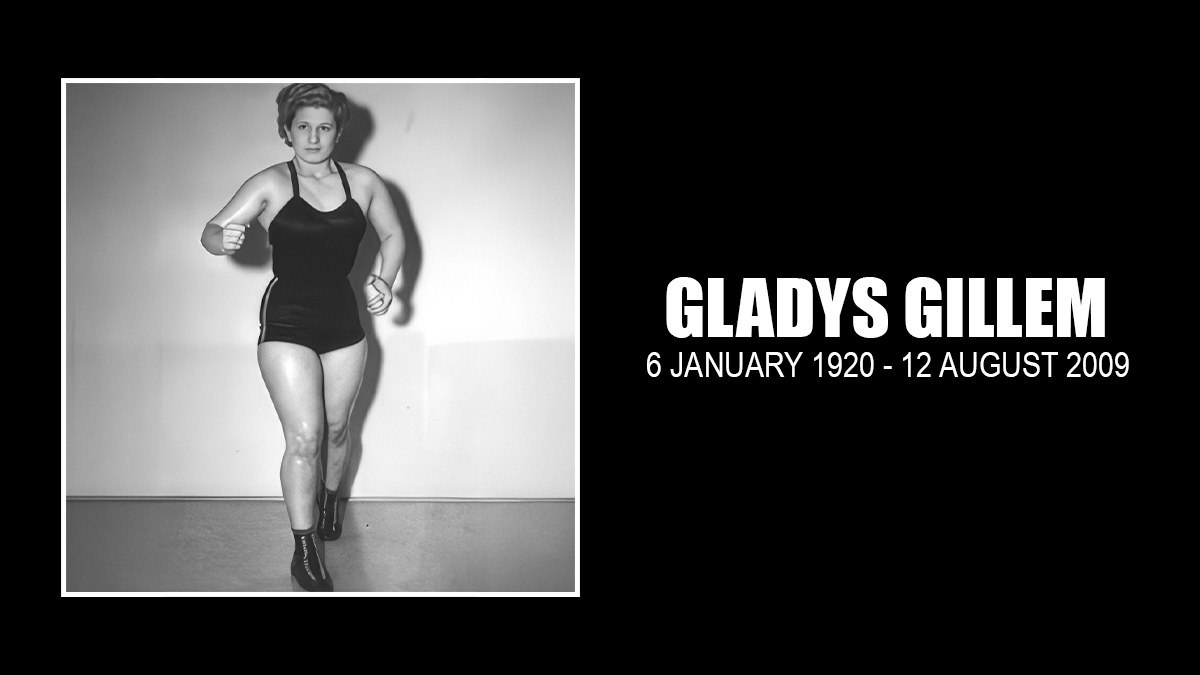

“After ten years in the wrestling business, I decided to try something easier, so I switched to lion taming.” Read that quote and try to resist learning more about the incredible life of Gladys “Killem” Gillem, which came to an end Wednesday at the age of 88.

Not only was Gillem a pioneering women’s wrestler, who paired against the champion Mildred Burke opened up the east coast of the United States for other women to follow, but she also tamed lions (one bit her), wrestled alligators (one bit her), ran a motel, and raised three children.

“We always knew mom was kind of different because she did whatever she wanted. You didn’t argue with her. She just wasn’t the normal every day mom,” said her daughter Claire McCoy.

Born January 6, 1920 in Birmingham, Alabama, to Fred and Clara Gillem, Gladys grew up a tomboy, fishing with her dad and hanging out with his buddies. She was in and out of a handful of schools, including getting the boot from Catholic school for putting minnows in the holy water, and tossed from high school for making homemade wine.

Athletically inclined, she toured for a softball team, winning the Alabama State title. Her father died when she was 19 and Gladys eventually had to take care of her invalid mother.

“My mother couldn’t walk and I carried her from the bed to the bathroom every day for a long time,” Gillem told journalist Jamie Melissa Hemmings in 2006. “I just got tired of it, giving her medicine, taking care of her like a nurse would.”

While acting as the homemaker, Gillem’s cooking skills improved immensely, and she would win 27 prizes for cooking — jams, preserves, cakes, cookies — at the Alabama State Fair. In later years, she would lament not following her culinary desires.

Instead, professional wrestling seemed like a way out.

“I got really tired of Birmingham. After awhile, I said, ‘There has to be more to life than this,'” Gillem told Scott Teal’s Whatever Happened To …? newsletter in January 1995. She went to a wrestling show in Fairfield, Alabama, and saw Mildred Burke in action, and approached promoter (and Burke’s husband) Billy Wolfe about getting in on the act.

“They didn’t have any other girls wrestling except this one girl that had left them,” Gillem told Hemmings. “They said, ‘We can’t take you, you are too fat.’ So I said, ‘You can put me on top of the car — I’m going to be a lady wrestler.'” Wolfe and Burke relented, and took Gillem to Tennessee. Quick schooling, and beatings, in the pro game followed,with Wilma Gordon being her primary teacher.

Soon, Gillem and Burke were paired, and stayed that way for a decade.

“Gladys ‘Kill ’em’ Gillem would turn out to be one of the most colorful and best-fitting ring monikers in the entire wrestling game,” wrote Jeff Leen in his biography of Burke, The Queen of the Ring: Sex, Muscles, Diamonds and the Making of an American Legend. “She was not beautiful and she was never allowed to win. But she was a terrific performer and she played a key role in Mildred Burke’s rise. With the addition of Gillem, Wolfe took a major step in the direction of building a stable of women wrestlers who could make Burke look good and at the same time draw fans of their own. This would be the linchpin of their success.”

Leen spent two days with Gillem in Pensacola, playing poker and buying lottery tickets with her and her son, Johnny. “Gladys ‘Killem’ Gillem was an American original whose place in pro wrestling history is assured,” Leen told SLAM! Wrestling. “An energetic daredevil in the ring, she was a bold and adventurous spirit who won over fans with her willingness to take things to the edge. Mildred Burke complained that Gillem bit her in the ring and had a ‘cauliflower head.’ But without Gladys Gillem to support her, there might not have been a Mildred Burke.”

Anyone who saw the 2004 documentary Lipstick & Dynamite, Piss & Vinegar: The First Ladies of Wrestling by director Ruth Leitman will recall Gillem stealing the movie with her colorful language and matter-of-fact talk of sleeping with Billy Wolfe to getting better bookings.

In her 2006 chat with Hemmings, Gillem was equally blunt, addressing her admissions about Wolfe in the film. She said she exposed Wolfe “for what he was. He was a lousy lay and he was a promoter. People take advantage of you.”

Gillem got tired of Wolfe’s tactics, which included taking 50 per cent of her pay for each match, as well as expenses, like the hotel rooms. According to Gillem, there were nights she made only two or three dollars.

So Killem Gillem up and left, heading back to Birmingham and taking it easy — but just for a little while.

She tried riding horses for show at the local horse track, but lacking the height and the quickness to get up on the horse, Gillem moved on briefly to being a trapeze artist.

Then the lion tamer, Capt. Ernest Enger, came along and Gillem went along for the ride. Besides the taming of the lions, Gillem also learned the art of procuring an old horse from a farmer, killing and skinning it to feed the lions for a week.

Though the initial runs at being a lion tamer resulted in maulings, Gillem picked things up quickly, and went from an understudy to part-owner then full-owner, working freelance for circuses, carnivals and private parties.

While working for the Bailey Bros. Circus, she met John Aloysious Wall, whom she married while touring north of Toronto. They would have three children: Kathleen Ann Wall, John Aloysious Wall Jr., Claire Fredrica Wall (McCoy). To say children grew up in interesting circumstances would be an understatement. Gillem would, for example, put the children to sleep on top of the lion cage while they were on the road.

After a circus trip to Central America went awry when Gillem caught malaria and the promoter ran off with the money, the family settled in Jacksonville, Florida, where Gillem took work wrestling alligators. (The secret, Gillem would say, was to turn the alligator over, and rub the soft spot on their bellies.)

“I remember living on Casper’s Alligator Farm down in Florida. That’s my first memory,” said McCoy. “My dad was there and they took care of the alligator farm. Me and my sister we would walk into the alligator pit and sit on the alligators’ backs so the tourists could take our pictures. We would put these huge snakes around our necks and they would take our pictures. It was our job to feed the animals and that kind of stuff. We had dogs that were from the circus, we did tricks with them and stuff. It’s weird but that’s what I remember.”

John Wall, working as a Broadway stagehand, was killed in New York, when a 500-pound box fell on his head. On her own again, Gillem went back on the road. In Calgary, her back gave out while wrestling an alligator and she got off the road, settling in Birmingham and running her mother’s boarding house until 1960.

In 1973, Gillem bought an old, run-down, 10-room motel, and named it the Birmingham Motel. There was a “lovers welcome” sign on the porch, and offered rooms for two hours for only $10.

Despite settling down, there were still the fair share of incidents, said her daughter, recalling one. “One day I was in there and she comes running in saying, ‘Get the car, get the car!’ I said why. She said, ‘Get the car and come with me,'” said McCoy, explaining that Gillem never learned to drive. “We go down the road and she said, ‘There she is!’ And mom jumps out of the car. And it’s this lady, she had this big bag; it turns out the lady had stolen the bedspread and the linen. She had rented a room and stolen it. The next thing I knew, they were going at each other and I get in the middle to stop them. I have a big hole in my ear from them pulling my earring out of my ear. I learned not to get in the middle ever again. To this date, she’ll knock the crap out of you or try her best if she gets upset. That’s the way she was. She didn’t mind standing up for herself. That’s one of the crazy memories I have. We really had to keep an eye on her.”

In 2003, Gillem had emergency bypass surgery, and her health continued to deteriorate in later years. Her children took care of her, just as she once looked after her mother.

In 2006, Gillem was reflective with Hemmings. “I’m sitting in a wheelchair talking to you and thank God I’m breathing, that’s the way I look at it. At my age, there are a lot of people who made a lot of money, but they are dead right now. My hobby is raising plants now.”

Her life was indeed one of taking the bumps — and not just in the ring when she was the heel.

“I use her as an example for my kids, you just don’t quit. You keep going to survive and don’t let people get you down,” said McCoy. “Whatever happened, my mother would pick herself up and keep going. A lot of women should take a lesson from her. She didn’t need a man, she could take care of herself. My mother taught me that women are capable and they don’t have to rely on anybody. You have to take care of yourself. That’s the life she lived. She never waited for people to hand something to her.”

Gillem had the scars to prove that it wasn’t an easy road.

“I’ve learned the hard way about life,” said Gillem. When you’ve lived as long as I have you will learn about life. You haven’t had the hard knocks that I’ve had.”