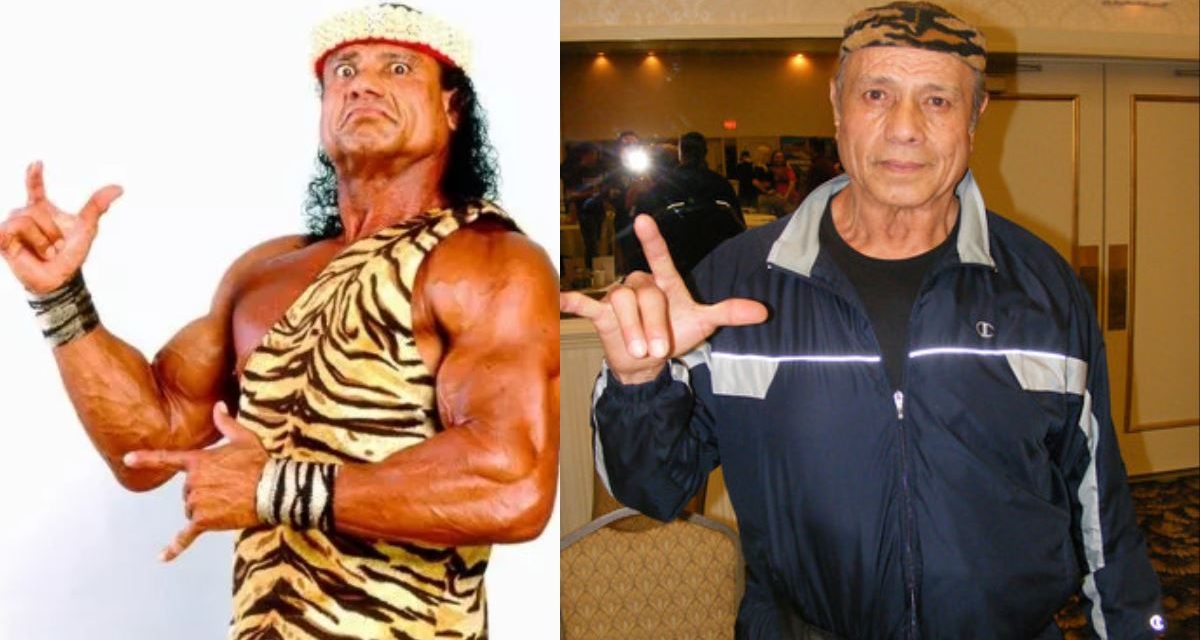

In a move I didn’t see coming, though I’m pleased it did, the district attorney has referred the almost 31-year-old investigation of Jimmy “Superfly” Snuka’s role in Nancy Argentino’s death to the Lehigh County (Pennsylvania) grand jury. This latest development in the long-dormant cold case — I call it pro wrestling’s Chappaquiddick because Snuka’s lack of accountability so closely parallels Ted Kennedy’s — made international news. On Thursday I spoke at length with a producer for a network television news magazine program.

Before analyzing what might happen next, let me first remind everyone that grand jury proceedings are secret. The following is not based on any inside information. Like all of you, I don’t know what actually will happen next.

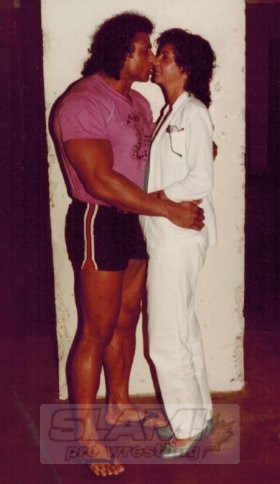

Jimmy Snuka kisses Nancy Argentino

Also, my views here probably don’t perfectly overlap those of Nancy Argentino’s sisters Louise and Lorraine, whose work with me on a 30th anniversary ebook about the case — along with excellent fresh reporting by the Allentown Morning Call — was so instrumental in upgrading “justice denied” to “justice delayed.”

But, really, how could anyone else feel exactly the way the family does? None of us has “walked two moons,” much less three decades, in Louise and Lorraine’s moccasins. We didn’t get blown off by the authorities after a loved one was taken from us under circumstances far less ambiguous than their original public pronouncements claimed. We didn’t watch Snuka walk away, without ever paying a dime, from a $500,000 default judgment against him in a civil case. (At the time of the 1983 incident, Snuka was at the peak of his earning power. Girlfriend Nancy more or less expired, in the motel room they were sharing, while Snuka was off performing at the then-WWF syndicated TV taping in Allentown.)

Now that district attorney James Martin has implicitly acknowledged the flaws in the original investigation coordinated by predecessor William Platt (today a senior judge in the Pennsylvania court system), what’s to be done? I have a theory.

There is no statute of limitations for first- or second-degree murder or voluntary manslaughter. However, there is a statute of limitations for involuntary manslaughter, and it has expired here. And a finding of involuntary manslaughter would be completely consistent with all that is known about the fatal Snuka-Argentino incident.

Snuka’s meandering story about Nancy supposedly taking a unilateral spill when they stopped for her to urinate along the roadside on the way to Allentown is an insult to the intelligence. It’s not even a story, but multiple stories, given the failure of Snuka for 31 years to tell it with the same fundamental details twice in a row. The latest versions were in his 2012 autobiography, which were followed by still additional contradictions in promotional radio interviews, during which ghostwriters and handlers held his hand and tripped over themselves to help fill in the Superfly’s own obvious and painful gaps in testimony. (The Snuka book infuriated the Argentino sisters and catalyzed recent developments.)

What remains is circumstantial evidence without reasonable doubt. The only serious question is the degrees of agency for the fall in which Nancy struck her head against a blunt and stationary object, either on the roadside or, much more likely, in Room 427 of the George Washington Motor Lodge in Whitehall.

From the police incident four months earlier at the Howard Johnson’s motel in Elmira, New York, we can glean that Snuka and Nancy had a stormy, violent relationship. Most would conclude that she was a battered woman. If you prefer, conclude that she was an active participant in a wild 1980s road party scene, full of alcohol and cocaine and other drugs. But even if Nancy made a poor choice of a companion, and poorer choices in her activities with him, there is no legal or moral standard by which she deserved to pay for them with her life, as a result of a discrete episode putting her on the receiving end of violence on the part of a 235-pound professional athlete.

The softest plausible explanation is that Snuka shoved the 23-year-old woman more forcefully than he intended, with tragic consequences. That would be classic involuntary manslaughter.

Would justice, in the largest possible sense, be served by trying a 71-year-old man for a 31-year-old case (assuming the grand jury might proceed to find voluntary rather than involuntary manslaughter)? I am sympathetic to the argument that, sans prosecution, Snuka has paid a heavy and direct price in the last year, even if he never did before. For one thing, the story by Randy Miller, then of the South Jersey Courier-Post (for which Snuka first agreed to an interview but then reneged), has raised awareness in Snuka’s own current home community of this awful and covered-up incident from his past. He has suffered well-deserved reputational damage, and his few remaining opportunities for commercial exploitation of his wrestling fame have dwindled.

A grand jury finding that there are grounds for prosecuting Snuka only for involuntary manslaughter — a process barred by the statute of limitations — would serve the function of providing some closure while also amounting to a way out of this mess for the district attorney.

It is that mess — the accountability of law enforcement officials — that matters more to me at this point than watching Superfly Snuka continue to twist in the wind. In chronological order, the public needs to know what informed the decision not to indict in 1983, and why Whitehall police detective Gerry Procanyn (now an investigator in the district attorney’s office) lied to me about Snuka’s credibility and consistency when I made a 1992 reporting trip to Allentown. (To me, Procanyn not only stated his confidence in Snuka’s peed-by-the-road scenario, but also promoted the blatant falsehood that that was his only explanation, when there were actually many contradictory accounts — to the hospital staff who attended to Nancy, and to the police themselves and Procanyn personally.)

Snuka’s autobiography recounted the rearrival of Vince McMahon in Allentown in 1983, and the promoter carrying a “briefcase” into a climactic meeting with authorities. In a 2008 email to me, mostly about Chris Benoit and other matters, WWE lawyer Jerry McDevitt complained about my reporting others’ recollections of McMahon’s role during the police investigation, and specifically his acting as a mouthpiece for the mostly silent Snuka. McDevitt called it “an odious lie” to “insinuate” anything from that. In light of this week’s grand jury news, objective observers would have to agree that McDevitt’s choice of words was carny bluster, rather than careful argument.

Whatever happens from here, one consequence is rising awareness of domestic violence — a very good thing. SLAM! Wrestling readers are invited to order my ebook collaboration with the Argentinos, JUSTICE DENIED: The Untold Story of Nancy Argentino’s Death in Jimmy “Superfly” Snuka’s Motel Room, available for $2.99 on Amazon Kindle. Those of you without Kindle-compatible devices can get a PDF copy on email with a $2.99 payment, through PayPal, to from direct email PDF orders, also available for $2.99 payment via PayPal to nancyargentino@gmail.com. One hundred percent of the proceeds benefit the My Sisters’ Place women’s shelter and resource center in Westchester County, New York.

The larger lessons of this case are not confined to Jimmy Snuka or pro wrestling. We have confirmation of the devaluing of non-celebrity life, throughout sports culture, in the ESPN commentator job of retired football star Ray Lewis, who paid a six-figure civil settlement after deceiving police in his arguable accessory role in a murder.

We have special confirmation of shabby and backward attitudes toward women in the rape allegations against Jameis Winston (whose investigation was an inconvenient pit stop en route to the Heisman Trophy award ceremony) and Notre Dame and University of Missouri football players (whose alleged victims would commit suicide).

Getting to the root of this issue is one of the goals of my current investigative journalism, in collaboration with Tim Joyce, on the Catholic Church-level problem of youth coach sex abuse in USA Swimming — now the subject of probes by Congress and other federal agencies.

RELATED LINK

- Jimmy “Superfly” Snuka story archive

- Revisiting Jimmy “Superfly” Snuka and the death of Nancy Argentino

- Irv Muchnick’s CONCUSSION INC. website

- Irv Muchnick on Twitter: @irvmuch

Visit Amazon

Last year SLAM! Wrestling republished Irvin Muchnick’s original 1992 article on the Snuka-Argentino case: Revisiting Jimmy “Superfly” Snuka and the death of Nancy Argentino. Complete chronological links to Muchnick’s coverage of the Snuka case are at concussioninc.net/?p=8577.