Jim Londos was a modern-day Jason. Lovers of Greek mythology recall that Jason was an unconventional hero, a young adult denied his rightful share of the kingship of Iolcos by his duplicitous half-uncle Pelias. When Jason appeared before Pelias seeking his inheritance, the ruler agreed to hand over the throne on the condition that Jason retrieve the Golden Fleece of a fabulous ram from Colchis.

Summoning his team of Argonauts, Jason retrieved the fleece against all odds, yoking fire-breathing bulls to plow a field, seeding it with dragons’ teeth that sprouted into warriors and pitting the warriors against each other to the death by the simple device of tossing a rock in their midst. His exploits are celebrated in the epic poem Argonautica, and, though he did not come to a happy ending, his winding expedition of persistence, valor and purpose remains a classic Greek myth.

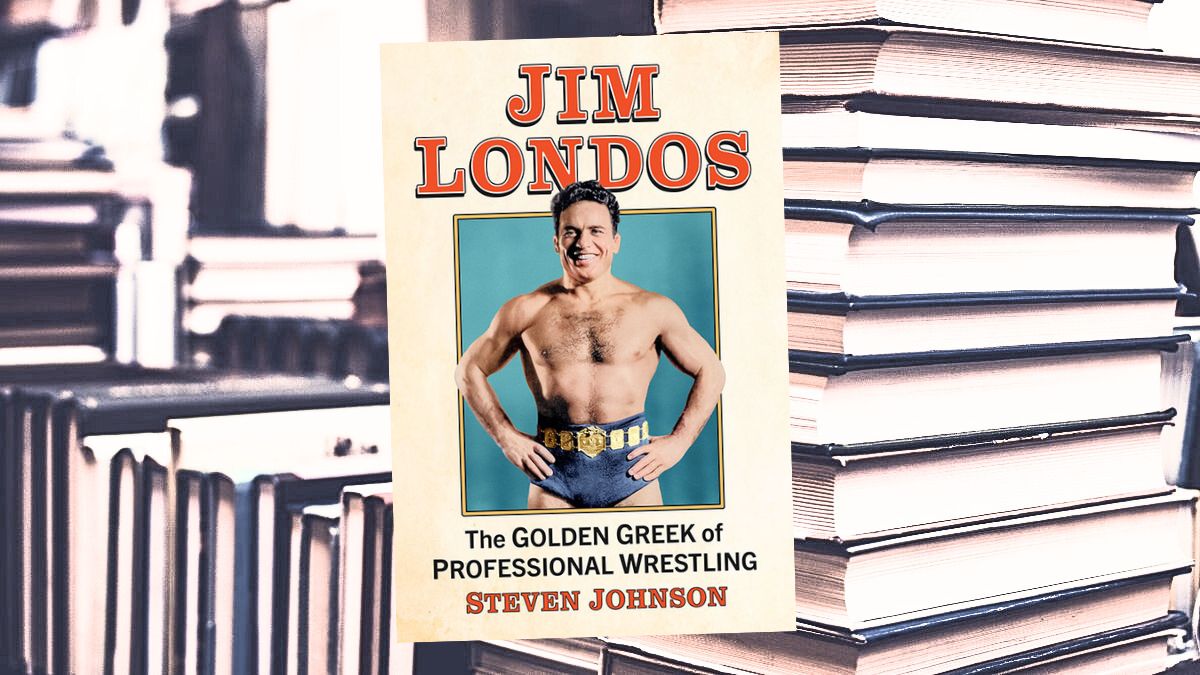

So too with my book Jim Londos: The Golden Greek of Professional Wrestling, published today, December 19, by McFarland Books. It is possible to strain the analogy but the parallel tracks between Londos and Jason are striking — and Londos is no myth.

With a confidence that belied his years, Londos sailed as a teenager from Greece across the Atlantic in search of identity and approval in an unfamiliar world. Londos’ quest also centered on gold, specifically a gold championship belt that he felt would bring acceptance from a father who disavowed him. Along the way, he encountered thrilling adventures, backstabbing characters — Scylla and Charybdis had nothing on wrestling promoters of the Depression era — and giant beasts like the always dangerous Strangler Lewis who relished the possibility of doing him in. Just as Jason had his Argonauts, Londos recruited a cadre of partners and supporters, mainly Greek ethnics, and formed unholy but necessary alliances (see Medea) in the quest for his Golden Fleece.

With a confidence that belied his years, Londos sailed as a teenager from Greece across the Atlantic in search of identity and approval in an unfamiliar world. Londos’ quest also centered on gold, specifically a gold championship belt that he felt would bring acceptance from a father who disavowed him. Along the way, he encountered thrilling adventures, backstabbing characters — Scylla and Charybdis had nothing on wrestling promoters of the Depression era — and giant beasts like the always dangerous Strangler Lewis who relished the possibility of doing him in. Just as Jason had his Argonauts, Londos recruited a cadre of partners and supporters, mainly Greek ethnics, and formed unholy but necessary alliances (see Medea) in the quest for his Golden Fleece.

Yet history has missed the boat on Londos. There are a lot of reasons why, among them the fact that his choice of careers drew smirks and sneers from large swaths of society during the last 100 years. But he intrigued me because his life and his quest seemed like the wrestling version of the classic Jason and the Argonauts movie. He was the unvanquished hero who went out on top, never formally losing the world wrestling championship he fought so hard to win. He had a fine family at his sprawling ranch near San Diego, contributed to civic causes and always would find work on his farm for some down-and-out wrestler. His name still stirs emotions among those of Greek heritage who heard tales of his prowess, like Jason, from their parents and grandparents.

I started examining Londos more years ago than I care to remember, and the book has undergone a number of guises. At various points, it was an exploration of immigrant athletes, a tome on the wrestling scene of the 1930s and a narrowly focused look at wrestling feuds of the era, Londos and Lewis foremost among them.

In the end, it is all of the above because you cannot tell the story of Londos’ rise from absolute obscurity to the top of the wrestling and sports market without covering all the bases. That’s a large reason why the project has taken so long. When Greg Oliver and I have written about wrestling in the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame series, we’ve tried to tell readers who these men and women are, and why we should care about them. Old clippings and results get you part of the way there, to be sure, but you need to go to extra lengths to explain someone like Londos, who had a 45-year career on the mat.

The challenge is that we are talking about wrestling, where the truth historically has been handled like a hot potato, tossed around and around until it lands on the ground with a thud. So to tell the story factually and accurately, I interviewed scores of people who had contact with Londos, including his daughter Christine, who graciously helped with documents and photos.

I traveled from library to historical society around the country, especially spending days at Notre Dame, where Greg Bond oversees the fascinating and overwhelming collection of Londos hater Jack Pfefer. That was just the North American part of the equation. Historians Lib Ayoub and Phil Lions helped me with clippings from newspapers in Athens, whereupon I employed a tremendously talented translator and researcher named Vasiliki Moutzouri whose work put Londos in a whole new light.

I shared some of her translations with Phil in Bulgaria and we were dumbfounded. Londos in Greece was like Michael Jordan and LeBron James and Muhammad Ali rolled up in one. Londos’ treatment by the Greek media thus is an important part of the book and that led me to look at the Greece in which Londos grew up. Professor Emeritus Alexander Kitroeff of Haverford University was an enormous help there.

What I found was that Londos, like Jason, would have been a remarkable story if he never set foot in a ring. He traveled as a 15-year-old on a slow boat from Greece. He rode the rails across the country, a hobo, finally settling in San Francisco where the climate resembled his native country. Then, like hundreds of thousands of Greek immigrants — the nation lost one-seventh of its population over a quarter-century — he got a job and started a new life abroad.

Professional wrestling in America in the early 20th century was hardly more profitable than farming in rural Greece unless you were George Karachino, the “Terrible Greek,” prominent in national print ads for endorsing a line of pure malt whiskey as a solution to indigestion. Like most wrestlers, Londos was his own promoter, barnstorming from town to town, getting a job, challenging the local tough guy and arranging for a match, often with wagering, since that was a prime source of income for wrestlers of the time.

Little by little, with determination and a bit of luck, he became sport’s biggest draw. One example of what he meant to the business — promoters ran Madison Square Garden just five times with tiny crowds in the two years before Londos won his first title. With Londos at the helm? Four straight sellouts of 20,000. His last match there was in early 1935 and only one of the subsequent 21 cards at the Garden hit the 10,000 mark before it went dark to wrestling in 1938.

That was 90 years ago but I submit it is still relevant today.

Wrestling is about making people care — care on an emotional basis and on an intellectual basis about the men, women and contests they are watching. With a variety of novel methods and techniques, Londos did that better than anyone before and few since, drawing fans who would not have crossed the street to see a couple of guys in black trunks lock up. He was a wrestler, yes, but an educator and a psychologist who told a story in the ring, one that audiences took to heart.

As an industrialist told him after a match, “You taught us tonight how to be the master of the situation you create.” It may have been 90 years ago, but the instruction Londos provided and the clues he left for generations of wrestlers are timeless as the classic tale of Jason, and I’ve tried to reflect them in this work.

Jim Londos: The Golden Greek of Professional Wrestling is available at a 20% discount through Dec. 31 at McFarlandBooks.com and also available through retailers such as Amazon and Barnes & Noble. I also will have copies in person at 2025 events such as the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame in Waterloo, Iowa, and the Cauliflower Alley Club reunion in Las Vegas.

RELATED LINKS