Dave Cameron knew wrestlers better than wrestlers knew themselves. Case in point: Jack Claybourne, the high flyer and first Black wrestler to appear in New Zealand, was autographing a photograph for the teenaged Cameron in the late 1940s. “My memories of Jack, he was signing a picture for me and I had to prompt him on spelling Claybourne. He got halfway through and asked me the next letter,” Cameron laughed.

Little things and big things. From fixing Claybourne’s spelling to mingling with the legendary George Hackenschmidt in London. From wrestling a few bouts as an undersized grappler to introducing André the Giant to North American wrestling magazines. With more than a quarter-century as a fan, accumulator, researcher and author, the breadth of David Ian Cameron’s knowledge of boxing and wrestling was staggering.

“I started sending stuff around the world in the late 1940s,” said Cameron, a member of the New Zealand Boxing Hall of Fame. “I think the first bit published was in an English wrestling magazine called ‘Mat.’ I used to send boxing news from New Zealand to the American ring magazine also, when they covered the whole world. I guess I just loved writing bits and publicising my favourite sports.”

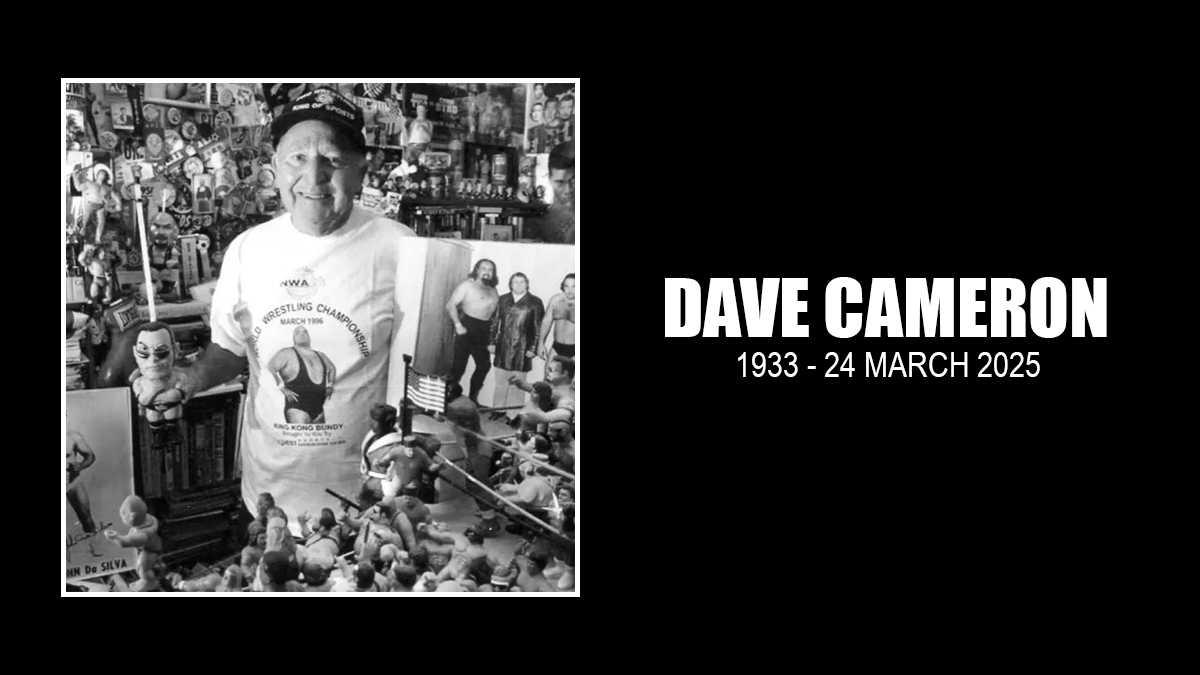

Cameron, 91, died at an assisted living facility in Auckland on March 24. He had been in declining health though he continued to contribute to boxing and wrestling projects well into his 80s. While his death marks the final break of the first generation of the great wrestling researchers, his legacy lives on at the New Zealand library in Auckland, which holds his collection of nearly 500 albums and scrapbooks spanning wrestling history from 1880 to 2017.

“Dave and I traded wrestling memorabilia for many years,” said historian and collector Dr. Bob Bryla. “We would provide each other with items that may not have been easily available to us in our respective countries. Dave was a very generous person and the arrival of his ‘care packages’ always brought out the excitement of collecting to me.”

Steve Ogilvie, another New Zealand wrestling authority, kept tabs on Cameron over the years and broke the sad news of his death to the wrestling community. “His scrapbooks are amazing, and some of the really amazing ones were done by fans of certain wrestlers. Then, those wrestlers passed them on to Dave. There are a lot of photos and information that would have never survived.”

Cameron was born in 1933 in Wyndham, in the southern part of the country, one of six boys born to a Presbyterian minister and his wife. His family moved around a lot because of his father’s vocation, eventually settling in Gisborne. He was a terrific athlete at Gisborne Boy High School, playing basketball, soccer and rugby. On the track, he specialized in the 400-meter race, winning 17 events.

Ah, but when the boxing and wrestling bug bit, it big hard. He operated the bellows of a local blacksmith, Frank Hollis, who put gloves on Cameron and other boys for Saturday boxing. Tucked away supposedly securely at night, Cameron instead clandestinely listened to radio broadcasts of boxing and wrestling events from Australia and New Zealand, hiding under the covers and taking notes. His first published piece was on Ihakara Te Tuku Rapana, who, as Ike Robin, was a beloved amateur and pro wrestler, sheep shearer and sportsman.

“I was allowed to go behind the scenes at the boxing and wrestling and most of the wrestlers were very nice to me,” Cameron said. “I loved meeting the big-name wrestlers who came out here. I made lifelong friends with Al Costello, Jack Pesek, the Great Zorro/Jake Grobbe, Zebra Kid George Bollas and many others. I had a great life and loved the 1940s and 1950s after the war years.”

One of his early pen pals from 1948 was former National Wrestling Alliance world champion Pat O’Connor. When O’Connor, a top amateur, went to Gisborne in 1949 to wrestle in the New Zealand amateur championships, Cameron cut school to go and see him.

“I got talking with him and then it was 1956 before I met up with him again. He came home on his first visit to his homeland from U.S. Of course I was his biggest fan and in all his fan clubs, and kept all his cuttings from papers,” Cameron said.

“I must say when he came home in 1956, it was great to catch up with him and hear his stories of his travels in the U.S. I recall well being on the card as an amateur and Pat produced from his bag a strip of cards from all the states in the U.S where he wrestled. He said he needed a different license for each state. He was immensely popular with the ladies as a good-looking young wrestler with a terrific body and he could fly around the ring.

Cameron took a stab at pro wrestling in England around 1958 for Dale Martin promotions, but though he met his wife Shirley in London, he was not stout enough by the standards of the day and turned to journalism, publicity and photography.

He corresponded with fellow enthusiasts such as Tom Burke, Burt Ray and Jim Melby, and publishers such as Nat Loubet and Lew Eskin. Among other publications, Cameron had regular bylines in Fight Times, Ring magazine, Wrestling Revue and Wrestling Monthly, where he penned the introductory North American piece on “Monsieur Eiffel Tower” — André the Giant, or Jean Ferré at the time.

“I first came across this giant of a man doing the rounds of the English wrestling halls in 1969. He was a big man, but rather skinny, and he could move around the ring. I immediately wrote and told Steve Rickard, the New Zealand wrestler and promoter, about this giant from Grenoble in France and sent his picture also,” Cameron said.

The command from Rickard — get him to New Zealand and Singapore, where Rickard co-promoted with Hungarian wrestler King Kong. “Anyway, I was unable to contact the French giant as he was only on a two-week visit, and besides, his English at the time was very limited.”

Cameron did speak with him at London’s Shoreditch Town Hall the night he wrestled Jim Hussey, father of “Rollerball” Rocco. Though built impressively like the swimming champion he was, Hussey was dwarfed by his foe, Cameron said.

“Andre the Giant confided in me, and that was before he went to America. He was always worried about getting his money back to France… We in New Zealand were very lucky to see the giant before he hit New York and was snapped up by the WWF.”

Cameron became a mentor of the mat to another emerging generation of wrestling aficionados. Ed Lock of Australia and Matt Farmer of DEFY Wrestling in the Northwest said Cameron was exchanging notes and information with him when they were youngsters. “I have known Dave since the late 1960s. We began corresponding back when I was a young teenager. Dave was a lovely gentleman and a great historian,” Lock said. Farmer called Cameron’s death “really sad. Reading this made me thing back to my first communications with him, when I was only a teenager.”

His twin loves, boxing and wrestling, are the basis for two massive and well-regarded accounts. “The New Zealand Boxing Scrapbook,” done with Paul Lewis, came out in 2014 and is nearly 300 pages of photographs and text that touches on everyone from Jack Dempsey to Barry Brown, a welterweight who knitted cardigans on the side. “70 Years at Ringside: A History of Wrestling in New Zealand” is Cameron’s account of the grappling games and the personalities he met along the way.

“Steve Rickard and I were good friends, and he did a lot for the sport here after the passing of Walter Miller, who promoted here through the 1930s, ’40s, and ‘50s. Steve let me go in the dressing rooms and take photos. I just loved sending stuff around the globe and made great friends.”

Cameron would come to be friends with the big names from New Zealand who spent time in North America, including Abe Jacobs, Tony Garea and O’Connor, plus visitors like Harley Race. So dogged was Cameron that he once located rare amateur boxing photos of Nelson Mandela, sending them to his office while he was president of South Africa. “They were mailed back to him autographed as requested,” Ogilvie noted.

Professionally, Cameron spent nearly two decades at New Zealand Sugar in addition to his vast freelancing career, and competed in distance walking for many years.

“Dave gave fans a view into our lives that most never get to see. And he always treated the business with the respect it deserved,” former women’s world champion Leilani Kai, who worked for Rickard in New Zealand, wrote on social media.

“Dave Cameron understood what that time meant — he understood the history and the people behind it,” she added. “And because of him, so many of those memories are still alive today. He wasn’t just respected by fans. He was respected by us. By the wrestlers. By the people who lived it. And that says everything.”

Cameron is survived by his wife Shirley; his son, Paul with his family, Deb, Isla and Greer; and brothers Neil, Graham, Eion, Peter, Murray and Ross. A celebration of Cameron’s life is scheduled for March 29 by H Morris Funeral Services in suburban Auckland.