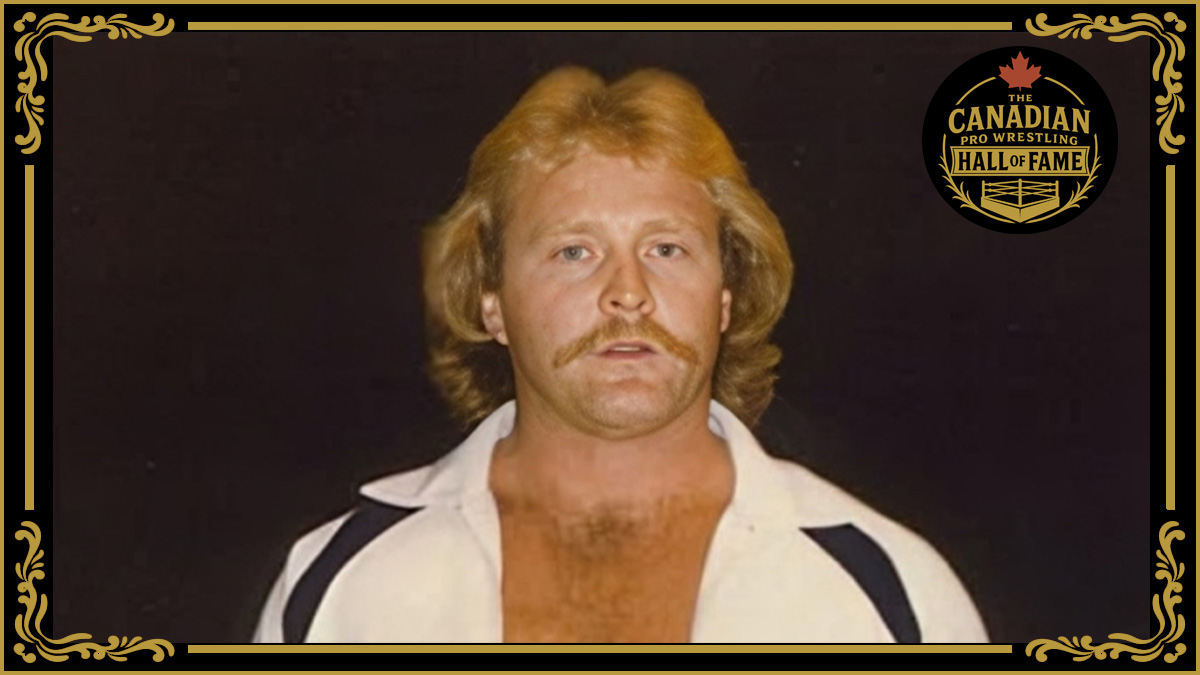

REAL NAME: Barnabus David Kochen Lane

BORN: January 7, 1956 in White Rock, British Columbia

5’10”, 226-230 pounds

In basketball, they talk about blue chip prospects, in hockey, the top juniors get the scouts all excited. Imagine taking the same premise to pro wrestling, and you’re looking in at the class of 1972, training with Verne Gagne. There are Olympians Kosrow Vasiri (The Iron Sheik), Ken Patera and Chris Taylor, a couple of promising youngsters in Ric Flair, Buddy Rose, Rick Steamboat, and Buddy Wolfe.

But this story isn’t about them, it’s about the unheralded, late-round draft pick, Barnabus David Kochen Lane, who despite following his father’s footsteps into the mat game, got next to no publicity early in his career. Yet almost 30 years later, it’s ‘Buddy’ Lane who is one of the key people behind the scenes in the Maritime promotion Real Action Wrestling, grooming some of the potential stars of tomorrow.

Lane is a traditionalist through and through, teaching his new charges to stay grounded, learn the ropes properly before trying anything fancy. Sounds a lot like wisdom he picked up from AWA veterans like Gagne, Nick Bockwinkel and Ray Stevens.

Lane’s father was The Big K, ‘Wild’ Bill Kochen, who originally hailed from Sioux City, Iowa, and settled into the AWA way of life, retiring from in-ring action in 1971, and refereeing after that.

Like his dad, Lane was athletically gifted, but was only 5’10”. “Wrestling was just something that I always wanted to do,” Lane explained to SLAM! Wrestling.

His dad got him into the training with Gagne. The camp was the easy part compared to his first few years in the business, setting up rings, being a referee and getting used as a punching bag. “I went to the camp and they kept telling me I wasn’t ready. You go to the camp again and they say you’re not ready yet. Then when I was finally ready, apparently, when you run into guys like Blackjack Lanza, the Super Destroyer, Angelo Mosca, Blackjack Mulligan, and you get pounded night in, night out by these big monsters … you kind of ask yourself, ‘Is this what it’s all about?’ Because when you get to work with a Stevens, a [Pat] Patterson, a Bockwinkel, who were like wrestling technicians, it’s a whole different thing. You get to wrestle with those guys, in and out of holds. When you get into a match with a Stan Hansen, it’s just a slugfest. That’s sort of how you earn your way. You just get pounded and pounded and pounded. If you cry wolf or complain, they just tell you to go on home, kid, you’re not tough enough.”

His hard work paid off, and he eventually carved himself out a spot. “I just kept coming. I remember Angelo Mosca blackened both of my eyes and I broke my nose when I starting out. I never said a word, I kept on going,” he explained. “The thing is, if you want to be a wrestler, whether you’re smaller or not, if you know your craft inside out, you work out, you show the fellows that you’re there to stay, eventually you’re going to pound out a spot for yourself.”

Size was certainly an issue to some people, but Lane downplays it. “I was always under the assumption that if you can take them all down on the mat, they’re all the same size.”

His name Buddy Lane comes from a childhood nickname, and his mother’s maiden name.

Lane’s first territory outside of Minnesota was Gene Kiniski’s Vancouver promotion, where he was sent for seasoning in 1974. He quickly realized that he had actually had it great, starting out in one of the biggest, most important promotions. “All these guys would give their eye teeth to work in Minneapolis,” Lane said. “There was no free ride there. You had to live it, eat it and breathe it.”

Besides Vancouver, which he figures he returned to at least 10 times, Lane hit Kansas City, Portland, Calgary, Winnipeg, Montreal, California, Florida, and did stints in Europe, Japan (with Harley Race), Korea and Jordan.

His favourite stint was the AWA in the mid-’80s. Some of the top talent was there, and he was regularly taking on greats like Nick Bockwinkel and Billy Robinson.

And there was the title chase. “I used to chase Steve Regal around, Mike Graham, Rock’n’ Roller Buck Zumhoff for the lightheavyweight crown,” Lane explained.

Every time he came close, the belt was kept from his permanent grasp, especially against Steve Regal (not to be confused with William Regal of today’s WWF). “It’s all a work anyways, but you beat him for the light-heavyweight crown and then they weigh him, he’s overweight, so the title can’t change hands,” sighed Lane. “I’d chase him all over Minneapolis and around the United States again.”

On one occasion, Lane beat Regal in a non-title match, then Mike Graham beat Regal for the title. Lane’s chase of Graham then began.

Throughout his career, Lane was pretty well always a babyface. “It was better suited for me because I had the wrestling background, but I always sort of wanted to be the heel. Guys like Verne, Gene Kiniski and that said ‘No, no, you’ve got blond hair. You’re too good looking to be a heel.'”

In 1984, he got a chance to head to Eastern Canada. “I was talking to Bob Brown and the Stomper and they were going to the Maritimes. I didn’t really know the Maritimes. They said, ‘You know where Leo Burke is from, right?’ I said, ‘Yeah, New Brunswick’. ‘Well, they call that the Maritimes.’ Well, I’d heard about it. I got to wrestle in the best place there was. So Brown says ‘Gimme some pictures and I’ll take them down there.’ So he took my pictures and took them to [promoter Emile] Dupre. He saw me on television and he called me and asked if I wanted to come in. In the summers in Minneapolis, it does get slow. It was known as a winter territory. So Wally Karbo says ‘Go ahead, go.’ I came down here the summer of ’84 and worked against Archie Gouldie, The Stomper, Bob Brown, Mr. Pogo.”

He was an instant hit because the AWA TV show was seen in the Maritimes. The style of wrestling was different than many of the other territories he worked. To Lane, the fans out East want “rock’em’sock’em wrestling”

“When the Cuban Assassin told me to get a chair, I got the chair and I broke it over his head because if I didn’t break it over his head, it was coming over mine,” Lane said with a laugh.

The East Coast was home before he knew it. “I met my wife and I ended up staying here. Otherwise, I would probably be in Florida or if this place hadn’t have panned out, I would have been living in Portland, Oregon with [Roddy] Piper and Buddy Rose.” With the Maritimes being primarily a summer promotion, Lane has had to find some other jobs to keep him busy. He has run a wrestling school, promoted a bit with Stephen Petitpas, worked as an inventory control manager for a furniture store and is even certified to work on the oil rigs offshore.

In the Maritimes, Lane worked with Emile Dupre for 10 years, helping to book and promote the territory. The promotional aspects had come pretty easy for him, having been around so many territories and promoters. “Hanging around with Wally Karbo and Verne Gagne, watching those guys do it, it’s just common sense. You’re booking towns, you’re booking this, you’re booking that,” Lane said. “I learned from Gene Kiniski, I learned from Wally Karbo, I learned from the Grahams in Florida. You pick up all these little things.”

He admires the job Dupre did. “He did a great job. He ran for 30 years, worked seven days a week, twice on Sundays. You’ve got to give him credit, whether he’s running today or not.”

Being a student of wrestling over the years has paid off for Lane in his latest capacity as booker and teacher for the fledgling Real Action Wrestling promotion in the Maritimes.

“Buddy is an important part of Real Action Wrestling. You can’t replace that kind of experience. Technically, and especially on the mat itself, he is awesome. He has helped some of the younger guys to learn holds and counter holds,” explained Warren Olson, one of the primary investors in Real Action Wrestling. “The other thing about Buddy, he is extremely passionate about this business. He holds it very dear to his heart. When he speaks about it, you know it’s coming from his heart. He doesn’t pull any punches for sure. He has been very helpful in helping us get established from both a worker and advisor’s point of view. He has adapted well to the evolution of this sport becoming more about entertainment, while managing to keep and integrate the things he has picked up in his 20+ years in the ring.”

Lane finds that he is trying to instill different skills in the youngsters wrestling in the promotion. “What we’re trying to do is bring them back the way the wrestling was, learn how to wrestle on the mat, learn how to wrestle to your feet, do your spot, catch the guy with something, take him down to the mat, wrestle your way out of a spot rather than punch and kick your way out of a spot. Then it shows that there is a bit of a competition going on there.

“The ideal is, the reason a heel heels is the babyface outwrestles the heel and then the heel gets so pissed off and frustrated that then he pops the babyface. Then the babyface gets pissed off, and he’s got the fans behind him, and the babyface kicks the sh** out of the heel. Then you all go home, the babyface gets his hand raised and the people are happy.”

He is also trying to teach the psychology that goes behind the wrestling. “Years ago, when a fellow got poked in the eye, the heel conceals it from the referee, then he pokes him in the eye. So then you get the mileage out of why the guy did it. If you do it flagrantly in front of the referee, why’s the referee there? He may as well sit in the front row, just watching the two of you beat the daylights of our each other.”

To Lane, the current WWF scene is suffering because of the lack of wrestling. In the early days of the WWF’s rise to prominence, the stars were wrestlers first. “They put these gimmicks onto these fellows, all these images … it was very easy for those fellows to adapt to a gimmick because they had the wrestling background, they had the style. The fellows that are coming up today, they give them a gimmick first and they don’t how to wrestle. Then they learn the wrestling second and that’s why the product is unbelievable.”

He tries to be as good of a teacher as the ones he had. “I made mistakes along the way, but I had great teachers to correct my mistakes. Ray Stevens became a good friend of mine, Pat Patterson, Nick Bockwinkel, guys like that, they just tell you, ‘Look, this is the way you’ve got to do it.'”

The advice extends beyond the ring as well. Life on the road can be a challenge for a young wrestler. “When I was coming out of high school, that was the greatest thing, to be partying, being on the road in the hotel rooms and all this other stuff. After a while, the years go by, and you’ve spent all this money. You made a hundred grand or more, and you’re sitting there wondering, ‘Where’d all that money go?’ You partied it all away.”

So Lane finds himself showing the youngsters how to save their money as well as how to do a headlock.