was the only guy, and the way he did it was he’d knock it. He’d say, ‘If you want a body like mine, don’t go to Dean’s Gym; otherwise, you’re going to look like all these guys. If you want a body like mine, this is it.’ So it would work in reverse. I thanked him for it.”

Surrounded by all those pros, Higuchi decided to make the transition from to the mat in 1962, thanks in large part to Dick Beyer (The Destroyer), who worked with him on off days in a ring at the Civic Auditorium in Honolulu.

“He spent a lot of time, precious time that he could have been with his family,” Higuchi said. “I owe my experiences to him. The guy was great, showed me everything and then some. He’s the reason I was able to start to make some money in the business.”

As for conditioning all those muscles, Billy White Wolf (Sheikh Adnan Alkaissy) took care of that. “He couldn’t teach how to work the ring, but let me tell you―he was a conditioner. He’d make me run the inside of the auditorium in a circle two times, run up and down each aisle, across, come around, and run inside two more times. I was gasping for oxygen. It was horrible,” Higuchi said. “But everything was a learning experience.”

The sweat paid off when the big Hawaiian started in the Pacific Northwest in 1962 for Portland, Ore., promoter Don Owen. Using power moves like bearhugs and full nelsons, he also enjoyed success across the border in British Columbia as part of Canadian heavyweight tag championship teams with Earl Maynard, Steve Bolus and Steven Little Bear from 1969 to 1972.

Higuchi achieved his greatest renown in the Northeast, where promoter Vincent J. McMahon brought him in as Dean Ho after a successful tryout match in October 1973.

“The old man [McMahon] would come out and watch the match. You’d see him watching. He’d just watch a little bit and then he’d walk in back of you to see the crowd reaction. And if it was to his satisfaction, you were in. So I did two shows and he said, ‘I want you out here in five days.’

“I told him, ‘Boss, I cannot make it.’ He said, ‘Sure you can.’ I had to go home to the other coast, fly back, and tell my wife, ‘We’re leaving in the A.M. Morning, morning, morning, as soon as we can crank the engine up.'”

The cross-country trip was apparently mapped out through Murphy’s Law. Anything that could go wrong, did. Among other mishaps, Higuchi lost a muffler and suffered a flat tire on a trailer that hauled his worldly possessions. The expedition took the whole five days. He promptly earned a major win against rival and friend Prof. Toru Tanaka in Madison Square Garden, which represented a little consolation.

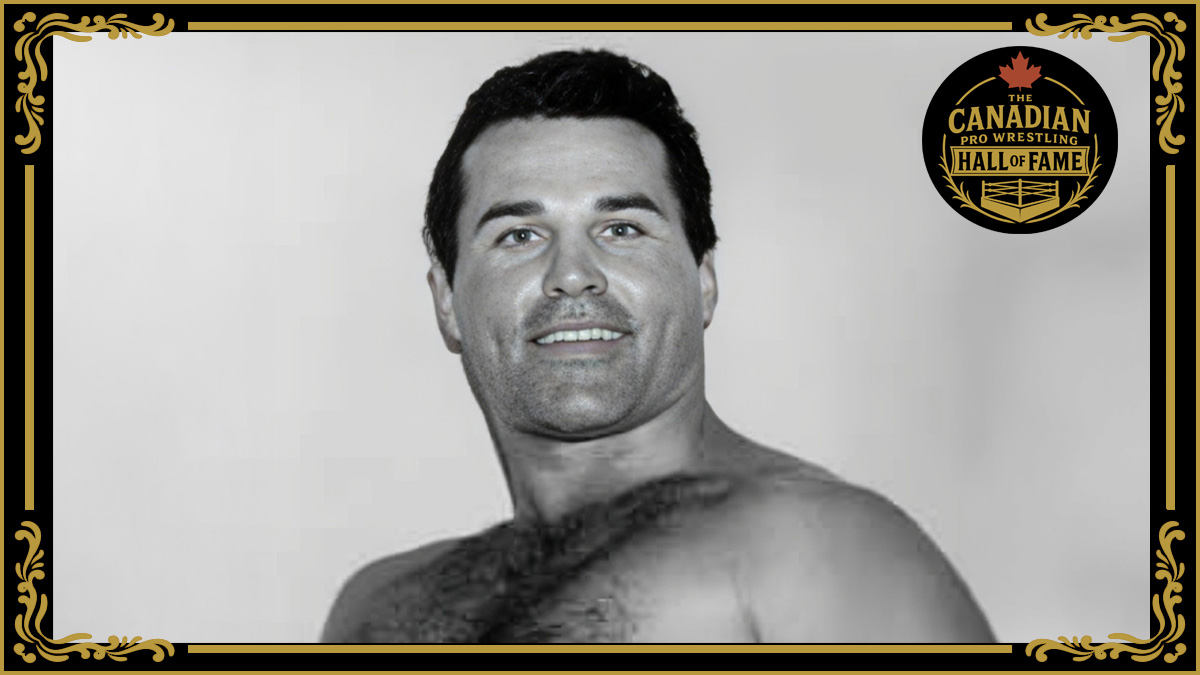

Even more came through the team he formed with New Zealander Tony Garea as a Pacific Rim duo. The partners beat Mr. Fuji and Tanaka for the world tag team titles at a Nov. 14 TV taping in Allentown, Pa., and held the belts until May 1974, when Jimmy and Johnny Valiant defeated them at another TV taping.

Colleagues regarded Higuchi as quiet and relatively unassuming, but that belied his quick wit. Asked in 1973 by a real-life Pennsylvania sportswriter about the talkative Captain Lou Albano, who managed the hated Valiants, he quipped: “Here’s a little bit of philosophy — an empty can makes the most noise. That’s what I think of Albano.”

The money was good, the experiences were enriching, and the crowd’s chants of “Ho, Ho, Ho!” always added a measure of inspiration. But travel in the then-WWWF was unbearable, Higuchi recalled, as he pounded highways from Maryland to Maine seemingly every night. So when he left the WWWF at the end of 1975 to venture into other territories, he decided against a repeat performance in the Northeast.

“I said, ‘I don’t think I can do New York anymore.’ I was just beat. I was in a frazzle. I think I lost about 20, maybe 25 pounds. I wasn’t training because I had no time and I was on the road. That was a hell of a run,” he said. “I don’t know if I could make those long trips anymore.”

Higuchi/Ho also wrestled in Georgia with Garea, and stayed in the Peachtree State into 1977, when he headed to the San Francisco territory. There, he twice held the promotion’s version of the U.S. heavyweight championship. About the only territory he missed was the Minneapolis-based American Wrestling Association, and that was a phone fluke.

“The calls came in at the same time, the same day, New York and Minneapolis. I had just committed myself to New York, hung up, and maybe five minutes, it was Muraco. He said, ‘Hey, I’m leaving Minneapolis and I told them about you. When can you come?'” Higuchi said. “I told them him I just made the commitment maybe five minutes before. It was too bad because I would have loved to have come there.”

His feud in California with Alexis Smirnoff (Michel Dubois) is a favorite of the YouTube.com crowd, since it memorializes an angle in which Smirnoff destroyed Ho’s prized family ukulele. Promoter Roy Shire drew a full house at the Cow Palace in San Francisco off the incident, but the joke was on him. Higuchi said he got about $75 to replace his trashed $50 ukulele. “So that was a money maker for me,” he said.

If Higuchi is indebted to Beyer, others are indebted to him. Ricky Steamboat was just starting out in Georgia, when Higuchi showed him how to incorporate martial arts into his repertoire.

“He was very, very instrumental in showing me how to do it, and when to do it and how to do it in the fashion of a work, and stuff like that,” Steamboat said in a 2005 interview with Jimmy Van. “Yeah, if it wasn’t for Dean, I don’t know if I would have ever done it.”

Mike Shaw was breaking into wrestling in the early 1980s, when he hooked up with Higuchi. “We used to do six towns in Washington and he liked to make those trips with us. He treated me real well and taught me a lot about the business,” Shaw said. And CAC regular Ed Moretti also credits Higuchi with helping his career.

Higuchi phased out of wrestling in 1980s, and has kept a relatively low profile since, though he has attended some of Dean Silverstone’s get-togethers for Northwest wrestling veterans.

For a while, he did some work with a deli operated by Rose, his wife of nearly 40 years. Now she works with the provincial lottery and Higuchi spends every morning save Sundays on a two-and-a-half mile walk with the family’s Jack Russell terrier.

“That’s just about it. I want to keep moving,” he said. “Wrestling is a young man’s business. For me, it had to stop. I had to plant roots.”