While many former professional wrestlers followed challenging careers when they left the ring for the last time, the path taken by John Paul Henning ranks as one of the more interesting and intriguing choices among mat men.

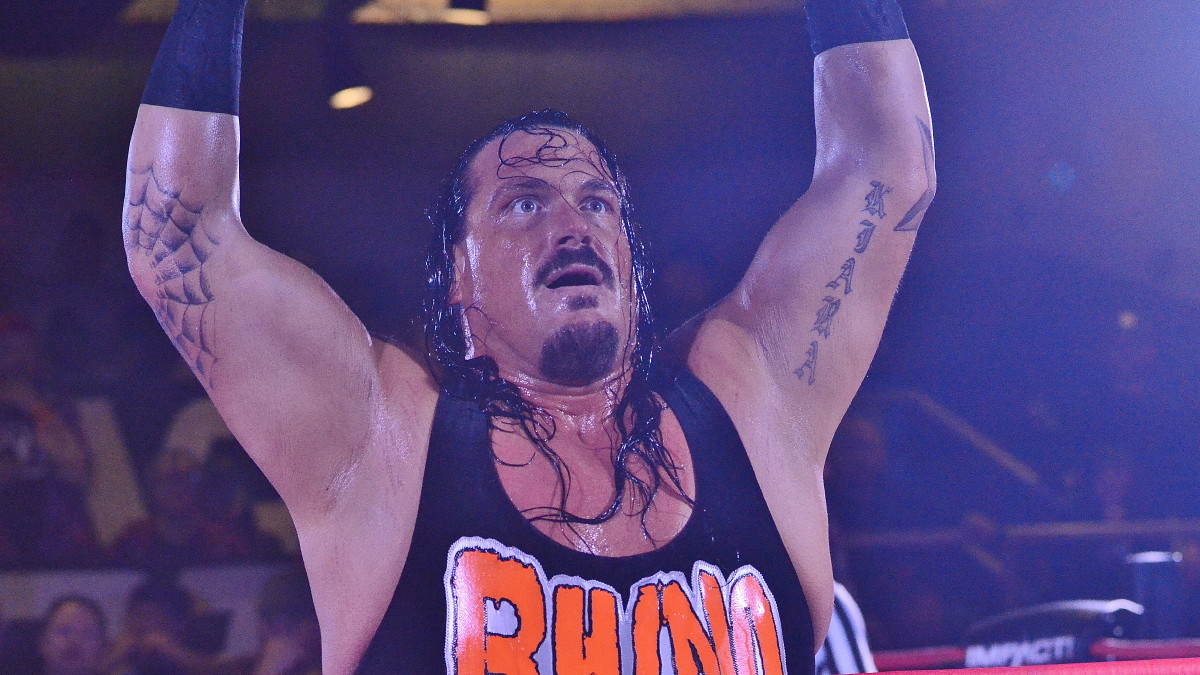

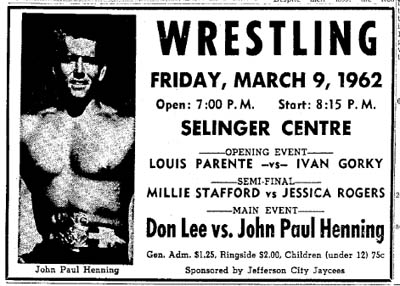

John Paul Henning. Reproduced from the original held by the Department of Special Collections of the University Libraries of Notre Dame.

Henning was a pro wrestler throughout the 1950s and 1960s before hanging up his trunks and embarking on a career as an Evangelist.

While there is much symbolism in Biblical references to water, it was perhaps pre-ordained that Henning would ascend to the pulpit. For it was said that as a former United States Navy frogman during World War II, no man of the ring was more at home in water than Henning.

Even the name John Paul conjures up memories of Revolutionary war hero John Paul Jones who had a remarkable naval career. Indeed it was a most circuitous route the former wrestler-frogman took from pounding the mat to preaching in the evangelical realm.

Henning was born in the Cayman Islands, a part of the British West Indies. His father was a merchant marine who moved to St. Petersburg, Florida where John Paul became a naturalized citizen of the United States at age 15. Like many of the kids from the Islands, Henning spent a great deal of time in the water. When he was 16, he went to sea for the first time as a crew member of a sailboat harvesting large green turtles that weighed 300 to 400 pounds. The food made excellent, though expensive steaks in Florida restaurants.

In high school in St. Pete’s, Henning was a standout distance swimmer as well as a varsity high jumper and sprinter. When he enlisted in the Navy in 1944 it was only natural that after going through boot camp at Bainbridge, Maryland, he put his aquatic skills to good use as he was transferred to the amphibious forces to undertake demolition work.

In an exclusive interview with Wrestling World magazine in 1963, Henning was reluctant to talk about his experiences as an underwater specialist, but was persuaded to give some insight into his activities. It came to light that he was involved in some pre-invasion activity on Okinawa in March, 1945.

“A small group of us frogmen were sent in a few nights before the invasion to make sure there was a clear channel for the landing craft,” Henning told the interviewer at the time. “If we found any coral that might tear up the boats we were supposed to dynamite it. The problem was, of course that there were thousands of Japanese troops on Okinawa. They might not hear us sneak in with our rubber boats but they sure as heck were going to hear when we started blowing things up.”

John Paul Henning. Reproduced from the original held by the Department of Special Collections of the University Libraries of Notre Dame.

Even though the Navy made exit plans for the operation, by having the frogmen picked up and hustled back to the destroyers, not all plans in clandestine operations proceed as mapped out. As a result, Henning and a couple of other men were delayed in reaching the pick-up spot. Only after some heart-stopping moments, were the stranded frogmen able to signal one last boat with a flashlight, as the Japanese began combing the beach area for the invaders.

All ended well as a massive force of Army and Marine divisions rode their landing craft into the harbours cleared by the frogmen and the last bloody battle of World War II was under way.

When the war ended, Henning didn’t have enough service to rate an immediate discharge so he returned to the naval base at Jacksonville, Florida. It was there that he got on the base wrestling team to help make time pass. He met a few service men who were professionals and realized he could hold his own against them.

After the war, he went to work in the real estate business for his father in St. Petersburg but the life became too tame for young John Paul so he became a pro wrestler in 1950. Thus, Henning’s second career began in earnest under the guidance of veteran Pat O’Hara. He was also trained by Bill Longson and Bobby Bruns. Henning and Bruns held the NWA Hawaii Tag Team Championship in 1954.

As a much sought after babyface, Henning had a distinguished career and toured the world. One junket took him to South Africa plus almost three months in Europe and the Middle East as well as a few matches in the South Pacific area. In 1956 he teamed with Lu Kim in Phoenix, Arizona to beat Art Nelson and Rip Nelson for the Western States Tag Team Titles (Arizona, Colorado and Utah). Later in the year, he and Paul DeGalles held the belts.

That same year at the world famous Calgary Stampede, Henning was beaten in a title match by NWA World Heavyweight Champion, Whipper Billy Watson. When he returned to Calgary in 1959 to work in Stampede Wrestling, he and Ed Francis held the International Tag Team title, winning over the mad Russians, Ivan and Karol Kalmikoff. They eventually lost the belts to Johnny Valentine and Chet Wallick.

So busy was Henning that he only found time to return to his Florida home several times a year where he had a 22-foot schooner called The Seafish. He never lost his love for the water and even on the road he frequented YMCAs at every opportunity for a daily swim, in an effort to work out the kinks in his road weary body.

He believed in physical fitness and throughout his career, carried a muscular 240 pounds on a 6-foot-3 frame.

“Your body doesn’t get old from use,” he often maintained, “it’s from lack of use.”

His most effective submission hold was the “bow and arrow” which he developed himself. It consisted of Henning grabbing his opponent’s chin and leg and placing both his feet in the middle of the man’s back while pulling at the same time. Henning thus became the arrow and his opponent the bow.

In the early 1960s he was at the top of his game, meeting all the big names in the business. He partnered with Sonny Myers in a tournament in Kansas City, Kansas losing the final match to Tony Gonzales and Donald Lortie who wore hoods as the Medics.

Henning’s greatest success and most memorable matches seem to have occurred for Sam Muchnick in St. Louis where he became an early favourite. Author Larry Matysik recalled a 1961 tilt between Henning and Buddy Rogers at the Kiel Auditorium before 12,482 fans that had a muddled ending. Just as it seemed Henning had Rogers at his mercy with the bow and arrow, the bell sounded and the house lights went on. Seems the referee had been knocked out in a collision with Henning. Another referee had rushed to his fallen comrade’s assistance but neither official had terminated the match. Therefore the combatants were ordered to resume the affair and soon Rogers pinned Henning for the win. A week later, Muchnick voided the win and ordered Rogers to give Henning a rematch.

Since there was much “heat” in the building over the ending of the match, it gave the industrious Muchnick ample time to milk the grudge match in the newspapers, television and in the “Wrestling” news. A large crowd that was fully informed of what had transpired, return to the Kiel several weeks later to witness Rogers get a clean pin over Henning.

“The fans accepted the decision,” recalls Matysik. “Henning was a star and Rogers was on his way to the NWA title. Such scenarios later became known as the ‘Dusty finish’ wherein the good guy would get the fall only to have it taken away because the referee didn’t see it.”

Henning and Rogers would meet again when the Nature Boy became NWA champion. In one match, victory was within Henning’s grasp but he suffered a match ending injury and had to settle for a draw.

In the summer and fall of 1963, John Paul was particularly active in Toronto. He teamed with another seafaring old salt named Sailor Art Thomas to beat the team of Johnny Valentine and Bulldog Brower for the International Tag Team belts in July. A month later they dropped the straps to Valentine and The Beast (John Yachetti) before reclaiming them in the fall. They also defended the title against Professor Hiro and Fred Atkins.

In June of that year, Henning supposedly beat Valentine for the NWA United States Heavyweight Championship in Washington. However in July in Toronto, Valentine recaptured the title beating John Paul.

Henning had a healthy respect for old nemeses such as Rogers and Valentine. But he was also impressed with Lou Thesz and Pat O’Connor for their scientific style and know-how. When meeting Thesz, he always waited for Lou to make the first mistake but at the same time watched carefully that he didn’t become ensnared in Thesz’ grapevine hold. He was impressed with O’Connor’s “savvy, size and speed.”

But Henning was also wary of the strength of his opponents and admired Yukon Eric for his ability to break out of holds.

“A fellow like Yukon Eric is able to make up for much of what he lacks in wrestling ability because he is so powerful. He breaks out of holds just on his muscle. A very dangerous opponent,” was his assessment of Eric at the time.

Henning also added Cowboy Bob Ellis to his list of fearsome foes: “Ellis goes for that bulldogging headlock and he can put you in pretty bad shape with it. After he drives your head into the mat four or five times with all his might behind it, you’re in no shape to fight back. Then he pins you.”

It was obvious that Henning never picked his spots when you realize that Dick the Bruiser, Rip Hawk, Killer Kowalski and Gene Kiniski appear on the list of opponents the wrestling frogman faced in his career. At the end of 1967, when Sports Review Wrestling rated the top grapplers in the NWA, Henning was listed sixth, behind World Champion Gene Kiniski, Fritz von Erich, Eddie Graham, The Sheik and Valentine.

While John Paul soared with the eagles in the wrestling world, it was evident that he had loftier ambitions in life. His evangelization came that same year when he purged himself of mayhem on the mat for a more fulfilling life in religion. His epiphany came a year earlier after an automobile crash near Denton, Texas just three days before Easter in 1966.

“I was on the critical list and many doctors didn’t give me a chance to live. But many people prayed for me and I became well,” Henning told the Alton (Illinois) Evening Telegraph in a 1967 interview. “While I was recovering, the Lord called upon me and I felt his powers, and I knew I must do his work because he healed me.”

Henning’s aspirations for the future were ambitious. After wrestling he and his wife Peggy operated Slenderline Executive Health Club in Alton. Their 13-year-old son Jim was in high school at the time.

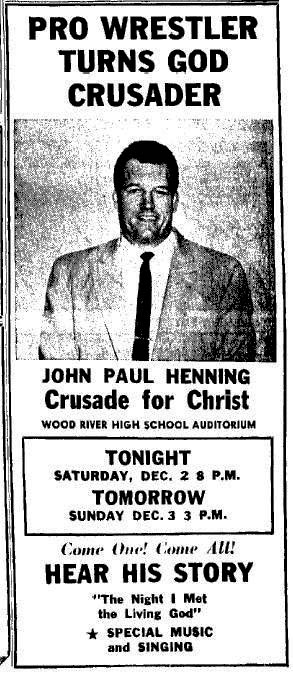

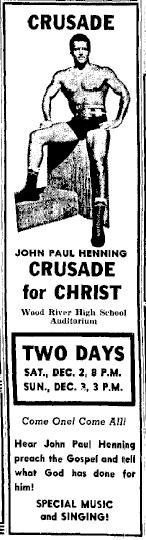

“I hope someday to be as great as the Reverend Billy Graham,” he told the interviewer, as he announced plans for his first “Crusade for Christ” which was held in neighbouring Wood River, Missouri.

Jefferson City, Mo., clipping.

As he carried out crusades over the years, there is no evidence that he ever attained the worldly status of the Reverend Graham. But he did share the stage with music icon Pat Boone in 1972 when the pair appeared at a church fundraiser in Benton, Missouri.

By all accounts, John Paul Henning was not the easiest subject to interview because of his modesty and quiet nature. Perhaps his reticence contributed to so little being known about his ministry or life after wrestling.

Comments from Cowboy Bob Ellis appear indicative of many who worked with him.

“I remember him very well,” recalled Ellis. “I didn’t run around much with him. But he was a good worker. He could get ‘em up. He didn’t try to take too much. We got along good in the ring. There was no animosity or anything. I didn’t know too much about him. I didn’t know that he became a preacher.”

Henning died on July 1, 2001 at the age of 73. He may not have attained Billy Graham’s evangelical standing but neither is there any indication he ever became mired in controversy as often befalls those who preach the word of God.

But whether he was in the water or on the mat or in a house of God, all indications are that he was a man of great conviction who pursued his ambitions to the fullest extent.

— with files from Greg Oliver