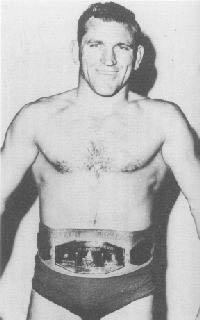

Danny Hodge. |

Danny Hodge sits on his porch in Perry, Oklahoma these days with his wife Dolores, content to take life easy. An accomplished woodcrafter, the 68-year-old Hodge spends his afternoons whittling out wrestling ornaments, trunks, toys and belt racks from a mounting woodpile.

The tranquility of life in Perry contrasts starkly to the world of pro wrestling he dominated as the perennial National Wrestling Alliance World Junior Heavyweight champion from 1960 to 1976. At 5′ 10″ and a mere 220 pounds, you would guess that Hodge hardly intimidated most wrestlers he worked with.

You’d be guessing wrong.

“(I was) smaller than everybody,” Hodge admitted to SLAM! Wrestling over the phone recently. “But God gave me a lot of strength, a lot of stamina, a lot of conditioning. I had knowledge of holds, I could wrestle and I could fight so really I had five strikes against you when you stepped in the ring with me.”

For close to 16 years, Hodge instilled the fear of God into everybody around him. Graced with a wiry, muscular build and lightning-quickness, Hodge was universally considered the toughest wrestler in the industry. As the legend of his toughness grew, one truth became a universal law that all wrestlers understood: You didn’t mess with Hodge.

“When you got in the ring with me, you were going to wrestle, whether you wanted to or not,” laughed Hodge. “When (fans) wash clothes all week and washing and ironing to buy a wrestling ticket, you come to see wrestling. I can guarantee you you’re going to wrestle.”

“Sputnik Monroe… sometimes I’d take him over in a headlock and he’d just lie there. Well, if you don’t try to get out, I’m not going to lay there, I’m going to turn you loose and get up and if you don’t move I’m going to stomp you.”

An accomplished amateur wrestler, Hodge first gained national recognition wrestling on the Perry High School team by going undefeated his entire time there, helping to turn the school into a wrestling giant.

“Perry was just voted the national wrestling capital of the world,” boasted Hodge. “We have won 29 state championships and [had] 124 state champions, more than any other place in the country. You know being a small town of about 6,000, how we keep coming up with state championship after state championship year after year is beyond me.”

As a nineteen-year-old straight out of high school, Hodge was at the time the youngest wrestler ever to represent the U.S., placing fifth at the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki in the freestyle competition.

From high school, Hodge found a spot on the wrestling squad at the University of Oklahoma where he went onto to win three NCAA national titles. It was in university that the Hodge toughness first emerged. Ineligible to compete his freshman year, Hodge went undefeated his remaining three years at Oklahoma, winning 46 matches. Amazingly, he was never ever taken down to the mat from standing position.

In 1956, he represented the U.S. in the Olympics in Melbourne, Australia, winning the silver medal in the freestyle competition after losing a controversial match to Nikola Stanchev of Bulgaria in the gold medal match. Even the loss couldn’t dim Hodge’s rising star as he graced the cover of the April 1st, 1957 issue of Sports Illustrated.

After university, Hodge went into amateur boxing.

“I thought I was going to coach and teach for a while but I went to work for a mud company in the oil fields in Wichita, Kansas,” recalled Hodge. “They told me as strong you are you’d be a good boxer. I started going to the gym in the afternoons and hitting the heavy bag and the first thing you know they’re getting me two or three fights a week.”

Just like wrestling, Hodge excelled in the amateur ranks of boxing, winning the national Golden Gloves tournament. Hodge is the only man ever to go undefeated in amateur wrestling and amateur boxing.

“I won the regionals in Wichita and then I went to the tournament of champions in Chicago and I won it all. I had 26 knockouts in a row. Then I go to the nationals in Madison Square Garden and won there. So then I get back and they’re blowing me full of smoke saying I’m going to be the next world champion after (Rocky) Marciano.”

Hodge turned pro but quickly quit the boxing circuit because he wasn’t making any money.

“I had ten pro fights and won eight of those, and didn’t get paid. I told ’em I could have all the fights I want for nothing in Perry, Oklahoma. So I quit boxing and I called up Leroy McGuirk out of Tulsa, Oklahoma to wrestle professionally in ’59.”

McGuirk’s NWA-affiliated office was where Hodge had his greatest fame. While the New York and Los Angeles territories at the time featured more heavyweights, McGuirk’s sleepy circuit based out of Oklahoma and Arkansas focused on the junior heavyweights. McGuirk, a former NWA Junior heavyweight himself, liked what he saw in Hodge and built his promotion around him.

Within nine months of his pro debut, Hodge defeated Angelo Savoldi on July 22, 1960 in Oklahoma City to win his first of seven NWA World Junior Heavyweight titles. From 1960 to 1976, Hodge travelled the world squaring off against the top wrestlers in all of the NWA territories.

“I was recognized by all the organizations, and when I heard there was a junior heavyweight wrestler somewhere, I went to your area or district to show the people what wrestling was.”

Hodge often wrestled outside of his weight class, taking on some of the biggest stars of the era.

“I wrestled the Assassins. The Great Bolo. I wrestled Jack and Jerry Brisco. I wrestled Dory Sr., Dory Jr. and Terry [Funk]. Over the years, I’ve had the opportunity to wrestle Bobo Brazil.”

Of all the opponents he’s ever faced, Hodge counts “Mad Dog” Maurice Vachon as his toughest.

“One of the toughest was Maurice,” admitted Hodge. “I wrestled him for Verne (Gagne) in Nebraska. What a great athlete. You never fought someone (as tough as him).”

Through his epic battles with Hiro Matsuda, Savoldi and Monroe, Hodge established himself as the elite junior heavyweight in the world. His Olympic and collegiate career instilled instant credibility in the title and in the sport as Hodge single-handidly carried the junior heavyweight division during his storied career. It’s because of his hard work and trailblazing efforts that many wrestling historians argue he layed the groundwork for today’s junior heavyweights to find a niche in the sport.

It seems only fitting that it was an auto accident and not an opponent that put him down for the count for the last time. On March 15, 1976, Hodge suffered a broken neck in a car accident that nearly took his life.

“It got cold and I turned the heater up and I fell asleep. I hit this bridge and turned upside down. My car was on its rooftop going along the rock banisters and every time it hit one I could feel my teeth and neck break. My first thought was ‘God how much more can I take.'”

“I’m waiting for the car to come to a stop and hoping I don’t hit anybody,” continued Hodge. “It’s like 3 a.m. and then all of a sudden my car went off the east edge of the bridge down into the water and the water covered it. As I lay there I felt this water gush over me. I said to myself this was an awful way to go. I got out through the dash window, although my car was bent down to the dash and the seat, you can’t imagine what little space there was but I got out through there and swam to the shore.”

Hodge was lucky to be alive. Doctors told him if he took one more serious bump on his neck that he would be paralyzed for life. Hodge never wrestled again.

Hodge found life on the road taxing and came to hate the travel associated with pro wrestling.

“I enjoyed (the travel) for lot of years, probably 13 years I enjoyed it, but then it got to be a long trip to be getting from here to there either by car or plane, it’s wasted time. I didn’t enjoy getting hurt and I got hurt many times. I got cut in Oklahoma City and had 140 stitches in my right leg. I’m off four weeks and I come back to wrestling and get my big toe broke fighting Dory Jr. in Louisiana.”

Still, Hodge has no regrets about his career and maintains that had it not been for the auto accident he would have wrestled for a lot longer.

“I still would have been hanging on today in some shape or form,” laughed Hodge. “Terry Funk is still going today. What’s really great about wrestling is you take a lot of lumps and bumps but you’re not getting hit in any of your vital organs. Wrestling can go much longer than other sports.”

Unlike other veterans from the ’60s and ’70s, Hodge keeps a close eye on today’s product on TV and as a talent scout for the WWF. Looking at the current crop of young talent, Hodge is impressed by one wrestler in particular.

“There’s one young man that’s doing super that reminds me of me and that’s Kurt Angle. He can mix it up with the big boys.”

A grandfather of nine, two of his grandsons are currently competing for Perry High school, as three generations of Hodge boys (including Hodge’s son Danny Jr.) have wrestled on the team.

“Now, I’ve got two grandsons on the wrestling team this year, one’s a senior and one’s a freshman.”

FEATURED LINK