This used to be a pretty exciting time of year for J.J. Dillon. In the almost eight years that he spent in the WWE front office, he knew that the advent of spring meant the return of WrestleMania, the grandest spectacle of entertainment and excess in the sport.

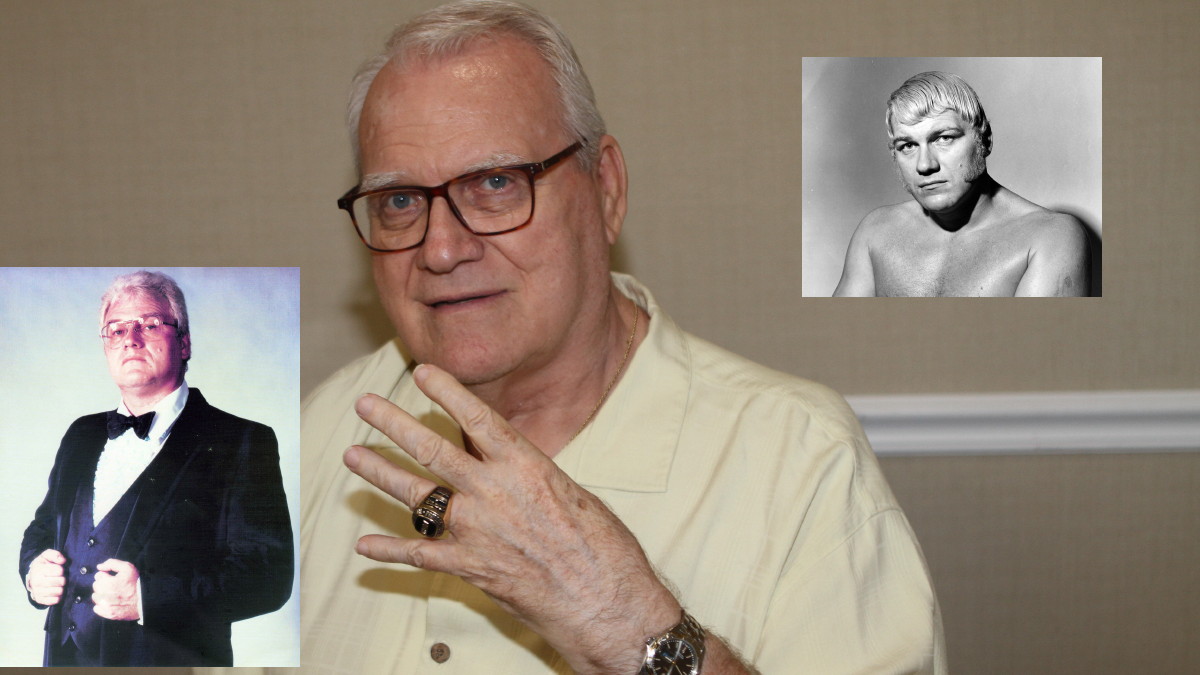

But now, that’s a bygone thrill for Dillon, a major figure in the business as a wrestler, manager and executive for more than a quarter-century. As he watches the evolution of pro wrestling from his home in Delaware, he’s afraid the thrill eventually will be gone for others, as well.

“I think there will always be a WrestleMania because it’s like the Super Bowl,” he mused in a conversation with SLAM! Wrestling. “People who don’t watch all year will get wrapped up in that because it’s an annual thing with celebrities and every year they come up with something new — Donald Trump or whatever it happens to be.”

But even as WrestleMania continues on an unabated money-making roll, Dillon suspects the emotional bond that moves fans and motivates star-struck youngsters to dedicate themselves to the sport is eroding beyond repair.

“The modern wrestlers … they have that deer in the headlight look. They have to sit down and script a match, and it’s a series of high-impact moves with no rhyme or reason and it’s devoid of emotion, It’s gone and they don’t really understand how that’s the foundation of what wrestling should be — that emotion,” he said. “The people who do understand it are becoming so far and few between. It’s a dying art.”

Dillon, born James A. Morrison in New Jersey nearly 65 years ago, speaks matter-of-factly, unlike the irritating prattler he was as a singles and tag champ in the 1970s or manager of the famed Four Horsemen in the 1980s. He’s comfortably slid into the role of a professor emeritus with a lifelong education in wrestling and will stand before his colleagues to be honored at the Cauliflower Alley Club reunion in Las Vegas later this month. So his observations are sincere, even if he oozed insincerity as a heel in arenas from the Carolinas and Texas to the Maritimes.

“It’s easy to be critical about the current product. I feel I can be objective about it. I don’t have any hidden agenda. I don’t have any axe to grind,” he said. “I’m out of the business. It’s not like, ‘Gee, I’ve got to be careful what I say about Vince McMahon because I may get a call one day and I might be able to get some work for a year.’ That’s not it.”

In fact, Dillon is downcast only because he fears tomorrow’s grapplers never will experience the same emotional sweetness he tasted when he discovered wrestling on TV as a teenager in the 1950s.

“I always believed that people were fans of wrestling that maybe didn’t necessarily believe it was real, but it’s like sometimes you want to believe,” he stressed. “And if they came to an event and the work level was good because you had quality talent, sometimes it could look so real that it became real. It was the temporary suspension of disbelief, as one comment accurately describes how it was. That was when I think wrestling was at its very best.”

With the demise of the territorial system in favor of essentially one national company, the WWE, young wrestlers seldom get a chance to work out the kinks in their styles and personalities, Dillon said. That means the quality of in-ring action has been on the wane — and with it, the emotional tie between fans and the sport.

“Guys who are working for these little independent shows are working two or three times a month,” he noted. “I only grew, and grew over time, when I was working every night of the week against different guys in different towns with different styles. You did TV, you did interviews, you did angles and then you went to another territory and did it again. The toughest part was to come in a new territory and draw attention to you because of something about your or your personality or your style, or whatever. All of that is gone.”

In fact, as he posited in his 2005 autobiography, Wrestlers Are Like Seagulls: From McMahon to McMahon, he sees WrestleMania and wrestling generally becoming less important in the scheme of things — “a novelty attraction that people go see periodically but not follow because the emotion and the depth of the characters is not there.”

Dillon was a passionate fan of Vincent J. McMahon’s Northeast promotion from the start, serving as Johnny Valentine’s fan club president before breaking into the business as a referee for about six years. He had a couple of matches in the early 1960s, but, following advice given to him by The Zebra Kid (George Bollas), got a college education as the foundation for his professional life.

Hence, James Morrison, Albright College, class of 1964, majored in sociology, minored in history, was a member of the Kappa Upsilon Phi fraternity and a the college wrestling team. A few years later, Morrison because Dillon — the moniker probably owes a debt to a character in the popular ’60s TV western Gunsmoke — and considers his first real match to be a tag bout in The Sheik’s Detroit-area promotion in 1968.

His first full-time territory was in the Carolinas in 1971 at the age of 29, rather advanced for a wrestler. A couple of years later, he headed to the Maritimes for the summer circuit as an undersized heel against Archie “The Mongolian Stomper” Gouldie, a fan favorite at the time. “I said, ‘Have you ever thought about changing the formula, and not going with — obviously, I wasn’t the big, physical guy — and go with a wrestling heel that had a big mouth, and just reverse the process?” he recalled asking local promoters. “They finally liked the idea, and decided to go with it.”

That began an association with Gouldie that later morphed into a managerial gig in Texas. Dillon starred in Florida and the Central States territory with a variety of titles, but fans of more recent vintage known him more for his work as a front man. In the 1980s, he was the brains behind the unholy alliance of Ric Flair, Tully Blanchard, and Arn and Ole Anderson, wrestling’s Four Horseman. His work there came to an end after TV mogul Ted Turner bought Jim Crockett Promotions and formed Atlanta-based World Championship Wrestling.

“I very quickly realized it wasn’t the wonderful situation that everyone thought it would be,” Dillon laughed. After a phone call from the then-WWF, he headed back to the Northeast for Vincent K. McMahon. “I thought, ‘Wow, it’s come full circle for me. I’m back now with the big show, as big as it gets and now Vince’s son has recruited me.’ I spent almost eight years there. It was a wonderful learning experience, good and bad, but I did learn a lot. I had a wonderful career. I saw all the changes and from the inside, too.”

Dillon has been working for the Delaware corrections agency in recent years, but the sport still tugs at his heart, as he found when he attended his first Cauliflower Alley Club reunion last year after years of missing out on the annual event.

There, motoring down the hallway of the Plaza Hotel and Casino, was a cantankerous symbol of wrestling’s past, a star that Dillon admired as a fan in New Jersey and briefly knew as a fellow wrestler in Texas years later.

“We were sitting in the hotel and I saw a guy in a wheelchair and said to somebody, ‘Gee, the guy looks familiar.’ ‘That’s Bob Orton (Sr.).’ And I jumped up and I went over and I was so happy to see him,” Dillon said.

“[His daughter] Rhonda was there and I hadn’t seen her in all those years. Sadly, it was a matter of weeks that he passed away. I just felt so good that I did go when I did and had a chance to see him again after almost 50 years.”

2007 CAC HONOREES

Iron Mike Award – Don Leo Jonathan

Lou Thesz Award – Danny Hodge

Lifetime Achievement Award – Bob Geigel

Posthumous Award – Yukon Eric, Betty Jo Hawkins

Other Honorees – J.J. Dillon, Rock Riddle, Tito Carreon, Duke Myers, Bob Leonard, Laura Martinez, Bob Kelly

RELATED LINKS