Preserving footage of classic professional wrestling isn’t exactly God’s work but I’m willing to go on record as saying that it’s awful darn close.

It’s a sad truth that maintaining an accurate record of their business was never all that much of a priority for the men running the show. Too often, in fact, they considered the business to be all too disposable. Too often, the people responsible for the sport we all love have considered it disposable. Nowhere is this truer than when it comes to footage from what’s now known as the territory era.

A reliable presence on local television had become a crucial element to any successful wrestling promotion beginning by the end of the 1950s. By then, most promoters had come to rely on broadcasts, filmed either during regularly scheduled events or in an area studio, to attract paying fans to live shows. Though it could vary from territory to territory, generally, weekly broadcasts ran first in the promotion’s home city. They were then intercut with material, usually interview segments, that were localized for each of the areas on the touring circuit. The tapes were sent out to be broadcast in each of these cities, ultimately making their way back to the promotion’s home city. This process was known as “bicycling,” and each time a tape would complete the circuit, the promoter would, much more often than not, record new a new show over top of the old one, wiping the slate clean. Reusing the tapes was primarily a way to save money, the footage having been deemed worth less than the pricey media that it resided on. When a territory closed its doors, any footage that might have survived was too often lost in the chaos of bankruptcy or thrown in the garbage.

If a territory was recording weekly, which was hardly unusual, accounting for reruns and weeks off, that meant roughly between 20 to 30 shows a year that were committed to tape and then permanently deleted. Over the life of each promotion, that’s hundreds and hundreds of hours of professional wrestling footage lost. This is all without considering the live shows that went on nightly, of which only a tiny fraction were ever filmed. It’s head-spinning to try and get your head around just how much wrestling was going on between, say, 1950 and 1970, and how little footage of it exists.

This began to change by the late-1970s, when home video recorders became more accessible. According to historian Scott Teal, a small group of fans with access to recording devices, began to tape their local wrestling program and offer it for trade or sale through wrestling magazines and newsletters. As is often the case with pro wrestling, fans valued its legacy much more than the people who controlled it.

This wasn’t exactly the case in the territory controlled by Portland, Oregon-based promoter Don Owen. There, the footage produced as part of Owen’s weekly television program was preserved not by a local fan, but by a local wrestler.

Buddy Rose (Paul Perschmann) was a charismatic and physically gifted athlete and performer. He began working for Owen in 1976, and soon put down roots in the area. He became a local sensation working an egotistical “Playboy” character. This flamboyant, cocksure persona was intended to create an awkward and sometimes humorous juxtaposition with Rose’s soft, undefined physique. Though in later years he would play the character for little more than cheap laughs, as with the now infamous “Buddy Rose Blow Away Diet” from his early-1990s stint in the World Wrestling Federation, in his prime, it was magical.

“I remember as a kid seeing Buddy and going, ‘What an asshole,’” says longtime Portland wresting fan Rich Patterson. “I mean, he was like this spoiled kid, and just arrogant, and you wanted to hate him. You wanted to see him get his clock cleaned.”

Rose was an early adopter of home recording technology and regularly taped the weekly Portland wrestling broadcast, likely to study his own matches. In time, he would have a VHS machine installed in the van he used to travel from match to match. He was known to study tapes religiously, critiquing his performance for what was and wasn’t working. “He saw the importance of having this footage,” says Kerby Strom, another Portland-based wrestling fan who, along with Patterson, has played an important role in preserving the area’s history.

Owens’ show was broadcast weekly on Saturday evenings on Portland’s KPTV beginning in the early-1950s. By the time Rose came to the territory, it was syndicated throughout the Pacific Northwest. At times, tapes were sent as far as Alaska via plane. “It doesn’t appeal to bankers and lawyers,” Owens was to have said of his show. “It’s for the mill workers, the farmers, the working class, the old people in nursing homes.”

This timeslot was the lynchpin to Owens’ success in promoting shows at the Portland Sports Arena, a one-time bowling alley in North Portland that he purchased in 1968 and converted into a 3,000-seat venue. His weekly Saturday evening show was broadcast live from the arena up until roughly 1979, when it was switched to running on a tape delay to accommodate a change in the program’s timeslot. When the show finally went off the air in December 1991, it was one of the longest running weekly shows in American television history.

A veteran of the Portland radio scene, Patterson befriended Rose in the early 1990s. When he casually mentioned that he wished he could rewatch classic footage of wrestlers like “Moondog” Lonnie Mayne, who’d been a star for Owen before dying in a 1978 car accident, Rose replied casually, “I have some.”

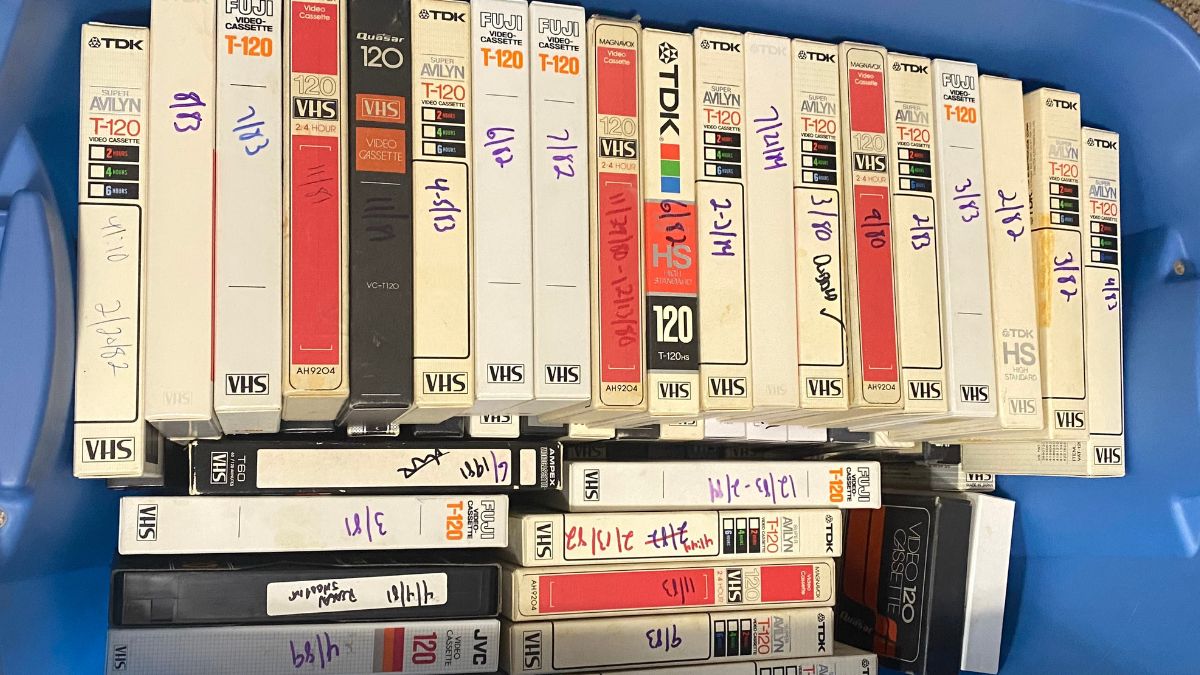

“He took me into his garage and showed me this huge duffel bag of old tapes,” Patterson recalls. “I look through them, and sure enough, there’s one label on there that says, ‘Buddy/ Mayne, 11/ 77.’ And it’s like, ‘Oh God, I gotta see this.’”

Some of the tapes in the bag had turned gray, from years of mold and mildew collecting on them. Rose had planned to throw them away but gave them to Patterson instead. After Rose’s death in 2009, Patterson received a call from Rose’s widow, informing him of the existence of another roughly nine hundred tapes that Rose had held onto. If Patterson didn’t take them, she told him, they were headed to either the recycling plant or the Goodwill. Patterson opted to take the collection home. “I’m not going to let somebody tape over a Jay Youngblood-Buddy Rose strap match with Dancing With The Stars,” Patterson jokes. “Can’t let that happen.”

While the majority of the footage was on the more accessible VHS format, Rose had recorded the oldest footage using a Quasar VR-1000, a predecessor to both VHS and Betamax machines, which relied on the antiquated VX videocassette format. Patterson acquired a Quasar machine from a collector and found a shop in Portland that could get it into working order. “Playing these tapes,” he says, “all this grime would come off onto the heads, and it stopped running. So, I’d have to take it into this place again and pay another $99.99 to get the heads cleaned. I had to do that maybe 15 times.” The footage Patterson recovered is what makes up almost all of the surviving footage from the Pacific Northwest from between 1977 and the territory’s demise in 1991.

“Rich’s contribution with salvaging those tapes was just incredible,” says Strom. “When people refer to [Portland footage of] Buddy Rose and Roddy Piper, they’re referring to that footage and we have Rich Patterson to thank for that.”

Strom has made his own contribution to preserving wrestling history. Not only is he working with local fan Ken Hamblin to digitize and release classic Super 8 footage filmed between 1978 and 1980 in Tacoma, and Seattle, he also recently acquired roughly six additional hours of Super 8 footage which he plans to make available. It contains a who’s who of territorial greats: Jack Brisco, Jimmy Snuka, the Vachons, Dory Funk Jr., Jerry Graham, and Jesse Ventura.

A musician by trade, Strom also maintains a large collection of photo negatives from multiple area photographers and inherited a number of items from Buddy Rose’s widow. “It’s fun to document this stuff and curate the history,” Strom says. “If I can come across footage that nobody has ever seen, that’s just gold.” [SlamWrestling’s Greg Oliver wrote about a visit to Strom’s collection: Mat Matters: Immersed in Portland Wrestling for an afternoon.]

Saving footage that otherwise would be destroyed is expensive and time consuming, assuming you’re one of the lucky few to even find the footage in the first place. While it’s a general truth that the majority of people involved in preserving wrestling history are more than willing to share information openly, it can still be frustrating and disheartening to see your work dumped out on the internet for free and without attribution, like it was just so much more “content.”

The Portland territory was one of the more underappreciated National Wrestling Alliance (NWA) outposts. Though it was a proving ground for a number of performers who would later go onto wider fame, it was largely overlooked by the east-coast wrestling magazines. Patterson has posted some of his footage to YouTube, as well as made it available to former wrestlers, including Rip Oliver and Roddy Piper, who otherwise had little visual record of their time in Portland.

“It’s my way of giving back to these guys who busted their asses and didn’t make a whole lot of money,” Patterson says.

He also sells the complete set of recordings, over 400 hours in total. “This is stuff that we’ve never been able to see before,” Patterson says. “I don’t think a lot of people knew a lot about the Portland territory. They may have known that guys like Piper and Ventura and Snuka got their start here, but they never saw any of the footage. And through this and what I’ve saved and shared with people, they’ve been able to see how great this was.”

NOTES: Kerby Strom will be premiering parts of his recently recovered footage at Portland’s historic Hollywood Theatre on September 30. I’ll be on hand to host a screening of Andy Kaufman’s I’m From Hollywood and to speak with the film’s co-director Lynne Margulies. More information is available here.

To contact Rich Patterson about classic Portland footage, email portlandwrestlingvideo@yahoo.com

TOP PHOTO: A box of VHS tapes that Rich Patterson got from Buddy Rose. Photo by Rich Patterson