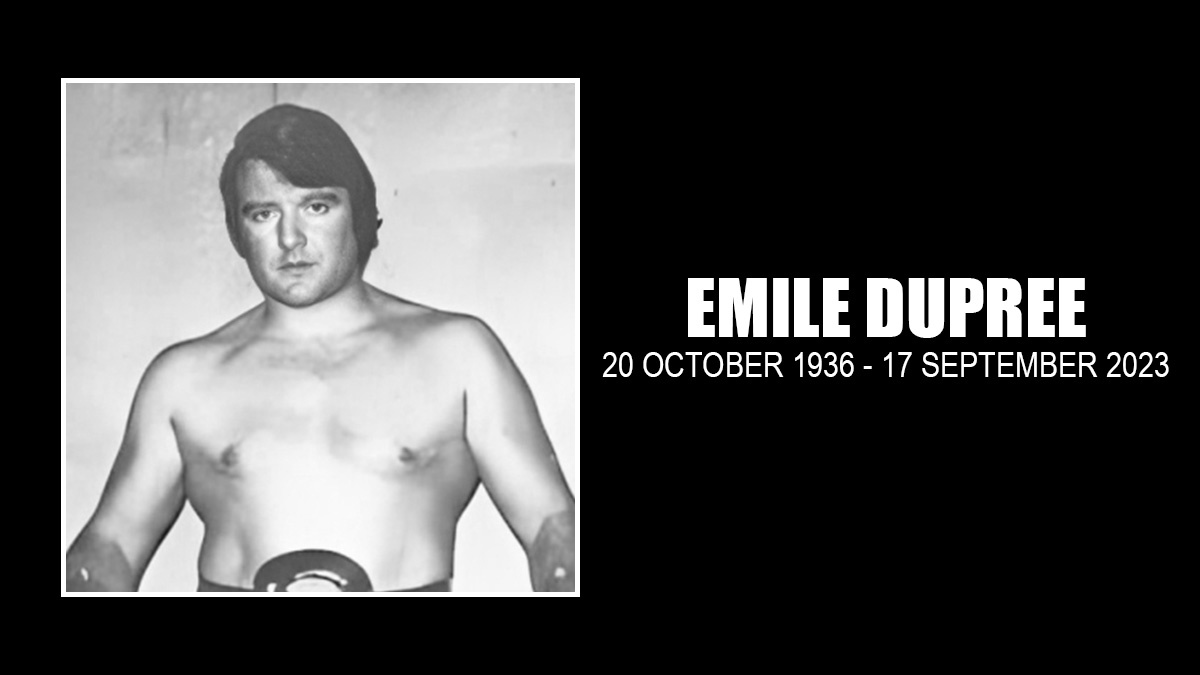

Emile Goguen, who wrestled as “Golden Boy” Emile Dupree or Dupre, and later promoted in Atlantic Canada for decades, has died. He was 86.

There are truly two stories to tell in looking back on his wrestling life. First, he was a babyface who headlined in many places across the United States and Australia, learning his trade in the ring and behind the scenes. Then he became a promoter, running a summer territory that drew all kinds of talent for the setting of the Maritimes — beautiful scenery, smaller towns, shorter drives, fishing — as much as the paid work itself.

And it all worked out just right.

“Everything seemed to fall in place, no matter where I was or what I did,” Dupre said in 2006. “I knew you can’t be Gorgeous George, you can’t be Buddy Rogers, you can’t be Pat O’Connor; you’ve got to be who you are and do whatever it is they ask of you. That was my career and everything went well. That was the bottom line, right there.”

This is his wrestling story. [See also the promoting story.]

His story begins on October 20, 1936 in Shediac, New Brunswick, born to Gaetan and Taryn Goguen, who had four other sons and three daughters. Young Emile grew into a 6-foot, 225-pound man, beginning to lift weights in his garage when he was 13. Goguen attended Sacred Heart of Marie School, which is now known as Francois Bourgeois School. He never graduated from high school, having missed time to earn money for the family, and then himself. “I was poor, very poor. There’s a lot of explanation on things that happened. My father went, my mother went, I was on my own trying to make it. But when wrestling came along, boy, that was the best thing that ever happened to me.”

He’d seen some pro wrestling, and goofed around on Parlee Beach with buddies, but hadn’t considered it as a career. Instead, he was a teen working on pulp boats in the wharf at Pointe-du-Chene, earning nine cents an hour.

In Shediac, he met Fred Bourque, who was a former Mr. Montreal and Sgt-at-Arms at the local Royal Canadian Legion, and Bourque gave him some early wrestling instruction. Then Emile got to see his first live pro wrestling in Moncton, headlined by Bull Curry against Bull Montana, a friend paying his way in.

In 1956, Gerry O’Brien, who ran the fair in St. Stephen, was promoting pro wrestling out of Saint John, New Brunswick, and needed a few more local hands. Dupre, who worked out at the YMCA in Moncton, was suggested to him, so O’Brien hired him for a reported $200 a week. Dupre debuted at the Saint John Forum against veteran wrestler Ray Walker on June 28, 1956. Two veterans, Vic Butler and Reggie Richard, took a liking too him and further schooled him.

O’Brien wasn’t truly the promoter though, as Tony Santos, the promoter in Boston, had arranged the tour, which including boxing bouts and wrestling matches.

Dupre picked up the story:

Tony Santos saw me, I was working out, I was a bodybuilder, as a matter of fact, I looked better than anything he had on the card. I was still going to school. So he says, this was late June, school had just finish, he says, “Would you be interested in taking a trip to Boston with us?” I said, “Holy geez, yeah.” I didn’t have a job anyway. So that’s exactly what I did. I went to Boston.

Santos ran smaller towns and Paul Bowser was the big promoter and controlled the Boston Garden. Dupre, with newly bleached-blond hair, worked on Santos’ small shows at summer tourist communities, like Riviera Beach, Massachusetts, and Old Orchard Beach in Maine.

Dupre was introduced to Bowser, and jumped to the bigger platform. “Tony Santos was an Italian fella. He wanted to shoot me when he found out that I was going with this other bunch. Holy geez. Three months later, I was in the Montreal Forum and I was in Madison Square Garden. Right that quick. Everything happened to me in six months. I wasn’t even 20.”

There were always stars to get the rub from. One was Yvon Robert. “When I first went to Montreal, he used to be in my corner as my manager,” said Goguen. It was short-lived as the Maritimes were calling Goguen home. But was enough time with Robert to see his legend: “When we walked into a restaurant somewhere, and they saw him, it was like the Pope came in. Oh, the people loved him.”

Similarly, Goguen learned from Whipper Billy Watson. “To me, he portrayed more of a politician type of wrestler,” he said. “What he had going for him was his talking, his speaking. He looked smooth, with his black robe.” There were lessons learned from The Whip too, including the importance of publicity photos.

Goguen was once asked, “What made you a great hero, a great babyface?”

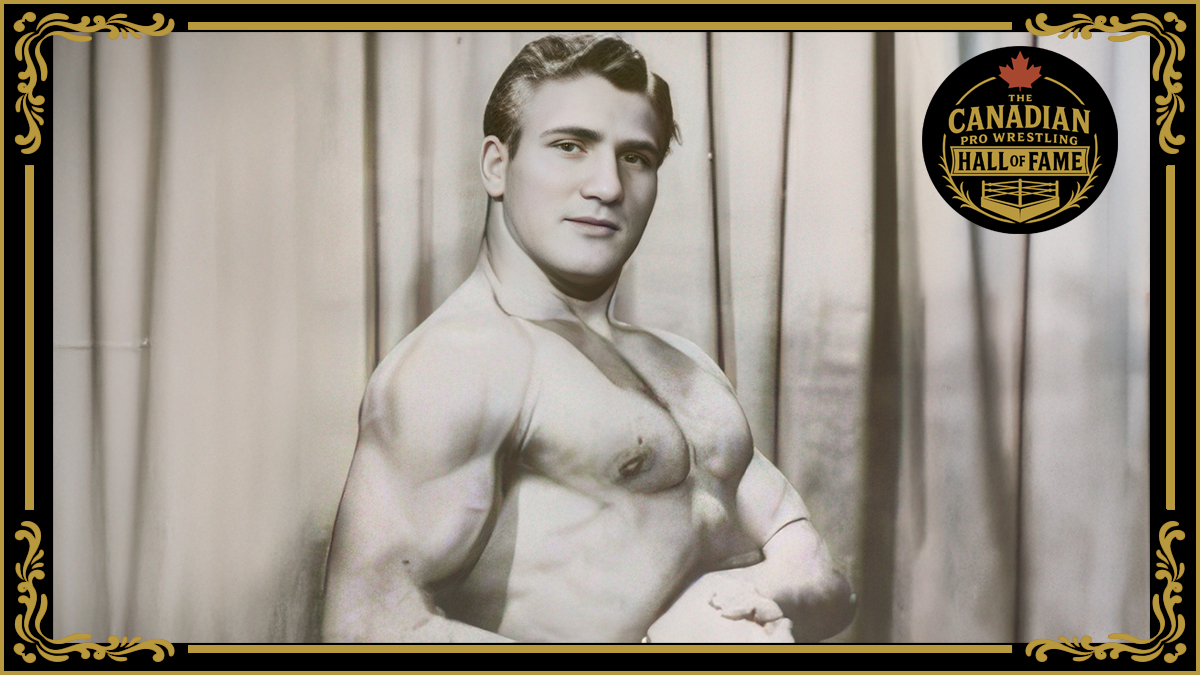

“I was lucky to have, I hate to say this, but I was sort of a handsome guy and I had a good body,” he said, admitting that his unique New Brunswick-accent, with its hint of French, could have helped. “In wrestling, anything that’s a little bit different sort of helps you. If you have an accent or you’re different from this other guy or from another guy. I think it gives you a little bit of a boost.”

Athletic and good-looking, Dupre could do “kip-ups, nip-ups, stuff like that, some of the fancy stuff,” which stood out at a time when much of pro wrestling in the major centers was dominated by plodding big men. Another big move was the mule kick for Dupre.

Golden Boy had no problem bringing up some of the names that he modeled himself on:

I’d say every wrestler sort of idolizes somebody. I used to like Pat O’Connor, I liked his style. I did a lot of his stuff, like the kip-ups and all that kind of stuff. I had a lot of respect for Verne Gagne. I used to watch him. I used to like the way he did things. I used to like Killer Kowalski‘s style too. I used to like the way he wrestled. I think every wrestler in the business has somebody they look up to, that they want to imitate. Just like myself, that’s the way I did it. I had a long career.

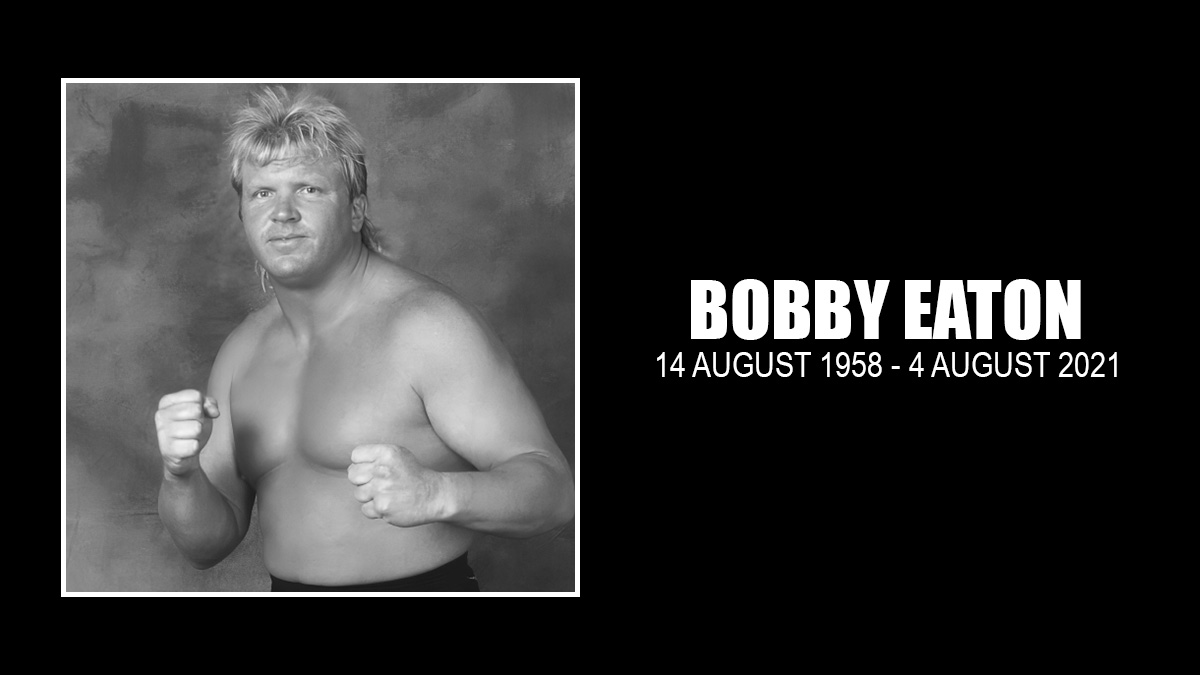

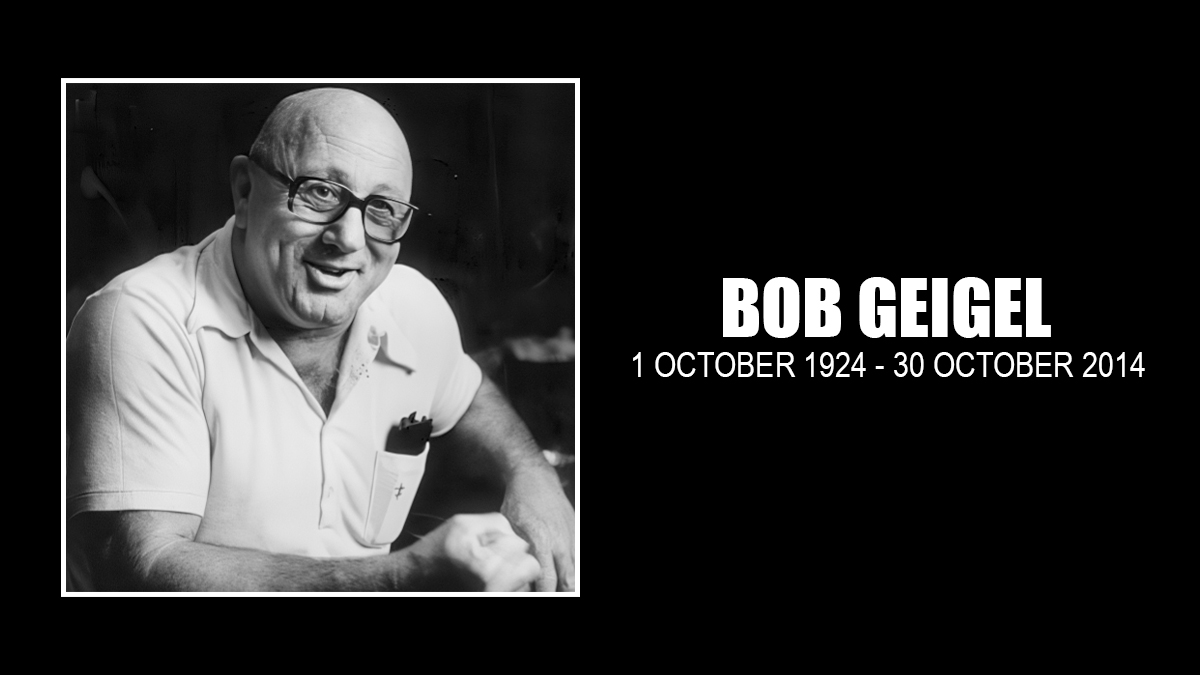

Bob Geigel wrestled Dupre in New Brunswick early in both of their careers. “He was good when he started. He was a very talented guy.”

Les Ruffin was a key figure in Goguen’s life. They met in Boston and Ruffin acted as a mentor of sorts. It was Ruffin “who really taught me the ropes on that kind of stuff — don’t ever burn any bridges. If you don’t where you’re at, give an excuse that you’re leaving, but that you’d like to come back some time. In that case, he said, you didn’t insult anybody, you didn’t tell them to go eff themselves or anything like that.”

Ruffin was Goguen’s connection to Verne Gagne in Minneapolis, or Jim Barnett. “He was the best adviser I ever had. He became friends with me. We used to have a few beers together. We got to be friends. Anytime I needed help or advice, I’d give him a ring. He’d go to bat.”

Detroit, promoted by Johnny Doyle and Jim Barnett (who also ran Indianapolis), was so important to Dupre, in part because the promoters believed in him. “Then from there, I went to Australia with them. I followed them two promoters.”

Dupre was a part of the first run of Doyle and Barnett in Australia, along with names such as Killer Kowalski, Dominic Denucci, Buddy Austin, and Dale Lewis.

“It was really a small crew. I’m going to tell you something, we just went on doing television for six weeks. That’s all we did was TV. When they opened up the arenas to this new show, they were four deep almost a quarter of a mile long. All the arenas were sold out, unbelievable business,” recalled Goguen. “I remember Johnny Doyle writing the cheque. ‘I don’t know why a man of my age would sign a cheque of this size!’ This was the investment for Australia. It was only $50,000, it wasn’t a million dollars. But what an investment for them, the money that they made.”

The trips were long: “I remember flying from Sydney to Perth. They had a big show there with 8,000 people. Me and this other guy, we were in the ring maybe 15 minutes. We were joking around, ‘What a trip for 15 minutes and a shower — 4,000 miles!’ It wasn’t that hectic, really.”

As with Ruffin, Barnett believed in Goguen and promoted Golden Boy on his own shows and to others. “I’ll say this for him, he was a good promoter. He knew his stuff. I started working for him back in 1956. I was in Chicago when they used to have the Marigold Arena. That’s how I first got to work with him. I worked for him many, many times after that. He was part of the Omaha territory, he’d send me to Omaha with the Dusek brothers. Then when [Roy] Shire and Ray Stevens opened up San Francisco, well, that was a part of Doyle and Barnett also. They went me there. That’s how I got connected to all these different territories. A smart, smart, smart man.”

Goguen studied along the way, which would help him in his own promotion.

There were so many places Dupre was a major player, but there was always a first time. “I remember the first guarantee I ever got, for $300, it was Jim Crockett [Sr.] in Charlotte, North Carolina. I had never been sent a telegram that I was going to be guaranteed a guarantee of $300 a week. I took it and I put it in a frame, I framed it I was so excited!”

Goguen had a bit of a wandering spirit, wanted to see the world. “I’ll tell you, I was a lucky guy. One door would close and another would open,” he said. It was as simple as calling Rod Fenton, who was promoting in Vancouver, and hearing, “Yes, we’ve heard of you. I think we could use you.” In that case, Goguen wasn’t offered a guarantee, but was told he’d do okay. “Sure did! They teamed me up with Don Leo Jonathan.” That was the start of a great friendship with the Mormon Giant, who’d end up working often for Goguen’s promotion.

The in-ring days of Emile Dupre didn’t completely come to an end when he began promoting, helping Cowboy Len Hughes in the 1960s and then on his own, but it wasn’t feasible to do both at once, Goguen said. “I was wrestling myself, and then all of a sudden, I said this is more important to me to do the promotion, booking the towns, and taking care of things, rather than me being in the ring. That’s why I stepped aside.”

Through it all, Goguen kept himself grounded, returning home to Shediac, staying in touch with old friends, investing in the community, primarily through real estate.

He and his wife, Paula, had two children, Geoff — who wrestled as Jeff Dupre for a short while — and Rene — who began at age 14 in his father’s promotion as Rene Rougeau and would become one of the youngest WWE stars in history as Rene Dupre. He also has a daughter from another relationship.

Compared to many of his colleagues, Emile Dupre kept a fairly low profile. He didn’t attend wrestling conventions, go to reunions, do shoot interviews or crow about his storied career. Even when there was a major celebration of the Cormier family — Leo Burke, the Beast, Rudy and Bobby Kay — in Memramcook, NB, in 2006, the always-busy Goguen only came by for a short visit.

He continued to maintain his various investments in and around the province, and traveled to Florida every winter. The days of the constant travel during his active in-ring days were done. Rene Dupre said his parents never visited him when he lived in America. “My dad’s old school. Even when I was in the United States, my father never came to visit me. Nah. I had to go visit them in Florida.”

Goguen had been in declining health for some time. Further details on his passing on September 17, 2023, are not known at this time.