New book on Japanese women’s wrestling an intriguing read

Professional wrestling hasn’t gotten all that much attention from the academic community. While many schools offer athletic programs that include amateur wrestling or arts programs that include dramatic theatre, there has yet to be any school that offers courses on how to be a professional wrestler.

That doesn’t mean that the medium can’t be studied from an outsider’s perspective, which is what Professor Tomoko Seto of Kobe College set out to do. What started out as a chance invite to see an important yet unsung figure in women’s professional wrestling history led to Prof. Seto going down an incredible rabbit role of research involving countless interviews and scouring through decades old archived sources. This personal curiosity turned professional and before long it turned into an academic paper … and then a book.

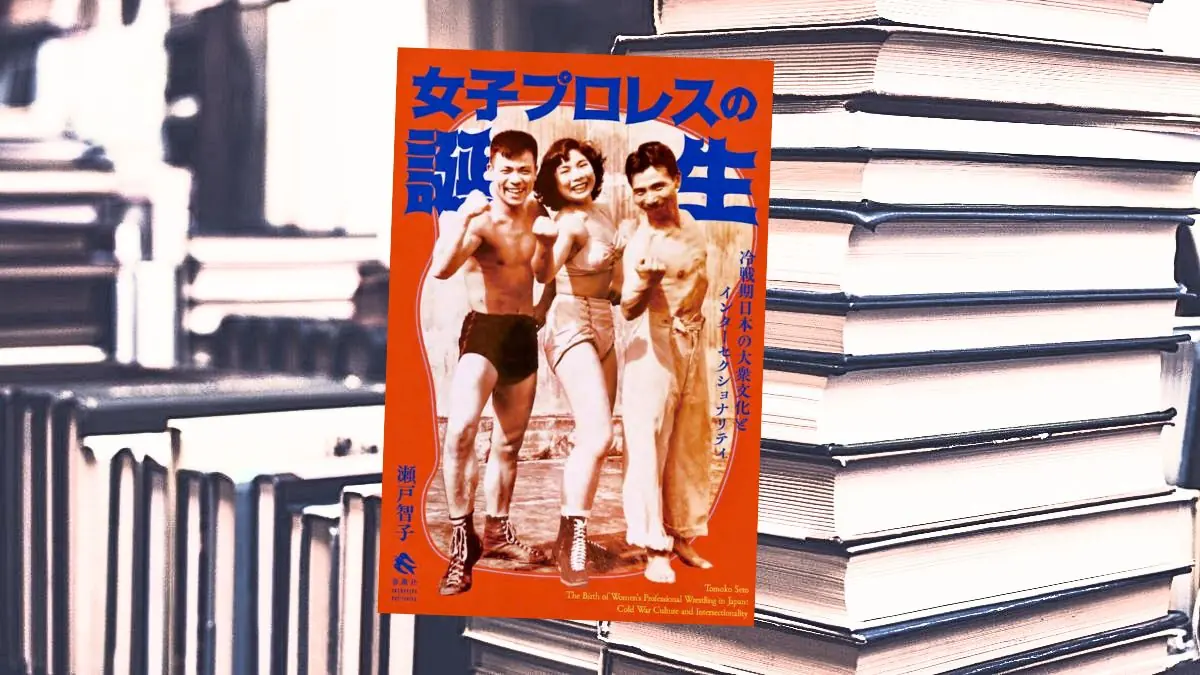

This is how Seto’s book The Birth of Women’s Professional Wrestling: Popular Culture and Intersectionality in Cold War Japan came to be. And given its both historical and ideological focus, there might not be any book like it anywhere in the world.

Although she was born in Japan, Prof. Seto moved to New York to pursue her academic career. She taught all over the world, most recently at the Underwood International College at Yonsei University in South Korea before returning to Japan and settling at Kobe College, a women’s only post-secondary institution in Nishinomiya, Hyōgo, Japan, where she now serves as an Associate Professor in its Department of Global Studies. Much of her work has focused on culture from a feminist critical perspective, especially as it has pertained to shaping post-war Japan in various stages. She never set out to create an entire academic work centered on professional wrestling, but a chance public speaking event changed that.

“It was by accident,” Seto told SlamWrestling.net. “I became friends with Sadako Igari, a.k.a. Lily Igari, the first women’s wrestler in Japan. I was living in Chicago and an old friend met her for an interview and found she was such an interesting person with curious stories.”

Igari’s experiences, which took place during a difficult period defined by poverty, limited job options, and a top-down ideological clash between traditionalist Japan and progressive American inspired liberation values, were the exact kinds of things that Prof. Seto wanted to document and share with the world.

From there Prof. Seto wanted to know more. She was fascinated with Igari’s life story, one that mixed free will and collusion, patriarchal societal expectations, the male gaze, and a lack of equal treatment among her male peers at the time, and that aforementioned clash of new and old values in a war-torn country trying to rebuild itself.

Prof. Seto described pouring over various historic and archived documents from that time including newspaper articles, excerpts of interviews, and other matters of historical record. But she didn’t do this alone: she had help from other researchers, people involved with the first iteration of GLOW, and the granddaughter of Mildred Burke to get whatever information couldn’t be found in her home country. Then came perhaps the most difficult part of her research: verifying first-person claims with an independent source to confirm their veracity. But this wasn’t always easy since, after all, much of what was said could be chalked up to carny salesmanship and embellishment of fact.

“Pro-wrestling writers who rely on interviews can be dubious in their veracity. I tend to be a bit more skeptical about wrestlers’ books,” Seto explained.

So while Prof. Seto took many firsthand accounts with a grain of salt, there were still enough experiences from Lily Igari, her family, and her co-workers to create an interesting piece of historic literature that just so happens to focus on pro-wrestling as an expression of popular culture.

This research led to Seto publishing an essay on the subject: From the Stage to the Ring: The Early Years of Japanese Women’s Professional Wrestling, 1948-1956, published in the Journal of Women’s History, Volume 33, Number 3 in fall 2021. It opens with an initial summary of what Lily Igari went through. Born in 1932, Igari and her older brother served as a sort of wandering circus act that combined early vaudevillian theatrics with a certain type of physicality while in some cases featuring elements of burlesque performance like “garberbelt wrestling” based on similar performances in France from the 1920s. Igari is essentially considered the first Japanese woman to embrace professional wrestling as a career, though it doesn’t appear that all of it was completely voluntary.

After the essay was published, Seto found that she had enough research and reference material to go even further and publish a book. Gathering more information about Igari and other women’s wrestlers of her day (including Mildred Burke who came to Japan in 1954), Prof. Seto sought to do two things: publish a book containing historical details on the esoteric topic of Japanese women’s wrestling and analyze those events from a feminist perspective.

“Women’s professional wrestling was understood not as a female version of amateur wrestling, which had gained recognition as an Olympic sport at the time, but rather as a postwar adaptation and evolution of the prewar women’s sumo with a “Western-style” twist. It had more of an image as a form of entertainment or spectacle rather than a sport.” –Excerpt translated with OpenL from Chapter 1: The Birth of Women’s Professional Wrestling

She is upfront with her book’s intentions, methodologies, ideological perspective, and stance. As a historian, Prof. Seto takes a critical approach to events that occurred and seeks to understand the reasons behind them. To what extent were these women free to pursue this venture and how much of it was involuntary? What were the reasons behind the choices they made? What were the initial reactions at the time?

Prof. Seto also contextualizes as much as possible, describing the cultural zeitgeist of the people and the country and using that as a backdrop to show how women’s wrestling, a largely American export, was received when it was still in its formative years and not fully defined as a concept. The book takes a very clear academic stance and Seto notes that she uses concepts like “the feminist killjoy” to analyze events as they occurred. But these viewpoints do not diminish the content of the book nor do they limit the reader’s viewpoint either. Instead, the book flows in an event-analysis format and yet there’s enough openness in the language to allow readers to draw their own conclusions.

Incidentally, Prof. Seto’s original intention was to publish the book in English but the world had other plans. After initially putting her draft together she was confined to Japan due to the COVID lockdowns and wasn’t able to travel anywhere else. As a result, she made the decision to have the book published in Japanese instead. Though this shouldn’t dissuade any curious readers from looking for it, given that translation tools and apps are much more widely available.

And while her book does take a critical look at a medium that many people have enjoyed over the decades, Prof. Seto herself is still a wrestling fan as well. A self-described “moderate” fan, but a fan nonetheless. Though she only casually follows today’s women’s wrestling scene, she considers herself a fan of Manami Toyota in particular, which isn’t surprising since Toyota was, in some ways, as groundbreaking and revolutionary in the 1990s as Lily Igari was in the 1950s.

Whether one sees the world from a feminist viewpoint is a matter of personal difference. But what cannot be denied is that Seto’s book provides insight into the lives of ordinary people trying to survive in extraordinary times and how different elements from different times and places melded together to create something truly novel. It’s a long read, but for the historically and intellectually curious it’s something worth investing in, especially as knowledge of professional wrestling continues to grow and change.