This past April, during the Cauliflower Alley Club reunion, Sonny King did something he hadn’t done in a long, long time — he talked about pro wrestling.

King, a star in the late ’60s and ’70s, had put his time in the squared circle behind him. He runs a junkyard in south Florida, buying cars and selling parts, and just chopped up a few cars to pay for the trip to Las Vegas for himself and his son, a former linebacker for the South Carolina Gamecocks.

So sitting down and talking about his career for 45 minutes was something new.

“I never kept wrestling in my head,” confessed King. “Before this, this is the most I’ve ever talked about wrestling since I left. I’m being honest here. In fact, this is the first interview I ever gave. I never talked about wrestling, never.”

Memories, good and bad, were dredged up. “You took me places that I hadn’t been in a long time,” he said.

Credit goes to Tiger Conway Jr. for pulling King back into the fold, first with a trip to the industry-only Gulf Coast Wrestlers Reunion in Mobile, Alabama, in March, and then the CAC reunion.

Recently, King has been dabbling with an idea, a promotion called the Ebony Wrestling Alliance. It wouldn’t be exclusively African-Americans, but “just the opposite of what it is now,” he said. “When I find the type of talent I’m looking for, I’ll bring it onto the market.”

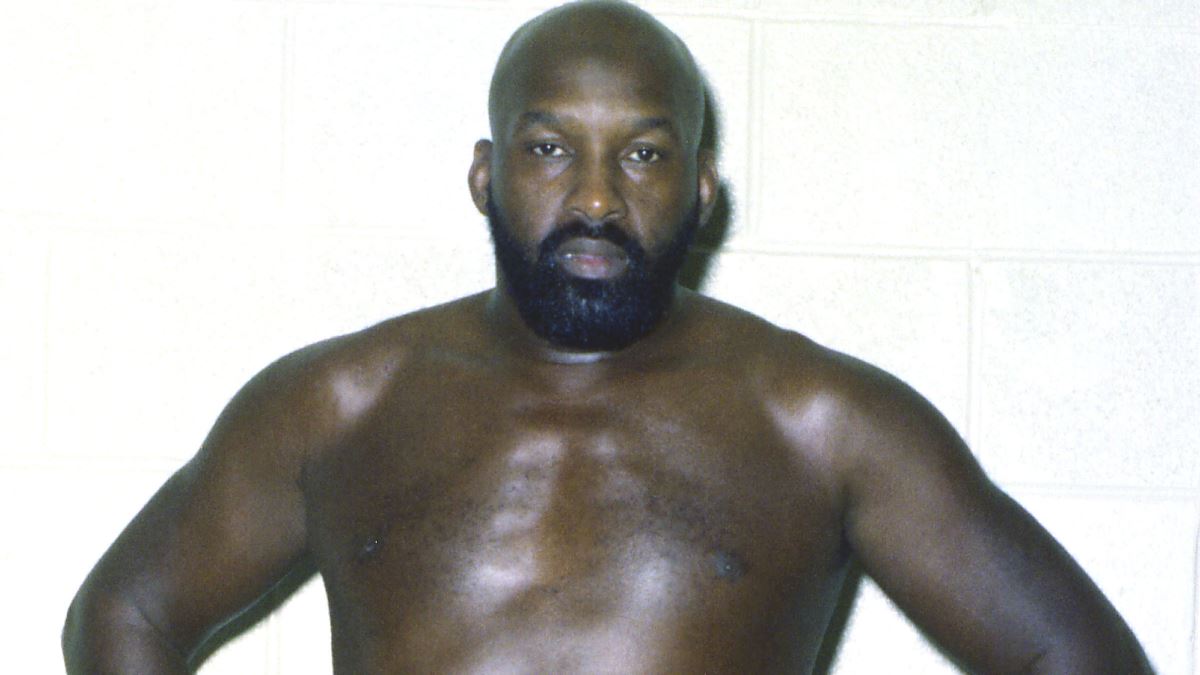

There was a time when Sonny King (Larry Johnson) was one of those talents that promoters were looking for.

Growing up in North Carolina, he wasn’t a wrestling fan., but knew about the bouts.

Instead, it was boxing that caught his interest, and he turned pro. One of the wrestlers he befriended along the way was Ernie “The Cat” Ladd. On one occasion, King was in Montreal for a boxing bout, and Ladd convinced him to come to the wrestling show that the Rougeaus were putting on.

King recalled his initial memories of the behind-the-scenes action. “He and Jacques Rougeau, they wrestled for 10, 15 minutes. Now I’m sitting down in this dressing room, and they’re counting this money. ‘Nah, that’s not right, man.’ ‘Yeah, it is.'”

Jack Britton, who was the promoter of the midgets out of Detroit and a Montreal mainstay (and father of Gino Brito), came into the dressing room, and thought King should be a wrestler. King declined, initially.

“So one day I called him up. He said, ‘You want to go to Detroit.’ I said, ‘I’ll be free to go in June.’ He said, ‘All right.’ So I went down to Detroit, Allen Park is where their training school was. The Sheik was connected with Lou Klein and Jack Britton and their school. And everything else is history.”

Everything came easy to King.

“God, I don’t know how to say this, because it’s almost like bragging, but the competition — and after I understood what it was all about — it was so easy. The guys that had been in the gym forever, they would call me up at my house and find out when I was going to come down and train so they could wait to train with me.”

As a young African-American, King had a lot of mentors in Detroit, including Ladd, Bobo Brazil and Thunderbolt Patterson. The Sheik looked out for him.

Soon, he was a regular at the centre of the territory.

“Cobo Hall was a huge thing in Detroit, that was the big show, so you put the best talent out there,” he said. “The big thing was when you come from Lou Klein’s gym, if you wrestled on a Saturday night in Cobo Hall, that’s it. Everybody wanted to go to Cobo Hall. Sometimes they’d be short for a match and they’d put somebody from the gym into Cobo Hall. I was pretty fortunate. I used to work Cobo Hall mostly every Saturday.”

The potential in King was evident when he arrived in Pittsburgh to work for Ace Freeman and Bruno Sammartino. “Bruno said to me, ‘You’ve got a good size, you’re good in the ring, so I’m going to tell Sheik not to send you up here anymore, and sort of keep you close until you’re ready.’ So I didn’t get no TV, they pulled me off TV and everything else, and they just let me go.”

The first territory that King actually worked was a summer in Ontario for Larry Kasaboski.

“I lived in North Bay, at the Hart cabins,” he recalled. “It was neat, it was neat. [Starts to laugh] I met some nice people over there as well. I worked that whole territory for the whole season.”

King’s most notable run came in the WWWF in 1972, where he teamed with Chief Jay Strongbow to win the WWWF Tag Team titles from Baron Mikel Scicluna and King Curtis Iaukea.

“When I went to New York, I was on my way as far as my career goes. I guess the test was whether I was capable of carrying a full match as a single … especially over there,” said King. “Then with Strongbow, who was a headliner himself, to get with him, he was well established, to get with him, it was like, ‘There it is.'”

During his lengthy career, King worked both as a good guy and a bad guy; after his career ended, he was a heel manager in Memphis.

One of the memorable things about King was his interviews.

“My thing was, irregardless of how it seemed, what I was doing, I believed in it. And the way that I wanted to express it, I expressed what I felt. Everything else works into that part of it,” he explained. “Like when I’m watching wrestling, everybody is screaming and hollering and trying to get a point over. I was never that way. And my reason for never being that way was because if you’re a wrestling fan and you’re interested in wrestling, and I make an interview talking to the announcer, if I talk to the announcer, which is my normal voice, then if you’re a fan, and you’re interested in what I’m saying, you’re either going to turn the TV up or you’re going to ask whoever’s talking to be quiet so you can hear. And that means that I’ve got your attention. … that was my reasoning.”

Or to put it another way, “You can’t scream and holler and say you’re going to pull this guy’s eyes out. You know it’s not going to happen. How many times can you tell somebody the same thing over and over again? And every guy say the same thing in every interview anyway.”

It is obvious that King gave his persona and how he was perceived a lot of thought.

“I’ve always had all kinds of the challenges. The only thing I have to say to ‘Wrestling is fake, wrestling is fake’ is, if that’s your opinion, I cannot change it. All I can say to you is, ‘Anything you see me do in the ring, I can do it right now, right here.’ That ends the conversation.”

If King sounds like a bit of a tough guy, that’s because he was.

Memphis announcer Lance Russell called King “one of the toughest guys I ever saw, on the streets and everything. … Sonny was legendary for how tough he was. He was a streetfighting fool.”

King didn’t dismiss his toughness, but didn’t brag about it either. “They didn’t have one guy they could put with me and say, ‘Beat his ass.’ They didn’t have anybody capable of doing that,” he said, adding that he was “not tough, but I always managed to carry my own weight, where I was comfortable in whatever situation.”

In early 1982, that toughness nearly got him killed.

He had gone to the Charlotte Coliseum from Myrtle Beach to see a friend back from Japan wrestle, but King wasn’t on the card. As he was leaving, alongside a security guard, the police on hand were tossing somebody out.

“When they threw him outside, he came to the security guard. They started blowing smoke at the security guard, right?” remembered King. “I said to them, ‘Man, don’t mess with this guy. The cops are the one that threw you out.’ One of the guys says to me, ‘It’s none of your fucking business nigger.’ Alright. So when he said that, I got him. His friend — there were three guys all total, then the other guys, they stabbed me and left.”

King was stabbed all over: “In the head, in the arm, in the back, and one in the chest.”

Cryptically, King said the assailants just got “southern justice” and he was off work for months. While he didn’t get paid by promoter Jim Crockett Jr., King did get some help from Crockett. “When I went to the hospital, he comes and he says to me, ‘Don’t worry about anything, and if you need something go direct to me, and don’t talk to anybody.’ Fine, that was it.”

When he was back on his feet, King returned to Memphis, where he had been a heel manager in 1978, with Jos Leduc and John Louie as his charges, followed by Ron Bass in 1979.

This time around, King challenged Jerry Lawler for the Southern title.

“Sonny came out on the Saturday morning show and told the crowd the story of the knife attack and said he when he was on his deathbed he promised his son he was not going to die and he’d come back and fight for the title,” recalled Memphis historian Mark James. King faced Lawler in a rare babyface versus babyface match. “He asked for and got the shot, but Lawler got the win. They even shook hands after the match.”

King talked about how he ended up a manager, which wasn’t too long after Lawler’s manager Sam Bass had been killed in a car wreck, and Jimmy Hart was only in the early stages of his career. “We had some stuff going in Memphis, Tennessee, and it really weren’t clicking the way it needed to be; it was more off-balance one way or the other. When Jos Leduc and those guys came into Tennessee, then I talked to Jerry Jarrett. I sat down and had a conversation with him about doing some stuff. I thought it would click without a doubt,” King said about becoming a manager.

He had a very planned philosophy for managing at ringside.

“The managers, they used to really make me mad. I never controlled anything, but it used to aggravate me because the managers, I think, used to interfere with the matches. Wrestling fans are wrestling fans, and you can’t give them a whole lot of stuff. You have to give them something to identify with and keep it real simple. They understand that. But you’ve got the guys criss-crossing and you’re the manager, you grab the guy’s leg so you make your guy look weak. Now everybody’s mad, but they’re mad at the manager. The manager’s not going to draw you money, the guy that’s participating is going to draw you money. So instead of interfering with the match itself, I would object to stuff the ref is doing. You’d call him, ‘What are the rules here?’ But not to the point where I had his attention, but he’s not refereeing the match either. I don’t know. I think my success was letting everything be the way it was supposed to be and keeping it logical. That was it really.”

In the mid-’80s, King called it quits while working in Florida.

“I just got tired. There was so much aggravation,” he said. The aggravation included not being paid what he thought he deserved and not being listened to when he came up with ideas for programs and matches.

King insists he was in wrestling for the money, not for the recognition.

“I wanted the dollars. I didn’t give a shit about the recognition. My point was people coming into the arena. That was that. My idea all the time was what can we do different. We’ve got X amount of people here, good. Now let’s figure out, we’ve got these people tonight, regardless, let’s figure out how to bring more. My thing was never insult their intelligence.”

His outspokenness got him in trouble, he admits. “You know what happened was I got a bad name with promoters. It was always about money, it was always about money. And in reality, I knew of situations where there were two guys in a match, the white guy got X amount of dollars, the black guy got X amount of dollars … so now, when it came my turn, I wanted the dollars.”

He had enough confidence in his abilities that he didn’t demand up-front money.

“I would never ask for a guarantee. Guys would say, ‘Now you’re on top, ask them for a guarantee.’ I’d say, ‘No, that’s okay.’ And I’d talk to the promoter, and say, ‘Look, I’m not asking for a guarantee, but what I’m saying to you is, if I come in and I’m able to help you and your territory go up, I just ask you to pay me my money is all.’ A lot of time, it would go up, but you get excuses about how much money they’d lost before I came in. Who’s fault is that? It’s not my fault. It was more aggravation than it was worth, but I enjoyed it. I had a chance to save a couple of dollars. That’s all that matters.”

RELATED LINK