When it comes to the world title, sometimes it’s the belt that makes the champion, while other times it’s the man that makes the belt (think Bret Hart during the WWF’s mid-’90s doldrums). But Jack Pfefer did things a little differently.

This is the story of the Bobby Bruns-Orville Brown feud. Or, how to make a world heavyweight championship in just a few easy-to-follow steps.

Pfefer was no stranger to the world title, having brutally snatched it from the whimpering hands of Danno O’Mahoney and the Trust with the help of the dangerous Dick Shikat in a bout that made international headlines. See some of it for yourself below:

He’d then launder the title before the Trust could seize it in federal court, finally cashing out both the belt and its holder (Dave Levin, another Pfefer prodigy) to Toots Mondt for re-entry into the fold in major league pro wrestling.

It was a nice piece of business that suited almost everyone involved — unless their last name was O’Mahoney, Bowser, or Curley, of course.

Bobby Bruns, the Next Sure-Thing

Only a few years later, Pfefer again groomed a pet project for the world title. This time, however, the world title was kept. Rather, it was modified to fit the needs of his promotions. Fortunately, the title wasn’t built around one man but two up-and-coming all-American stars, both enjoying a meteoric rise: Bobby Bruns of Chicago, and Orville Brown, a fast and feisty cowboy from Kansas.

A handsome youngster from the Chicago suburbs, Bruns was the type of All-American babyface that promoters like Pfefer dreamed of. Bruns arrived on the scene in 1932, originally wrestling under the name “Bobby Burns” to help avoid confusion about spelling errors by local fans (but much to the chagrin of historians who can easily get him confused with Bobby Burns, a popular middleweight wrestler in Utah during the period).

Soon. However, he switched to Bruns, and his career in Midwestern rings began to climb.

By 1937, Bruns had made the main event scene, famously challenging Everett Marshall for his world title at Public Hall in Cleveland, Ohio, on June 1st. Marshall retained as Bruns was severely injured in the match, reportedly suffering broken vertebrae at Marshall’s hands.

However, traction and a painful rehabilitation didn’t keep Bobby Bruns down and he eventually regained his position as a leading title contender. He’d get it on November 10, 1939.

But, was it a real world title? Sure, just not a heavyweight title.

The Birth of a Heavyweight Champion

Bruns was awarded his diamond belt from Connecticut state senator Albert Eccles in Bridgeport after defeating Brown. The title, previously the Connecticut version of the World Light Heavyweight Championship, was a hot potato won by Steve Passas, George Becker, Karol Krauser, and Dave Levin, all during 1938/9.

But the new designation by Eccles indicated the title was now a heavyweight title, with Bruns the worthy kingpin based on his dominant winning streak (and victory over Brown, his leading rival), popularity with local fans, and the promotional ambitions of Jack Pfefer.

However, the title also helped Pfefer accomplish another goal that brought him personal delight: attacking the credibility of Jim Londos, the reigning NWA champion. Bruns had been positioned as a rival to Londos by Pfefer, and the diminutive Pole used his press contacts to help fluff up Bruns’ title claims and accused the Greek idol of screwing over Bruns.

Even the title’s story was dressed up, with Connecticut state senator Eccles becoming a US senator from New York State and the belt presentation at Madison Square Garden and not lowly Bridgeport.

Was it true?

No, not really.

But as historian Tim Hornbaker so eloquently puts it, “wrestling is a battle of press agents,” and in 1940, few were as effective as Jack Pfefer.

In reality, Eccles wasn’t even a state senator at the time; his brief tenure having run from 1935 through 1936. Still, his “authority” was precisely what Pfefer wanted— a whiff of legitimacy to the broader world and very little else.

Brown’s Quest for the MWA Crown

But the Brown-Bruns feud wasn’t over one world title — it was about two.

Bruns also defeated Brown in Kansas City for George Simpson’s “world title,” another version of the same story told in Bridgeport just a month prior. Of course, the match was never billed as for a title, so Simpson likely decided to use Bruns’ Connecticut world title to suit his promotional ambition.

The Midwest Wrestling Association was an Al Haft creation. Haft, Columbus, Ohio, wrestling kingpin, had created a sanctioning body to help prop up his rival claimants to the established championships hoarded by greedy promoters in New York, Chicago, Boston, St. Louis, and Los Angeles. The most famous of Haft’s names were junior heavyweight Joe Banaski and heavyweight “Tigerman” John Pesek.

The formula worked like a charm, and by the end of the 1930s, the concept spread widely, thanks in part to Haft’s critical role in the Independent American Wrestling Promoters Association, the “Little Trust,” of which Simpson was a member.

But by 1940, Simpson had started a war, and he needed all the firepower he could get — and a world title is a hell of a firework.

In January of 1940, Simpson started promoting in St. Joseph, Missouri, with his star Brown leading the way, the established seat of popular local promoter Gust Karras. Karras had deep connections and powerful friends in wrestling and the local St. Joseph community, where he had established himself as a popular and reputable promoter and wrestler.

Karras also maintained a strong friendship with Pfefer, who, by 1940, was providing Karras with talents like Seelie Samara, Slim Zimbleman, and Karol Krauser. Karras relied on his ace in the hole, feared shooter, and former Northwestern and Oklahoma A&M college standout, Roy Dunn. Dunn, also a former Olympian, had a tough reputation.

Dunn himself would also become a world champion in 1940, with his title bestowed upon him by the newly-formed National Wrestling Alliance (NWA), which he held until his retirement in 1957 after more than 2,900 matches. Throughout that time, Dunn would challenge (but consistently balk when accepted) Brown and his successor as world champ (of the NWA, the National Wrestling Alliance, but not the Dunn one … simple stuff, huh?), Lou Thesz.

Even more confusing, Brown would hold another version of Dunn’s, the Iowa NWA title. It’s enough to make your head hurt.

Anyway, back to the story.

Orville Brown, for his part, was no slouch. The Kansas cowboy grappler had established himself as a top contender in the Midwest.

Brown started his career as a Pfefer star out East before quickly rising to the summit of local wrestling as the Kansas Heavyweight champion. Just a few years into his career, Brown was already positioned as a future world champion alongside names like Chris Zaharias and Yvon Robert. Brown was skilled, young, and handsome, and he was the idol of Kansas and Missouri mat fans.

The Brown-Bruns combination wasn’t just a series of technical bouts between two popular stars; it was a blood feud.

The pair rematched on March 28, 1940, though it ended in a draw when both were knocked out simultaneously. Following the match, Bruns stated he was done with Brown due to having already beaten him for the belt in January, though the Texan’s rough tactics were another bone of contention from Bruns.

Bruns sought to duck a rematch with Brown at every attempt, claiming the Texan was no longer a challenger after the double knockout in their previous meeting. The protestations of Bruns were partly storyline, part fact, and really were the exasperations of a world champion from a dangerous contender and a difficult-to-handle, jealous sometimes-friend.

Promoter Simpson continued to play up the simmering tensions, presenting Bruns as the traveling champion to Brown’s determination to finally get his hands on the crown after falling short for so many years.

Think Jerry Lawler vs. Curt Hennig for the AWA title, and you’re in the ballpark.

The rematch finally came on June 13th in Kansas City, when Bruns saw his luck run out — and Orville Brown saw his star finally shine brightest in the wrestling sky. The match was a seesaw three-fall affair, with Bruns getting the upper hand in the first courtesy of a backdrop. But Texans are a tough breed, and Brown powered back in the second with a piledriver, one of the newer, more devastating moves taking over the scene by 1940.

The third fall was never in doubt. Bruns, rocked by the concussive force of the piledriver, was barely able to defend himself, lasting just three minutes before Brown secured a pin and his first world title.

Brown had proven to himself, Bruns, old manager Pfefer, promoter Simpson, and all the Central States fans that he was the real deal, and now the MWA World Heavyweight Champion.

He was off to slay more dragons.

But the title feud between Bruns and Brown was no one-off — far from it.

The whole Bruns-Brown production was such a success that Pfefer would recreate it some seven years later, only this time the belt was a new “world heavyweight championship,” which bears Pfefer’s name for posterity. The wrestlers were two junior heavyweights looking to establish themselves in the world of the wrestling giants: Buddy Rogers and Leroy McGuirk.

For their part, Brown and Bruns would square off in title affairs countless times over the decade, with the pair swapping the title in 1946 and 1948. Bruns would even challenge Brown for the NWA World title in Kansas City. Brown retained the title by winning two out of three falls.

Brown’s World Comes Crashing Down

And then, Brown’s world came crashing down on November 1, 1948, when a car accident ended his career prematurely. But while Brown’s injuries were catastrophic, those of his passenger were less severe.

The passenger’s name? Bobby Bruns. The reason for the drive? They had just wrestled in the main event the previous evening in Des Moines.

Bruns would make an unexpected appearance at ringside just two weeks later, surprising fans with his Lazarus-like recovery after what should have been a double fatality. Brown, for his part, eventually got released from the hospital on the day of Bruns’ appearance, though his recovery was less miraculous, his in-ring career over.

Brown would turn to promoting, joining Simpson as a Kansas City promoter and a member of the NWA. Bruns would continue to wrestle occasionally but found more success behind the scenes as a matchmaker, booking agent, and promotional associate. Bruns’ greatest impact on wrestling is likely the role he played as an official representative of Hawaii promoter Al Karasick on a breakthrough tour of American professional wrestlers in Japan in 1951, which would lay the groundwork for future tours and the eventual explosion of the sport in the years that followed.

And it all started with a blue-chip prospect from Chicago, a madcap manager with a gift for pulling things out of thin air, and an ex-state senator looking for one last shred of relevance.

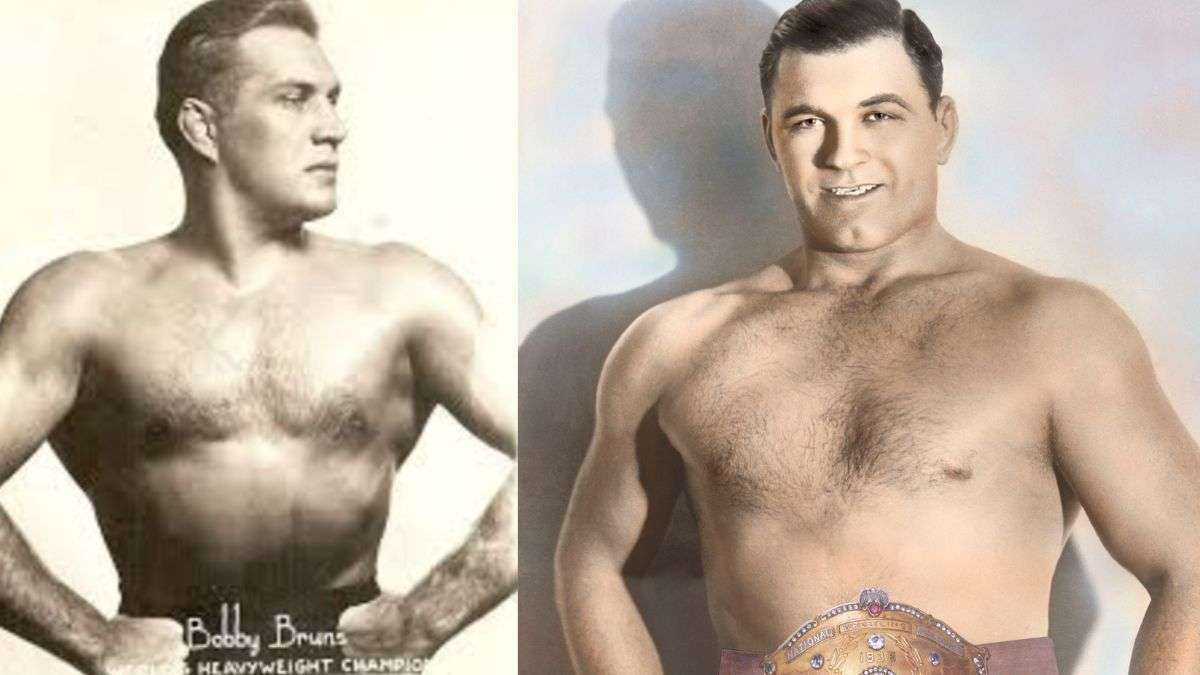

TOP PHOTOS: Bobby Bruns and Orville Brown

RELATED LINK