At just 5-foot-9, Mando Guerrero just didn’t have the height to be a main event wrestler in the 1970s and early 1980s. Fortunately, he found a place still in the public eye where his size was just right, though chances are you didn’t notice him.

You see, since 1977, Guerrero has been working as a Hollywood stuntman.

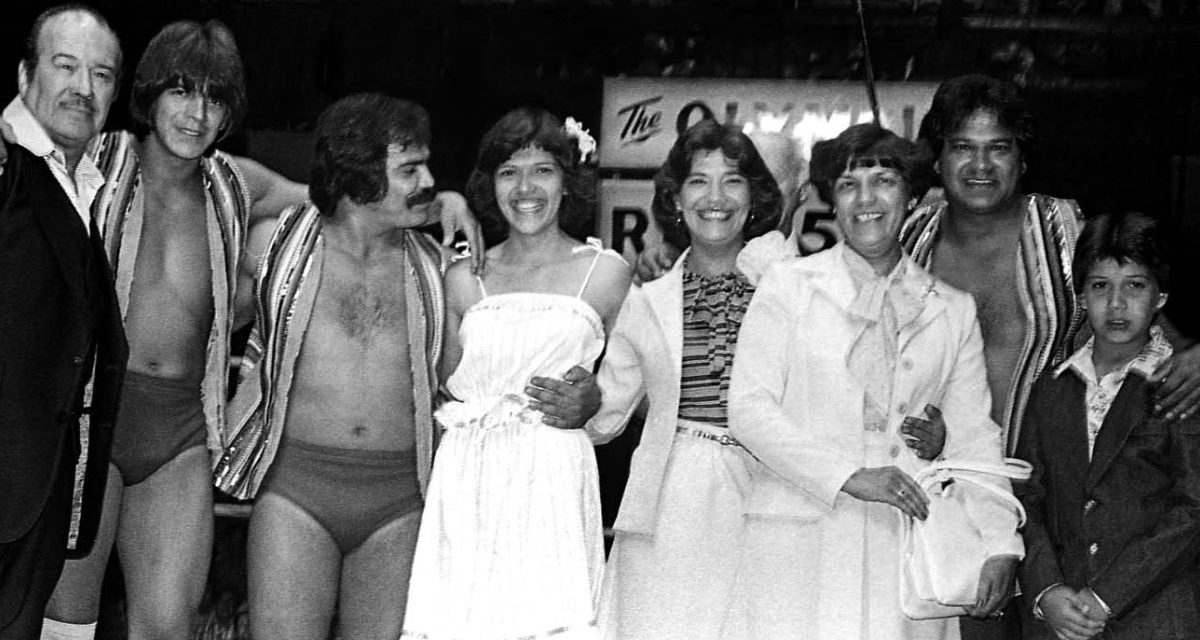

Louie Spicolli, Chavito Guerrero and Mando Guerrero pose at the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles. Photo by Mike Lano, wrealano@aol.com

Like many wrestlers who switched from the grunt and groan game to the acting game, Guerrero owes a debt of gratitude to the “Godfather of Grappling” Gene LeBell.

Guerrero was working for the Los Angeles wrestling office run by Mike LeBell (Gene’s brother). He was a diminutive 165 pounds and was doing his best to bulk up.

“I would go every Wednesday, which was TV day, and I would work out early in the morning,” Guerrero told SLAM! Wrestling. “My thing was to gain weight. In those days, we didn’t know how to gain weight, the science of it today. It was just eat a lot and workout a lot. That was the main thing. Steroid taking wasn’t a must. It was available, but it was just by special guys who knew what they were doing, maybe weightlifters, not wrestlers.”

“Judo” Gene was often called upon as a referee for the promotion, when his own movie schedule permitted. Gene LeBell saw Guerrero’s dedication and agility and spoke up. “He said, ‘You will make a lot of money in Hollywood because of your size. You can be doubling women, you can be doubling children, stuff like that.'”

LeBell said he didn’t have to work hard to convince Mando to make the switch to movies. Mando had already put in time working as a surveyor on a construction site, as a salesman at a Cash Way Store a Rayburn Men’s Wear store.

“Well you know, they weren’t making that much money unless you were traveling around, and it’s living out of a suitcase. Mando was more interested in making a living,” said LeBell. “I was doing stunt work and the guy is a tremendous athlete and tumbler, so I pushed him into doing stunts. I got Chavo, his oldest brother, his first job (on The One and Only), but he never continued with it. You can’t be a wrestler all your life but you can do stunts for much longer. (With stunt work) you have insurance and a pension, but in wrestling if you get hurt nobody gives a darn. I’ve known so many great wrestlers who get too old to do the sport, and they have no money and they’ve got injuries.”

The second son of Gory Guerrero, it seemed destined that Mando Guerrero would follow in the footsteps of his father and his older brother, Chavo Sr., and lead the way for his younger brothers Hector and Eddie, who would surpass them all in fame as world champion in WWE. But Mando had given some thought to acting. “I had gone to the University of Texas El Paso, taking drama lessons there,” he said. “I’d never thought about it seriously, but it was in the back of my mind.” (Besides the two years at El Paso studying dramatic arts, he has also attended Rancho Santiago College and Orange Coast College for TV production classes.)

As kids, they frequented the matches. “We lived for that last match, people are leaving and we jumped the ring. We just started carbon copying everything we’d seen. We lived for that,” Mando explained. “Every second-generation wrestler that I met would live for that time, even though there were other children in the arena jumping into the ring, we ruled — and we knew it. We used to do the same thing in Mexico.”

The training that came in Texas and Mexico lead to the unique Guerrero skill set. “We came out with this dual style that we knew how to adapt real easy. So my father, with his traveling, actually educated four wrestlers that were naturals to the sport. I don’t want to talk like that, but it’s the truth, man.”

Mando Guerrero throws a punch in Tijuana. Photo by Mike Lano, wrealano@aol.com

Mando never saw his in-ring persona as anything but real life. “I was a Mexican coming in from Mexico, I was a second-generation wrestler, I was short — that was nothing but ammunition for the heel to grab and to use to dig at the people, because that’s how the people identified themselves with me,” he said. “There was no such thing as a fantasy, made-up character. In those days, you used your real-life persona, I should say most of us would use our real-life persona.”

Most of the success in his career came in Mexico or while based out of Los Angeles, where he was a mainstay for years, often teaming with his brothers Chavo or Hector. He also formed championship tag teams with Tom Jones, Carlos Mata and Al Madril.

But he found there to be a glass ceiling, a level of stardom that he just wasn’t going to hit. So when Mike LeBell — Gene’s brother — asked him to meet with a producer who was interested in making a movie about wrestling, Mando was right there.

It was 1977, and there was a Screen Actors Guild strike going on. Mike LeBell instructed Mando to get rid of the producer. “I don’t want him around. All they do is call us fakers. I don’t want be involved. Whatever you do, just get rid of him,” Mando recalled Mike LeBell saying.

“I went into the interview with that attitude. So I started mouthing my mouth off, cussing him off. Finally I said, ‘I’m sick and tired of you guys. You always come over here and say that we’re fakers, that we fixed this, we fixed that. You really don’t know until you start traveling with us, and really catch the essence of what this business is all about,'” Mando told the producer, who agreed, and asked to travel with the wrestlers.

When Gene LeBell found out that Mando had developed a relationship with a Hollywood producer, instead of reacting like his protectionist brother, he told Mando to ask for a SAG card so he could start working. Then Gene offered up the advice that Mando fortunately adhered to: “Whatever you do, pay the dues. Whenever you get tired of carrying it, and it’s burning in your pocket, you call me and I’ll tell you what to do.”

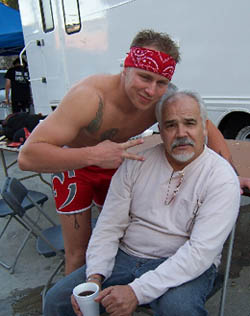

Altar Boy Luke and Mando Guerrero on the set of the WSX pilot taping last March in Los Angeles. Photo by Mike Lano, wrealano@aol.com

Mando struggled on the wrestling circuit a while longer, then decided he wanted to get into acting. Gene LeBell told him to be an extra for three years.

“Gene came to the set one day, and he saw me sitting at the back with all the extras. He walks up to me and he says, ‘What are you doing here?’ I said, ‘This is where they told us to sit.’ He said, ‘That’s not how you’re going to learn. You see that camera? Where that camera goes you go. Stay out of the way, keep your mouth shut, keep your eyes and ears open and learn. After three years, come and talk to me again,'” Mando recalled.

After three years, Mando had a good resume and knew how to do some stunts, and knew some of the stuntmen. This time, Gene told him to start visiting the sets. “Little by little, I started getting calls, to do this, to do this fall, to do that fall. I learned how to do crawl work, I learned how to rappel. Now I know how to box. You start learning as you go along. I learned how to do high falls, jump around on a swing, all that, how to act in movies, how to do a movie punch, how to sell.”

Gene LeBell explained the dedication needed for stunt work. “There’s no instant success, and stunt work’s a little different because you have to be your own agent,” he said. “The shots are called by other stuntmen, so you get hired by people you know. He’s a good actor, but it’s a tough business to break and he’s a great stuntman.”

Mando Guerrero’s acting headshot

But Mando wasn’t ready to give up the wrestling.

“I always divided myself between wrestling and this. I became what they called a no-show. I would work three, four months a year in L.A., and wrestling in the local areas … then I would do stunt work like that. Then I would get myself booked, like say in Oregon, and I would go wrestling in Oregon for eight months,” he said. “So obviously I wasn’t doing nothing here in the movies. So I would come back down to L.A. and I’d start doing the rounds again, pick up my reputation.”

Finally, Gene LeBell stepped in and told Mando’s wife to keep him from wrestling. “He’s never going to get settled here in this business unless he stays here and works it,” LeBell told Mando’s wife.

Gene put things in perspective for Mando, and made him realize that he wasn’t going to be a main eventer, so he should give up the wrestling. “I will always be indebted to Gene for that, for opening my eyes.”

The goal of a Hollywood stuntman is generally to not be noticed, filling in for the big star during a dangerous scene. Feel free to look for Mando in some of these films: Miracles (1986); Red Surf (1990); Eve of Destruction (1991); Falling Down (1993); Steal Big Steal Little (1995); My Giant (1998); Critical Mass (2000); Picking Up the Pieces (2000); Submerged (2000); The Shrink Is In (2001)

Mando found some similarity between his passion for wrestling and stunt work. “You cannot do a stunt halfway. You’ve got to shoot for it all the way, the best way you can do it in order to keep it safe, keep yourself from injury,” he said. Hence, he also gets many to work as as a stunt co-ordinator and choreographer for wrestling scenes in movies.

Mando, Chavo Jr. and Eddie Guerrero. Photo by Mike Lano, wrealano@aol.com

Even now, at 57 years of age, Mando still feels the call of wrestling. He’s seen his brother Eddie come and go, his nephew Chavo Jr. carry on the family name and, for a time, bring in Chavo Sr. (Classic!) as a manager.

Just like they did years before, the Guerrero brothers still get called into action on occasion. As recently as July, Chavo, Mando & Hector teamed to defeated Villano IV, Rey Misterio & Haku.

He truly loves the sport, and follows today’s WWE with a keen eye.

“It’s the evolving of the sport. Now you have Hollywood coming in and governing the portrayal of the business. Regardless of what happens to get those two performers in the ring, it’s still those two performers who should have enough knowledge, enough respect, to put on a show that’s worthwhile. That takes a lot of skill,” he explained, going on to praise his late brother, Eddie, who died in November 2005. “It’s not that I’m a Guerrero or whatever, but sit down and compare to the matches my brother Eddie had. See the damage of the other wrestler. Eddie, there were very few wrestlers who ever got hurt with Eddie wrestling them. Eddie got hurt by many of them because they didn’t know how to execute good. It’s all the illusion.”

Mando has even gone as far as applying for a job as a WWE road agent, hoping to share his knowledge and passion with future generations.

“I’m not saying that it’s all bad, but I am seeing a lot of mistakes. I am a technician. I think it should be every detail, every step, every punch, everything’s got to be down to a ‘T,'” he said.

On a roll, he continued: “Every wrestler now comes into the game thinking wrestling is fake, that is why their performance is weak. Having the opportunity to work both in the pro wrestling world and the Hollywood scene, I would like to tell all new wrestlers how important it is not to cheat the ticket-paying audience. By applying the moves and holds to their full strength and striking and completing every punch with the correct timing, the chemistry between them and the wrestling fan would be real magic.

“Eddie and I would sit and dissect his matches down to every detail, such things as, would a move have better force by place his feet in a different position? Most performers are too involved in their ring persona rather than their ring performance. The connection between me and the audience is the passion of the detailed delivery of my performance. My brothers and I were taught to give the fans the truth. Eddie had a whole family that supported him. People still chant his name.”

— with files from Dave Hillhouse

Greg Oliver, and his co-author, Steve Johnson, got some flak for not including Los Guerreros in their book, The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Tag Teams. Well, both Chavo Sr. and Mando contribute their thoughts on opponents like John Tolos, Bull Ramos and Roddy Piper to the upcoming The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Heels (Spring 2007), and the Guerreros are slated for The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Heroes somewhere down the road. It just goes to show that it pays to complain.