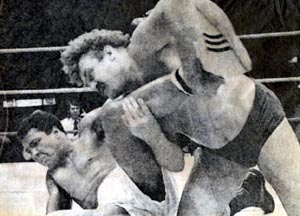

One of the proudest moments in the ring for Les “Buddy” Wolff, who died on July 11, 2017, after a lengthy battle with dementia, came during a series of bouts in against the WWWF champion.

He’d been in the wrestling business for a number of years, and knew his stuff. A product of the Minnesota training ground of Verne Gagne, Wolff could handle himself, even if everyone didn’t think he could.

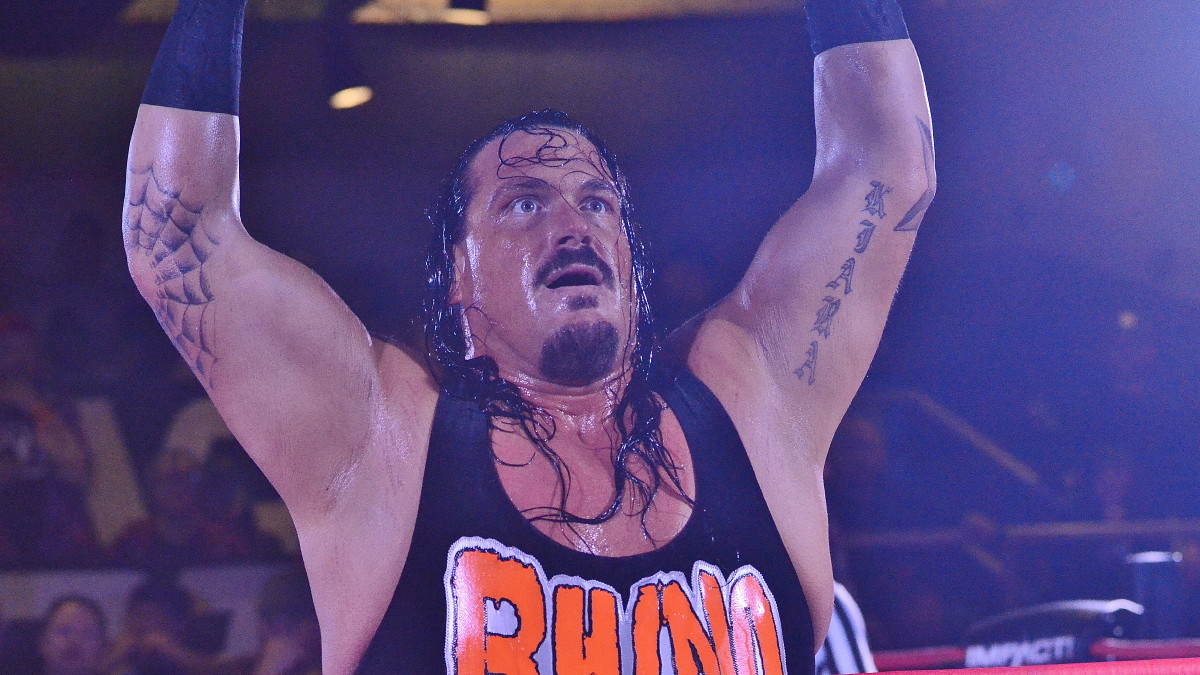

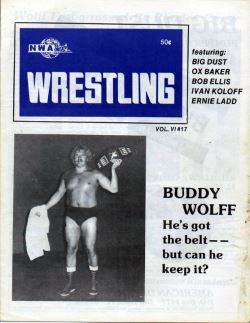

Buddy Wolff

“When I was in New York, one of the oldtimers working in the office, when I came out of the ring, he said, ‘You can’t use that wrestling out here. The people won’t buy it. They’re used to us bringing in big, monstrous wildmen. The wrestling that you’re trying to use is not going to draw,'” Wolff recalled in 2006.

He proved them wrong.

“I sold out Philadelphia with Pedro Morales four times in a row, I sold out Albany, Scranton, PA, Harrisburg, PA. I never won a match [with Pedro]. Just with interviews, I sold out with Pedro. They stopped the match and gave it to him because of too much blood. We came back a month later … and an hour-and-a-half before the match started, it was sold out already.”

It was hardly the only place where Wolff made believers out of skeptics.

In Tampa, Florida, he faced Dusty Rhodes 13 times in a row, and according to Wolff, only two matches didn’t sell out.

It was about being believable, said Wolff. He’d learned from Gagne, styled a lot of what he did after Johnny Valentine, and considered Gene and Lars Anderson to be key mentors.

“For most people, that can’t work and do a lot of wrestling. You get a match or two or three and you’ve seen all you want to see of them. There’s no mystery there anymore. There’s a kick to groin, some eye gouging and hair pulling, choking. How many times can you see that? You can’t go back every week for three months.”

Like Valentine, Wolff lived by the ethos that you might not believe wrestling is real, but you will believe in me.

“I had matches where guys would come up to me and say, ‘I know this wrestling isn’t all that it’s cracked up to be, but I really believe in you, man.’ That’s just doing your day’s work. If you can elicit that response, then you know you’re doing your job well.”

Born April 11, 1941 in Blue Earth, Minnesota, Wolff worked at a cast-iron foundry after high school, but needed more. He enrolled at St. Cloud State University in 1960. There he was a two-sport star, a lineman at 6-foot, 220 pounds for the Huskies, and a wrestler who was considered a possibility for the U.S. team at the 1964 Olympics.

Choosing semi-pro football over staying amateur for the Olympics, Wolff did that for a while but needed more. His education degree and part-time teaching was one thing, but not enough.

One of his teammates at St. Cloud was Larry Heiniemi, who wrestled as Lars Anderson. He put Wolff in touch with Verne Gagne and finally Wolff had found his calling.

But all those other experiences helped to round him out, he said. “Basically, if I hadn’t wrestled, hadn’t played football, hadn’t done all those things, I couldn’t go out and make that up in front of a TV camera, whereas a lot of guys can’t.”

Minnesota historian and long-time fan George Schire knew Wolff for decades. “He was one of the nicest guys out of the ring. Got his early training from Verne Gagne and made any card he was ever part better because he was on it.”

A Florida program from 1977.

In celebrating Wolff, who was sometimes billed as “Beautiful” Buddy Wolfe and who worked as Spoiler #2, the words “jobber” or “journeyman” might be thrown around, or “carpenter.” The fact is that in the territorial days, the journeymen and the carpenters were the ones that build the stars, made them look like a million bucks while not looking back in their own right. The valuable assets would win some, lose some, but always have work. That was Wolff to a “T.”

So when it came to a major event, with Muhammad Ali facing off against Antonio Inoki, it’s no surprise that Wolff was called upon. Promoters could trust him.

To promote the bout with Inoki, Ali was scheduled for three exhibition bouts against three opponents at the Chicago Amphitheater that aired on ABC’s Wide World of Sports. Ali faced Kenny Jay, and beat him and then Wolff. The rules stated that Wolff, his hands bare, could not strike Ali, whereas Ali had his boxing gloves on and could swing away.

The Associated Press report from the bout read, in part:

Wolff even made referee Verne Gagne work hard as he tore after Ali, shedding left jabs as if he wore a catcher’s mask, picking Ali up like a bag of potatoes and smashing him to the canvas, and twice dropping the champ over his knee in what is known as the “backbreaker.”

Gagne was all over the ring ready to count Ali pinned as Wolff, smothered him on the floor. But Ali seemed indomitable, always managing to crawl to the ropes on his belly and avoid a pin.

Ali also displaying some wrestling maneuvers, scissoring Wolff around the neck with his legs, flipping him over his head and whomping him with his 16-ounce gloves while he was floored — all according to the rules of the mixed match.

Muhammad Ali and Buddy Wolff.

In the third and final round, Ali unleashed rights and lefts to Wolff’s head. He couldn’t knock him down but opened a gash on the wrestler’s forehead. Wolff, Gagne and Ali were covered with blood.

But Gagne wouldn’t stop the action and Wolff was allowed to bleed profusely until the bell while nearly 1,000 fans –admitted free — jumped to their feet, held clenched fists high and shouted: “Ali! Ali!”

Then things really turned wild for the benefit of the television cameras capturing the show for Saturday’s ABC Wide World of Sports.

Ali’s arm had been lifted as winner and he was in his corner looking down at his blood-splattered body. Wolff charged him from across foe ring like a water buffalo and the champ began raining him with rights and lefts as the ring filled with attendants trying to break it up.

“It was quite an honor for a little old farm boy that when he first heard his older brother listening to a Joe Louis fight coming from Madison Square Garden, asked ‘What are they doing fighting in a Garden?'” chuckled Wolff in 2006.

“I admired the guy. We talked and everything was a very positive thing. I just knew that I had to move a little further in the match than what his handlers wanted. He wanted to move further in the match also, but they were so concerned with him getting hurt. He had three guys with canary yellow blazers that had big bulges under they breastplates that were right outside the door, and right outside the ring. I had to respect that part of it too.”

While Wolff’s fight with Ali comes up often, the other name with which he is most associated with is Vivian Vachon, whom he married in July 1976. [Their relationship is detailed in a lengthy 2013 feature: The life and loves of Vivian Vachon, Wrestling Queen] They were married three years, but had no children.

Wolff had two daughters, Lisa and Alexa, with his first wife.

A Corpus Christi, Texas, newspaper described Wolff in 1976, not long after his bout with Ali: “[B]backstage Wolff was a softspoken, articulate man who said he had found wrestling more lucrative than professional football. Wolff, his blond Orphan Annie locks framing a handsome face, said he flew home to Minnesota every week to visit his girl,” wrote Hilary Hytton.

He stopped wrestling in the early 1980s, and again, took a while to find his calling. He lived on a lake near Hackensack, Minn., and ran T-shirt shops. He tried running a restaurant, Budros, but that didn’t work out. Wolff took work as a silk-screener.

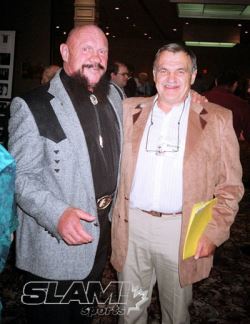

Dewey Robertson and Buddy Wolff at the 2006 Cauliflower Alley Club reunion. Photo by Greg Oliver

Always a creative thinker, Wolff had tinkered with inventions through the years. One night, he watched banners get ripped apart in a gust of wind — particularly galling since he’d worked on the banners — and came up with a flexible bracket that could be mounted with the banner that would move in the wind. The “Banner Saver” was patented and he had found a new calling.

In 2002, he finally made it to the Olympic Games, as he was in Salt Lake City where his Banner Savers were all around town.

Wolff did not make many wrestling-related appearances. “I’m kind of a hermit,” he said in 2006. That same year, he did attend a Cauliflower Alley Club reunion in Las Vegas.

Schire said that in recent years Wolff had battled dementia.

Wolff’s daughter, Lisa Wolff Clausen, posted details to Facebook: “I know he is at peace and is joyous to once again see his family and friends who have gone before him. Here’s to a big Heavy Weight Wrestling Championship match up in Heaven!!!”

She also said that his brain had been donated to Boston University for CTE research.

The funeral service for Les Wolff will be Sunday, July 23, 2017, at 6 p.m. with visitation starting at 4 p.m. at Daniel Funeral Home in downtown St. Cloud, MN.