Back in the ’80s when squashes were the norm on TV, people used to joke about matches pitting guys like The Amazing Ultra-Strong Mega-Destroyer Superstar against some generic guy named Fred. One of the most recognized “Fred’s” from that era is Dusty Wolfe, who recently sat down with SLAM! Wrestling in San Antonio to discuss his career in, and his views on, the wrestling industry.

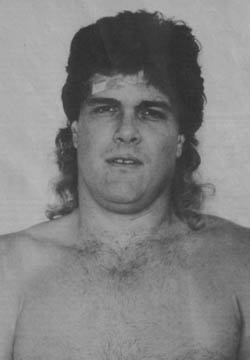

Dusty Wolfe. All photos courtesy Juanita Timbs

Thanks to his regular appearances on WWF television back in the ’80s and ’90s, Wolfe is one of the most memorable low-card performers of that era, along with others like Steve Lombardi, S.D. Jones, Mike Sharpe, Rick McGraw, and AJ Petruzzi. One may naively think that his status as enhancement talent, or ‘jobber’ means that Wolfe didn’t have a lot of in-ring experience — but one would be wrong.

“I started training when I was 18,” he recalled. “When I was in high school, I told myself I had three options: I could play football, I could play baseball, or I could go into wrestling. After playing football, it became obvious that I wasn’t going to be doing that. I had a chance to play baseball, but I got sick — I had to literally learn how to walk all over again — so that killed my chances. I took a job to help my mom pay some of the medical bills, and when I was 18, I started training with Ken Johnson — the man who broke Shawn Michaels into the business, and had the school with Shawn years later — down here in Southwest Championship Wrestling.”

His training regimen was markedly old-school, and much different than how today’s wrestlers learn the craft.

“Back then, there were no schools. You had someone (in the company) who would take you and train you, but the office would have to say it was okay (first), and that would only be if you stood any chance of ever making money. Basically,” he explained, “they’d just beat the hell out of you. If you stuck around, then they’d start showing you something. They made getting into the ring a privilege. At schools today, you get in the ring and you’re running the ropes on the first day. Back then, you’d spend the first five, six months taking bumps on the floor, and exercising until you were completely blown up. Getting in the ring and getting stretched was a privilege.”

While that sounds like a tough road to slough, Wolfe acknowledges that he still had it easier than some of the others who were there at around the same time.

“Ken didn’t beat me up too bad, we were buddies. I felt bad for some of the guys. There were some that got beat up so bad that they had to call someone just to come pick them up and get them out of the building.”

The rough lessons learned, Dusty then took his skills on the road, wrestling in a number of territories for the next few years.

“I was in San Antonio for about a year and a half. For the first six months or so, I was only wrestling once a week or once every other week. I realized then that local boys, if they stay local and never leave, they can’t make money. I called every place that was still open in ’83, and in January ’84, I went to Kansas City, being booked under Ken Robley. Then from there, I went to Memphis, Florida, and then World Class, Southwest Texas, and Puerto Rico and Hawaii. I hit most of the big territories except Portland and Pensacola, Charlotte, and for (Verne) Gagne (in Minnesota).”

During this time, Wolfe was near the top of the card in most of the territories where he worked.

“I can’t say I was in the main event,” he conceded. “I was generally the underdog babyface, ready to be groomed. Then every time I was just ready, the booker would get fired, and then I’d be the first or second guy out the door with him. Like every booker, he had a crew, and when the booker goes, his crew has to go to. I got near the main event.”

In 1987, Wolfe headed to the WWE (then WWF), where the main events would be more distant than ever. Wolfe spent most of his time as enhancement talent — or, in other words, as a TV jobber. Though it wasn’t necessarily the most glamourous role, Wolfe had other considerations in making the decision.

“With what they were offering me, I would make in one night what I had been making in a week (in the territories), so I didn’t care. I wasn’t overly concerned with being in the main event. I didn’t have that ego. I could see the bodies of the guys they were making into stars, and I knew that wouldn’t be me. But I could see the writing on the wall as far as the territories would go, knew there wasn’t money to be made there, and I decided to sign.”

While in WWE, Wolfe was used primarily as enhancement talent on the company’s weekly television shows. Unlike RAW or Smackdown today, TV in that era generally featured squash matches, with big name matches saved for house shows and pay-per-views. Wolfe was a staple feature of TV, losing to some of the biggest names of the business in matches that were ancillary to any big feuds.

“They would (tape) three weeks worth of shows in one night, and they would do that two nights in a row,” he recalled. “If you caught two matches on the first night, that meant you were on TV for two of the next three weeks. Even if you only got one match the second night, that means you were on three weeks out of six. I was on TV more than the stars, unless they were in a big hot angle.”

A young Dusty Wolfe

Despite losing most, if not every one of his matches, Wolfe prided himself on his performances. He notes that many of the top names wanted to work with him, as he was able to sell a squash beating but still make the match entertaining for the viewer. The fact that he lost doesn’t really bother him, though that wasn’t always the case.

“I used to get bothered by being called ‘jobber’. But I don’t care anymore. I realized that people that use it are doing so to make themselves feel better, make them feel that they’re more important than you are, that they’re superior. Sure, I didn’t make great money, but considering where I was in my life at that time, they took care of me better than maybe they even should have.”

In addition to wrestling, Wolfe was often tasked with other duties, including ‘babysitting’ the actor Tiny Lister, better known to wrestling fans as Zeus, Hulk Hogan’s co-star from No Holds Barred who was brought into the company for a brief spell.

“It was fun,” Wolfe remembered, “and it was a good deal for me. It was all expenses paid to travel with him, plus I would also get to work (in the ring), so I would also get my payday for that. I had him from about April through December — around eight, nine months. He was a good guy, and smart. He was very bright, he just didn’t always know how the boys worked. I told him two things: one, to stay away from Davey Boy (Smith) and Dynamite Kid; and two, I let him know that the rest of them were (likely) going to give him some grief, because there was resentment that he came down there and was making big money, but he hadn’t done anything. He was offered a full-time job, but didn’t take it, otherwise, I would have traveled with him some more.”

On the way into the ring

Wolfe toiled for a few years in WWE before giving his notice after a particularly unrewarding tour.

“The money had gone south. It was right at the time the steroids scandals had busted loose. I had made a three-day run into Canada, and after my draws, taxes, and the exchange, I owed the office money — around fifty bucks. I opened the mail and there was an IOU. So I quit.”

Besides, Wolfe figured his time with the company wouldn’t have lasted much longer anyway, having survived two roster cuts earlier that year. The day he quit, he got a call from Kendo Nagasaki with an offer to work in Japan, and headed overseas.

“I (went to) Japan three times over the next couple of years. I traveled to Puerto Rico and South Africa. Then I worked the independents in 1994 through 1996. Back then, the independents were a lot more like the territories than they are now — they had their own TV, did a few shows at a time. Then I went to WCW and stayed there until 1998.”

Working in WCW had its positives and negatives, but overall, Wolfe found it to be rewarding, at least financially.

“I probably didn’t work ten times during the time I was there. They were literally giving money away. Just show up, sign in, and they’d tell you, ‘You’re not on the card tonight.’ That was not a bad deal at all.”

That said, there were things that he found frustrating about the time. In particular, WCW’s strategy of putting main event matches on free TV (during the Monday Night Wars).

“That was just (then WCW head Eric) Bischoff being ignorant,” he stated bluntly. “(He didn’t realize that) you could do competitive matches and still have some guys who were the job guys. Bischoff didn’t have the sense to do that. He pushed the envelope, so Vince (McMahon) had to follow. It made for some interesting TV, but it set the bar so high, that eventually it got to the level that they couldn’t follow themselves.”

“Don’t get me wrong. The business was due for a change, it had to change … you couldn’t fill primetime with squash matches. But you give away so many quality matches every (week), why would you expect people to come out and pay for it? It helped kill that company. Bischoff was great at putting a two-hour TV show together; he could put some good stuff together to keep your attention for those two hours. But there was nothing there to draw you into the buildings, and especially nothing there to draw you to order the pay-per-views.”

No longer a required commodity for the national companies, Wolfe headed back to the independent scene, where he has been ever since. Now he works a few places regularly in Texas and Louisiana, with the occasional trip overseas to Europe. It’s on the indy scene that Wolfe predicts he will have his last match, possibly even as early as next year.

“I got a little burned out at the end of last year. I can see myself getting out it, probably in another year or two. I’m going back to college to get my degree, and go in that direction. I’ve spent 25 years in the business — that’s enough. I’ll work for someone if they call me, and if it’s someone who I like and who I trust. But other than that, once I get this degree, then I’m done. There’s nothing left, there’s nowhere to go. I’m ready to move on.”

Those comments shouldn’t be construed as Wolfe regretting his career; on the contrary, he says. He has plenty of great memories from his life in the squared circle.

“Favourite memories … the first night I wrestled against the Rock ‘n’ Roll Express. I didn’t realize how over they were until they came through the crowd, and that crowd hit 150 decibels. That was the loudest crowd reaction I’ve ever heard, including some of the Hulkamania reactions. The building being set on fire in Singapore. A riot in Cape Town, South Africa that I thought I would be killed in.”

Still other of his favourite memories involve the many legendary buildings where he was lucky enough to appear.

“I remember my first match in Madison Square Garden. The mark was out of me by then, but there’s still something about the Garden. That was the baby of professional wrestling, that was the marquee place. That was the last time I’ve been scared. I was as nervous as hell. I’ve seen the tape, and you can tell that I was scared for about the first two minutes. I had to tell myself it was just another arena, or else I was going to (crap) myself in front of the crowd in the most famous arena in the country. I ended up having a decent match.”

“I was talking with Bill Apter and he said that I was probably the only non-main-event guy that wrestled in every building that meant something. The first time I worked the Sportatorium — it was great until I walked in and saw what a dump it was … it wouldn’t even make code. Still, that building had a mystique to it. Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto had a mystique to it, too. The Kiel Center in St. Louis. I’m old enough to understand the mystique that some of those buildings had. Arena Mexico — it’s a dump, they should burn it — but it has that mystique. Burning it is probably too good for it, it’s disgusting, horrible … they should bulldoze it. But it’s got the mystique. I never made the Egg Dome, but I made Korakuen Hall, which was right next door. Those are my mark-out moments, the fact that I actually got to be there, that I was good enough or that somebody thought enough of me that I made it there.”

Dusty with daughter Codee

Of course, no business is perfect, and in running down his career, Wolfe can easily think of some of the more unpleasant realities of life in the industry.”

“Even more than the injuries, missing your kids grow up, that’s the worst. Nothing tops that — I’m lucky they still love me.”

“As far as the business itself, (one unpleasant memory was) being arrested in South Africa and not knowing if I’d ever get home. I got sued over a promoter’s losses, and the losses he sued us over were the wages he never paid us! I’m arrested on all these charges, and they took my passport, and I wasn’t sure if I’d get home. That was bad. Another was (the time I got) arrested in Mexico City. I got arrested one night for nothing. I was a white boy, so I stood out like a sore thumb. I was trying to visit a friend of mine, and as I’m crossing the street to get to his house, I get stopped by the police. Next thing you know, I am stripped naked in this intersection, and they’re strip-searching me, then they handcuff me. It cost me 200 dollars to get out of the back of that car. I will never go back to Mexico City again, I hate that city. You couldn’t pay me enough to go back there.”

Arrests notwithstanding, Wolfe is overall pretty satisfied with his life in the mat wars. And, even though he is contemplating retirement from in-ring participation, he wouldn’t rule out an office job some day, if given the opportunity.

“If Vince called me tomorrow and told me he had a job for me, I’d go back. I wouldn’t be in the ring, I don’t fit. But something in the office, I’d go back. I don’t think that’s ever going to happen, though, and I accept that. But, you know what? This business has been good to me. It took me all over the world. I got paid to do things that some people save their whole lives to do, and I was doing it before I was thirty. I wouldn’t have my kids if I wasn’t in the business. I have three great kids. I’ve made lots of good friends. I truly have been blessed.”

RELATED LINK