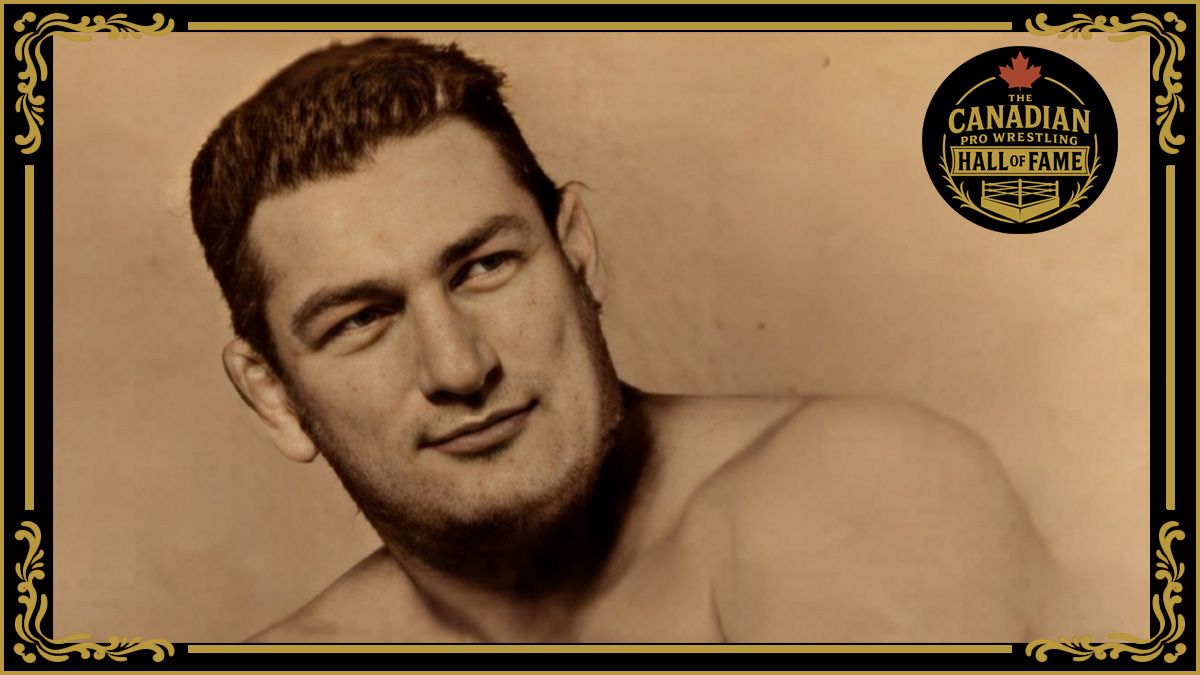

The wrestling story of Hamilton’s Jim ‘Dano’ McDonald, who died on March 4, 2004 at age 81 in Eatonville, Washington, cannot be told without talking about World War II, and the people like him who were denied enlistment because of their key jobs.

For the young, eager and athletic McDonald, it was his job as an operator on the roller mill at Stelco that was deemed essential to the war effort.

“I was froze on the job because I was an operator down there on the roller mill,” McDonald told this author back in January 2002. “While I was wrestling, I was working at the steel mill. They wouldn’t draft me. Even when I went down and tried to get in to the Argyle Southern Highlanders, I took my physical and everything, and I passed everything, except when the time come, they called me up in the office in the steel mill and said, ‘Hey, listen, we don’t keep you here in this steel mill because we like you, or any other reason. We need you.’ Because operators, it was hard to find people that could operate those big hotbeds and steels. Gosh, I took to that like a monkey to a fig. And it was easy for me, but I hated it. Shift work, and I didn’t want to work in a damn factory. Couldn’t wait until the war was over. As soon as it was, I quit.”

One of his co-workers at Stelco was Frank ‘Scotty’ Thompson, who became his training partner for wrestling. Both fans of amateur wrestling, they used to work out after their 7-to-3 pm shift ended at Hamilton’s Municipal Swimming pool, where the pros put on their exhibitions on the ring, set up on planks above the pool.

“We would meet at the pool and work out for an hour or so before the matches. These were the day when the light heavies would be on one week and the following week the heavyweights would come in,” Thompson said.

Herb Larsen was the key man who got them both into the pro mat game. “He’s the one that more or less started me in professional wrestling,” said McDonald. He turned pro at 18, and got married too, to Phyllis, whom he stayed with until her death in 2003.

“I liked wrestling. I thought it would be a nice profession,” he said, adding that the training was pretty tough. “They really worked at being wrestlers. … I think the first cauliflower ear I had, I couldn’t have been more than 20 years old.” His dad was particularly supportive of his efforts to become a pro wrestler.

Joe Maich, the promoter for southern Ontario, gave him the first name that most fans know him under. “He didn’t like the name Jimmy McDonald, so he said, ‘Hey, we’re going to name you after that old great Irish wrestler Danno McDonald.’ It sounded better than Jim, so I left it that way.”

While the War was on, McDonald worked close by the Steel City. “You couldn’t go very far. The furthest I’d go would be Detroit or Chicago once in a while, but I’d have to go on the train because you didn’t have enough gas to go around.”

When the War ended, he quit his job at Stelco and hit the road. “Being as small as I was, I was probably only about 160 some pounds, and there wasn’t very many places where you could get booked. In Mexico, they’re all small people. That’s the first place I went to, was down in Mexico, Mexico City,” he said. “They were a bunch of jitterbugs down there. It was pretty tough. Mexico City, 7,000-8,000 feet above sea level, and it takes you quite a little while to get acclimated in that kind of an elevation.”

Dano worked the smaller body territories, like El Paso, Texas for Don Hill, then beefed up for the big time in Chicago. “I got a little bigger and they could start booking me with the bigger guys — Rudy Kay, Billy Geltz,” he said. “Rudy Kay, he was a big bellied guy. Boy, I tell you, he used to take some hell of them bumps. Him and Schnabel, Hans Schnabel, they used to have the darnedest matches. One time in Chicago they bodyslammed each other so many times they broke the damn ring down!”

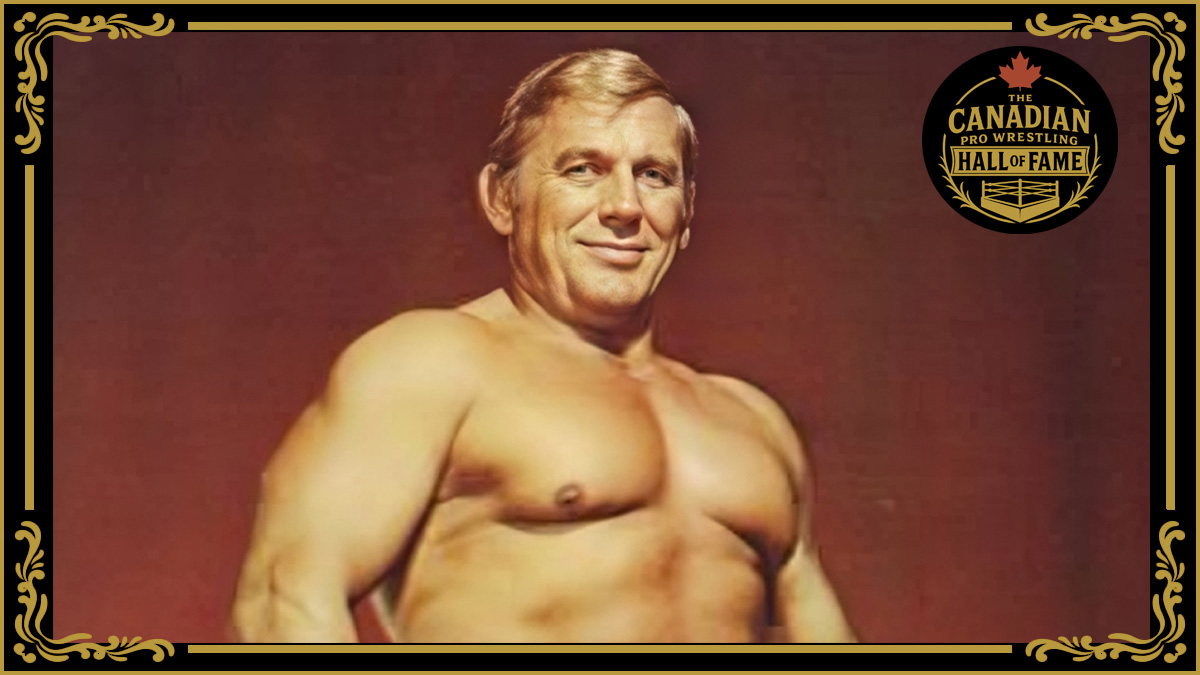

Other territories he worked included Albuquerque, New Mexico, Idaho, Utah, Texas, Calgary, Edmonton, Vancouver, Portland and Seattle. “I really enjoyed being with the wrestlers and wrestling. I was Rocky Mountain heavyweight champion for a total of five years,” he said.

Eventually, he settled in Portland, and to this day, his wrestling career is most associated with his time in the Pacific Northwest.

“Not many ‘current’ fans may know much about him, but he had more matches in the Northwest area than any other wrestler in the history of the business,” recalled former Seattle promoter Dean Silverstone. “From about 1954 until 1968, there was never a night someplace in the Pacific Northwest (including B.C.) where he was not on the card.”

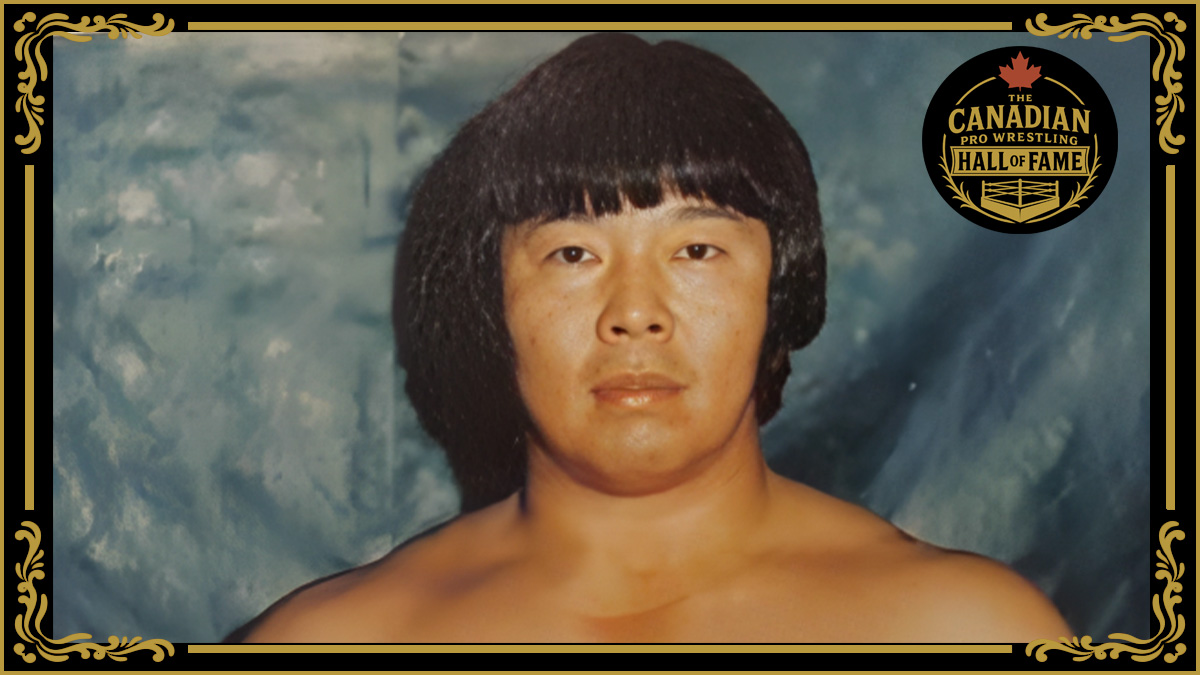

In a 1995 interview, Dano stated “I worked against Ivan Kameroff, Kurt von Poppenheim, and Soldat Gorky, more times than the New York Yankees played the Detroit Tigers.” He also wrestled the likes of Frank Stojack, Burt Ruby and Earl McCready.

Born James Gregory McDonald on February 18, 1923 in North Sydney, Nova Scotia, his family moved to Hamilton when he was four, and his father worked for Stelco. McDonald wasn’t a big kid. “For a longtime, I was kind of a skinny-weight, and I had a heckofa job getting over 200. I got up to around 220, and got up as far as 230,” he recalled. He grew to 5-foot-11.

Dano and Phyllis had two daughters, Shirley and Donna, and lived in Eatonville, Washington for many years. Dano quit wrestling in the 1960s to become a full-time mortician and kept at that until retiring.

Yet, his love for the wrestling business remained. In 1974, Silverstone brought Dano McDonald out of retirement for a series of matches in Seattle. His initial return angle was against Chris Colt, who had vowed on TV that “grandpa Dano” couldn’t last five minutes with him.

“He had half a dozen or so matches in ’74 for me, before he said the next one would be his last, because he and wife Phyllis, who he married in 1941, were planning on driving to Reno. So I booked him one more time in Seattle, and I watched the match knowing it would be his last. As usual, it was great,” Silverstone recalled in a Whatever Happened To … column. “Five years later, I learned that Dano broke three ribs in that match when his opponent stomped on his stomach. I heard it not from Dano, but from another source, and when I phoned Dano to yell at him, he simply shrugged it off as if it were all part of some big game plan. These athletes taught me when to speak up and when to keep quiet and I don’t know of any people I admire more.”