|

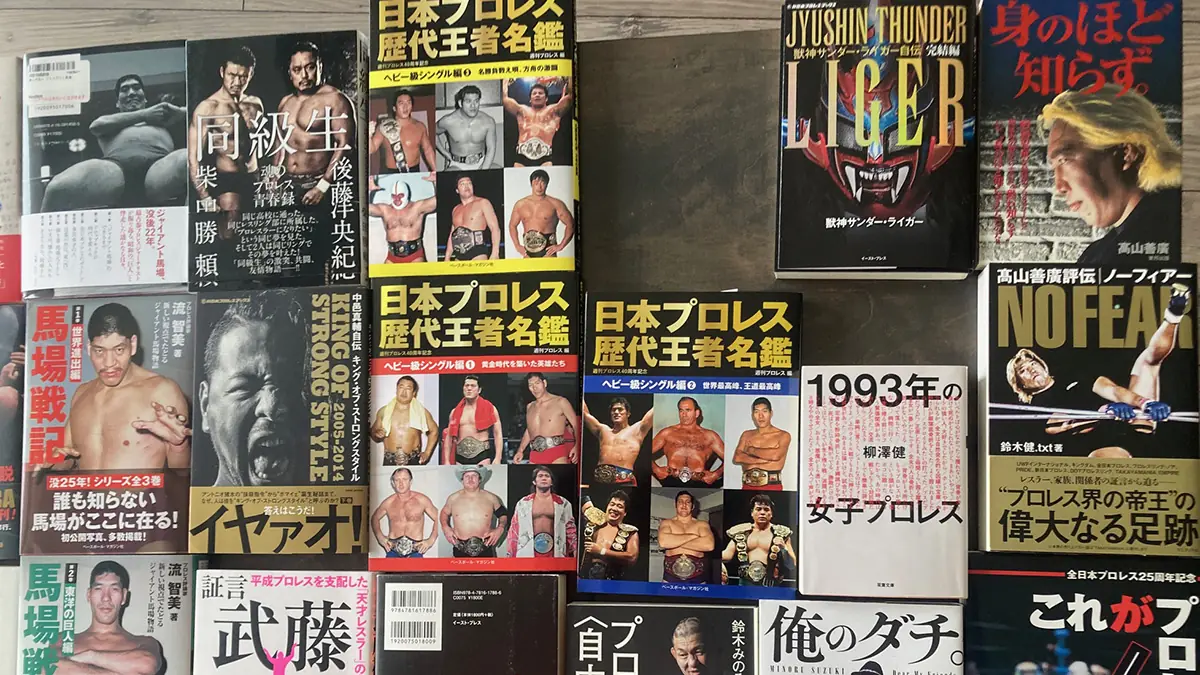

| Ultimo Dragon in WCW. |

A brilliant career came to an end last Thursday as Yoshihiro Asai, better known as Ultimo Dragon, held a press conference in Japan, quietly announcing his retirement from pro wrestling.

At the press conference, Asai contended that WCW fired him in July of 1998 after a company-hired physician cut several nerves in his arm, rendering the limb virtually useless.

How ironic that after years of absorbing punishing blows and sticking to a taxing travel schedule, it may have been an errant stroke of a surgeon’s scalpel that sidelined him for good.

It seems almost appropriate that the announcement came with little fanfare or notice. During the course of his 12-year career, Asai carried himself with a quiet, reserved dignity. Despite being one of the most decorated junior heavyweight wrestlers in history, Asai never called much attention to himself.

In an industry comprised of braggarts, Asai distinguished himself with his modesty.

But Asai’s demenaour was the only thing modest about him. He was a wrestler of considerable skill, regarded by many hardcore fans as, pound for pound, one of the best wrestlers of the 1990s.

Asai was a renaissance wrestler, jetting around the world and maintaining simultaneous wrestling schedules in Japan, Mexico and the U.S. His work ethic inside the ring was unparalleled, his thirst to put on a great match insatiable.

These were just some of the characteristics that made Asai so special.

Few, if any wrestlers, took as much pride in the quality of their work and the practice of their art than Asai. Few, if any, were as graceful inside the ring.

He created a ‘wrestling potpourri’ of sorts by combining the ballet-like movement of Lucha Libre with the lightning quick pace of Puroresu into his working style. He amalgamated the two culturally rich and diverse wrestling cultures into the single, most efficient and effective working style in the business.

Noted for his lethal, stiff kicks to his opponent’s sternum, Asai was an innovator in the sport, creating and popularizing such moves as the quebrada (the Lionsault) and the Asai moonsault (a move named after him).

Trained in the famous New Japan Pro Wrestling Dojo, company officials did not offer him a contract upon completion of his training. They said he was too small and would never make it in wrestling. Undaunted, Asai made his way to Mexico where he quickly established himself on the International scene.

Asai started in the old Universal Wrestling Association before moving to the EMLL promotion in October of 1991 where he was given the name Ultimo Dragon (translated into English as the last student of “The Dragon” Bruce Lee) by booker Antonio Pena.

While in Mexico, he had memorable matches with Mexican legends Negro Casas, El Felino and a certain Canadian wrestler by the name of Chris Jericho.

Billed as Corazon de Leon (Lion Heart) Jericho and Dragon set EMLL on fire with their matches, battling over the NWA World Middleweight title. Their feud set a new standard of excellence by foreign wrestlers in the work-ethic crazed Mexico promotion, earning both of them a place in Lucha Libre lore.

The two took their feud overseas where they continued their epic battles in Japan’s WAR promotion. On July 7, 1995 the two put on one of the best matches of that year, tearing down the house before a sold out crowd at Tokyo’s venerable Sumo Hall.

Speaking about this match, Jericho wrote on his website last week, “this is one of my top two or three best EVER. We had tremendous chemistry and that shows in this match. We got a standing ovation from the boys in the dressing room when we returned.”

Having competed in Mexico and Japan, Jericho worked with top junior heavyweight workers such as Jushin ‘Thunder’ Liger, The Great Sasuke, Shinjiro Otani, Koji Kanemoto, Negro Casas and Chris Benoit. Out of all these formidable wrestlers, he considers Dragon as one of his best opponents.

“I worked with Dragon for about a year straight. Asai is probably my favorite opponent that I ever worked with.”

Asai split his time in Japan between WAR and New Japan, capturing the IWGP Junior Heavyweight title twice, cementing his stature as one of the top junior heavyweight’s in history and making New Japan regret their decision 10 years earlier.

Dragon entered WCW in mid-1996 and had outstanding matches with Rey Misterio Jr., Eddie Guerrero, Dean Malenko and Chris Benoit the rest of the year, before capturing the WCW Cruiserweight title in December.

On August 2, 1996 Dragon competed in the J-Crown title tournament, an event that brought eight of the top junior heavyweight champions together for the purpose of unifying the titles. As WAR’s International Junior Heavyweight, Dragon was booked in the finals where he lost to Michinoku Pro star the Great Sasuke.

Dragon won the J-Crown two months later in Osaka, Japan. By virtue of his victory Dragon became the only man in wrestling history to hold 10 titles simultaneously (he held the WCW Cruiserweight title and the NWA middleweight at the time).

In 1998, aside from his full-time wrestling schedule, Asai formed Grupo Revolucion, his own promotion based out of Naucalpan, Mexico. Bound by a sense of obligation to pass on the knowledge he had gained to the next generation, Asai trained several of the top young wrestlers in Mexico. Like he had did a decade earlier, several young Japanese wrestlers fled Japan for Mexico for the chance to study under Asai.

Grupo Revolucion became a vehicle promotion where his trainees began to cut their teeth and gain invaluable experience. Unlike other older wrestlers, Asai felt compelled to help out the younger generation of wrestlers getting their start in the business. He selflessly gave his students his time and attention, bound by a responsibility to help ensure the future growth of pro wrestling.

And now in retirement, he’s as committed to that cause as ever. Toryumon, a promotion that Asai started last year in Japan, is a facsimile of his Mexican promotion, providing training and work experience. Toryumon and Grupo Revolucion have been involved in a talent exchange and have working agreements with several Japanese and Mexican promotions, making them the leading hotbeds of wrestling featuring young and up and coming talent.

Aside from a small handful of wrestling sites and a classy mention by Jeff Marek of Live Audio Wrestling, Dragon’s retirement went without much notice by wrestling media and fans in North America.

It’s unfortunate that Asai’s retirement barely registered with reporters and fans over here. The level of indifference they displayed is nothing short of criminal. It is also symptomatic of the xenophobic attitude North American fans seem to have towards international wrestlers and foreign wrestling cultures.

That aside, we should never lose sight of the fact of how special Ultimo Dragon was.

Wrestler. Promoter. Trainer. Ambassador for the sport. His is a legacy that will never be duplicated.