He wasn’t under the klieg lights at the Omni in Atlanta. No one was chucking rotten tomatoes at him. Instead, Gary Hart’s last wrestling gig found him outside a storefront in Allentown, Pa., woolen hat pulled low over his bald head, sharing the good times and the bad between drags on a Marlboro cigarette as he prepared to catch a plane home to Texas.

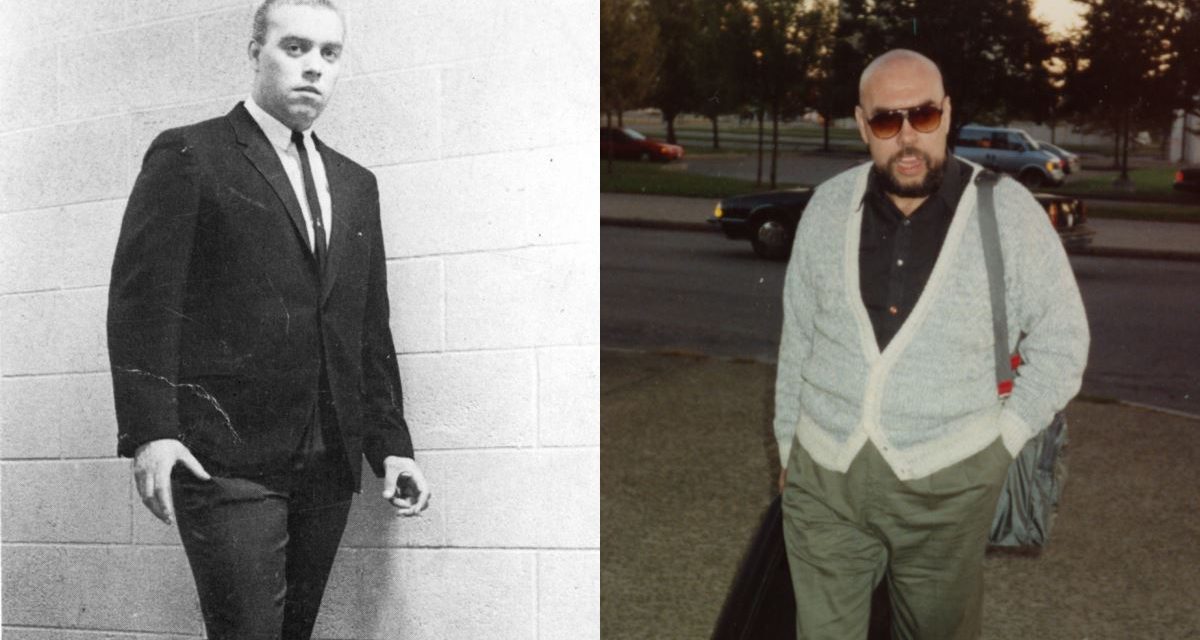

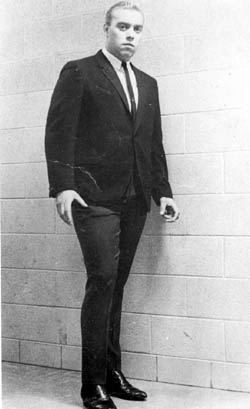

A young Gary Hart.

A fan brought up Hart’s brief stint as manager of unpolished giant Jeep Swenson. “Oh jeez, don’t remind me,” he quipped. “That was awful.” Another recalled how Hart’s friend Don “The Spoiler” Jardine could walk on the ring ropes. “And those were the old-style ropes,” Hart was quick to add. “They didn’t have the heavy cables in them. It was much more difficult to do.”

Then, having signed autographs and mingled with old-school fans for a few hours, Hart shook hands, thanked everyone for coming, and hopped in a car with fellow Texas hands Skandor Akbar and Bill Irwin on Saturday for his final trip home.

Hart’s unexpected death Sunday at 66 was a thunderclap across the wrestling world. Many fans first encountered him as a nefarious manager of wrestlers like Jardine, the Great Kabuki, Bobby Duncum and Pak Song Nam. Others vaguely recall he survived the February 1975 plane crash near Tampa, Fla., that claimed the life of Bobby Shane. A few old-timers might know that he managed an up-and-comer named The Student in Michigan in the early 1960s — the future George “The Animal” Steele. And Hart was an infamous tormentor of the beloved Von Erich family in the Texas-based World Class Championship Wrestling during the 1980s.

But what few fans realized is that Hart, born Gary Richard Williams, grew from a kid on the streets of Chicago to become one of the most creative behind-the-scenes minds in the history of wrestling. But he wasn’t one to brag. Friends said that represented a bit of modesty from someone whose on-camera persona as a first-rate heel was just that — an on-camera persona.

“He felt very comfortable talking about other guys. He wasn’t comfortable talking about himself,” said Philip Varriale, who collaborated with Hart for almost three years on his nearly finished autobiography and described him as one of his heroes. The book — a working title is My Life in Wrestling: With a Little Help from My Friends — is being copyedited and will be published later this year, Varriale said.

“If you tell someone you’re writing a book with Gary Hart, they’ll say, ‘Oh, that’s the manager from World Class.’ But to me, I could just go on and on about the places he went and the things he did.”

James Beard, a longtime referee and front office staffer in Texas and elsewhere, praised his old friend as someone whose word was his bond, even in the deceptive world of pro wrestling.

“The thing about Gary Hart is from the first time I ever worked with him or ever knew him, I can honestly say never misled me about anything. That’s one of the things about Gary,” Beard said. ” A lot of deaths hit you hard, but guys like Gary who you were really close to, that’s tough.”

As a booker, matchmaker and television producer across the country, Hart said he went out of his way to avoid shoving a wrester down fan’s throats, and in so doing, was responsible for creating some of the sport’s most memorable moments.

“I always looked at myself as a matchmaker. I found talent the people were interested in,” he said. “My theory was if the people recognize you at the top of the ramp, you have a chance. And the further you go down the ramp before they recognize you, the less chance you have. My idea was if the people like them, then I can present them in a way to make them draw money.”

Williams got hooked on wrestling as a child and started under the tutelage of Billy Goelz, a top light-heavyweight in the Midwest. Goelz got him a job at the Marigold Arena in Chicago and Hart, a competitive swimmer in his youth, debuted at 18 in May 1960 against Sailor White in Beloit, Wis. He picked up the new surname from a man who saved the life of his uncle during the Korean War, a favor that he honored with a heart tattoo on his arm.

Early on, he dabbled in some managerial duties for Angelo Poffo, patterning him as a playboy version of Bobby Davis, manager of Buddy Rogers, one of wrestling’s biggest stars in the 1950s and 1960s. Managing The Student in Detroit, he incessantly defended his charge’s lack of scientific wrestling, saying he was, after all a “student.”

During his swing through Allentown he recalled that led to a match against announcer Alan Ruby, son of Detroit promoter Bert Ruby. “And now Alan Ruby is a big-time lawyer and he’s defending Barry Bonds,” Hart chortled. “So who’s defending whom?”

Hart always had a knack for creative finishes and ideas, learning at the hand of Jim Barnett, whom he called “probably the greatest promoter I ever worked for.” One of his best came in Texas in the mid-1960s when he came across Jardine in Amarillo. Jardine was a rangy, athletic sort who’d been in the business for about a decade. “Here was a guy who was too good-looking to be a heel,” Hart recalled. He put him under a mask as The Spoiler and the two rocketed to the top of the charts across the country.

Hart was the driving force behind a pair of Japanese sensations, the Great Kabuki and the Great Muta. For years, Hart conceived the notion of a grappler who could mix martial arts with traditional Japanese theater. With the help of Bruiser Brody, he found the right fit in 1981 with an undersized wrestler named Akihisa Takachiho, who spewed green mist (actually a food coloring mix). So confident was Hart that he dipped into his own wallet for the gimmick — the Kabuki wig cost more than $5,000 and the wooden masks cost $250 each.

“When we walked into the dressing room, we had all these wrestlers and they looked at me like, ‘Gary, you’ve been smoking too much weed, guy. There’s not a chance this guy is going to draw a dime,’ ” Hart said. “I took him to the ring and he was fabulous, he was made the first night and everyone wanted the Kabuki and they quit laughing.”

For World Championship Wrestling in 1989, Hart invented the Great Muta, the alleged son of Kabuki, who also spit out a green mist, but was more oriented toward fast-paced action. Muta was an instant hit, so much so that Hart said that Steele, then a WWF road agent, approached him about the possibility of jumping to New York. But Muta’s visa was sponsored by Turner Sports, the WCW owner, and a move to the Northeast probably would have required a pay cut.

Even few in the business know that Hart was booker in charge of the first Starrcade in Greensboro, N.C., in 1983. That card featured a Kabuki-Jimmy Valiant match, which Hart loved to run and a main event in which Ric Flair won the National Wrestling Alliance world title from Harley Race. Hart said he made $10,000 that night and still looks at it as a milestone in wrestling annals. “The success of the first Starrcade made everyone take notice. That was one of the big factors in developing the pay-per-view industry [for wrestling],” he said.

And no one had a bigger role in the rise of World Class Championship Wrestling in the 1980s, as Hart paired off the Freebirds and the Von Erichs in a classic rivalry as booker for one of the nation’s hottest territories. He booked on and off in Texas for nearly 15 years and lest you think he was all business, all the time, Hart had a clever sense of humor. Bronko Lubich, a minor partner in the Dallas booking office, was known as a referee with one of the slowest counts in the wrestling world, and Hart was glad to rib him a bit.

“Bronko hated to get and count and sometime I would instruct the guys, ‘I want like 15 false finishes real quick. And Bronko would be getting up and down and up and down and he’d tell the wrestlers, ‘Take a fall by the ropes so I can get up.’ ”

Working with Hart was totally different than working with most managers, said Beard, who described it as a chess game.

“He was so intelligent in the way he approached things. He didn’t just insult his opponents — a lot of times, he would praise them and talk about their strengths. Then he’d turn around and say, ‘But I’m going to find a way to beat him.’ And he would do that,” Beard said.

“He just came across as someone you might not have liked, and maybe you hated him, but you had to believe him. I just wish people from this generation could see a guy like him work for 10 minutes because then they’d understand how we got so caught up in this business.”

By 1990, Hart had his fill of politics at Turner and WCW and essentially walked away from the spotlight, though he occasionally dabbled in some local promotions. In recent years, he was a regular at fanfests and Cauliflower Alley Club reunions and participated in the creation of DVDs about the World Class years. He was especially fond of sharing time with sons Jason and Chad at his home in the Dallas area.

Hart had been in good spirits on the trip from Pennsylvania to Dallas Saturday and friends were unaware of any problem with his health. According to several accounts, Jason found him dead on Sunday night after having visited with him earlier in the day.

“That’s what Gary lived for, to take care of his sons. They had such a great relationship,” Varriale said. “He was one of those guys who was so eloquent, so kind, so thoughtful and so compassionate and I really appreciated talking to him. I’m just in shock that he’s gone.”

TOP PHOTOS: Left, Gary Hart in 1960; right, Gary Hart in 1989 by Terry Dart.

RELATED LINKS

- Oct. 27, 2009: Posthumous Gary Hart autobiography one of the best ever

- Oct. 21, 2009: Help from friends and family got Gary Hart’s book to market

- Oct. 28, 2008: Gary Hart Guest Booker DVD a bittersweet masterpiece

- Mar. 17. 2008: Gary Hart: ‘With a little help from my friends’

- Mar. 17, 2008: Manager/booker Gary Hart dies

- May 1, 2001: ‘Playboy’ Gary Hart not so hated