Ted Boy Marino will die tonight, in the ring or in the streets.

Ted Boy Marino, the trim beauty in tiny togs, tinier than the Brazilian sunga bathing suit, with no weapon to defend himself and nowhere to hide it if he did.

Ted Boy Marino, who travelled across the ocean in the hold of a ship, across South America with one arm. And tonight, Ted Boy Marino, the idol of so many, his face a nightly fixture on television, stands across the ring from a hooded fiend. This is the man who will scythe down Ted Boy Marino tonight. Verdugo, the masked killer.

Why does Verdugo wear the mask? The first masked wrestler supposedly wore one to hide his French nobility, as it would be unseemly for royalty to debase themselves by grappling on the floor with commoners. Others hid their face because no challenger would knowingly face them. To work after losing a leave-town match or while under suspension. To show pride. To confuse. Or, in the case of Verdugo, the quite sensible reason that he was suspected of committing several murders and did not want to be caught by police watching TV.

This is the man who would kill Ted Boy Marino tonight. If not in the ring, then in the locker room, on the beach, or out in the streets of Rio de Janeiro. Because that’s what murderers do – they murder.

Buzzing in the streets, “Ted Boy! Teddy Boy!”, as people gathered outside appliance stores to watch televisions turned towards the glass. Young voices crying out when Verdugo grinds Ted Boy’s face along the ropes, cheering for Ted Boy’s balletic leaps as he uses his quickness to avoid Verdugo’s clubbing offense.

The pace of the action is up and down, strangers experiencing joint passion on the sidewalks without inhibition. Joint Brazilian passion without music or dance, without Jesus or football or sunshine. The buzz is choral mourning for their hero, Ted Boy Marino, the man dying for them tonight.

This was the golden age of Brazilian professional wrestling where Ted Boy Marino ruled as the King of Telecatch.

Before he was the idol of Brazil, beamed into every wealthy living room and on the streets of every city, Mario Marino was a speck of dust.

Born on October 18, 1939, on the outskirts of Cosenza, Calabria, Italy, one month after the outbreak of World War II, his family survived the war but not its fallout. Mario’s father tried to manage as a cobbler but, as many of the children were too young to leverage for economic survival, the Marinos could not maintain business enough to outlast the economic burdens of Italy’s defeat.

With Mario’s father unable to earn enough as a cobbler to support his family of eight, the Marinos sold what they could and purchased transatlantic passage in the hold of a ship. It was the best accommodation they could afford for a family of their size.

Mario boarded the boat barefoot, the son of a cobbler who couldn’t afford shoes.

The Marinos emigrated to Buenos Aires, Argentina, like many other post-war Italian families. Deposited on unfamiliar shores, the family had virtually no financial resources to support them. The Marinos had escaped Italy but not hardship.

Accommodations were spare and Perónist social benefit programs helped keep the family afloat when the Marino family cobbling business, which now incorporated the older children, still could not make ends meet. When the Marinos could afford to move into a shared room of their own in a humble boarding house, it was momentous.

Mario attended school for the first time in Argentina while simultaneously working for his father. Outcast among his peers because of his Italian accent and different cultural and educational background, Mario did not fit in easily. Even school athletics were not a fast track to acceptance, as it has been for many other athletic kids before and after. For example, Mario’s slight frame and lack of familiarity with the rules meant he was unable to shine in football (soccer) despite his natural quickness and agility.

Marino’s natural athleticism was unquestionable, and his skills would eventually find a natural marriage with telecatch, but the shy boy with the heavy accent needed time to mature and find a place where self-confidence feels self-evident.

He found that place in a marmelada, the slang term Brazilians used to dismiss wrestling as a fake.

He found that place in a coordinated fraud.

He found his place in pro wrestling.

Televised wrestling was as common as all television programs in Marino’s Argentine youth. Or rather, televised wrestling was rare in that all television programs were rare.

There were few television stations in operation, and none broadcast all day. Stations went on the air in late afternoon and ended before midnight. This limited broadcast schedule was consistent with the way television was being consumed. Receivers were still very expensive, so it was customary for a street’s wealthiest, or flashiest, resident to invite neighbors around to watch that evening’s entertainment together. Crowds would also form in bars or outside electronics stores, who always had a television pointed towards the street. Stepping into the street because a sidewalk was crowded with TV watchers was a common annoyance.

TV signals don’t obey political borders so the Argentine television audience extended beyond the geographical border of Argentina. Buenos Aires, Argentina’s broadcasting hub, is geographically close to Uruguay and many Uruguayans were able to tune in and watch these Argentine broadcasts. And from the mid-1950s onwards, Uruguayan television broadcasting from Montevideo began to cross over into Argentina, giving viewers in both countries access to both broadcasts.

Entertain and survive; entertain to survive. This was the playbook in both Argentina and Uruguay. Short broadcasting hours meant that only the most popular programs would be broadcast regularly, and tight budgets meant there was little room for experimentation. Sponsors wanted to mitigate risk in a nascent industry, so economic elements like low production overhead were the principal concerns. Enter pro wrestling.

Televised wrestling programs in Argentina and Uruguay were filmed and produced by the TV stations themselves, who used intermediaries to secure wrestlers for the live broadcasts. Pro wrestling was so popular (and inexpensive to produce) that both sides of the border felt they had to lean into the demand. That created a brand new problem in South American television wrestling: scheduling conflicts.

None of the wrestlers were contracted to specific TV channels, so programming wrestling to run head-to-head with a cross-border competitor could not only split the audience – it could split, or drain, your own talent pool. Imagine intentionally creating the Night War without exclusive contracts.

Advertisers were a further consideration because Buenos Aires and Monteviedo relied on overlapping sponsors. If both shows were broadcast simultaneously, so the thinking went, the sponsors could choose to follow one station, and leave the other hanging. That all-or-nothing approach may have worked if one broadcast was superior but with none of the talent exclusively contracted, a strong-arm approach could have led to a sponsored show without any top talent. No sponsor wanted to be left in that position either.

It took regular maintenance to ensure pro wrestling broadcasts were never in conflict keeping advertisers and top talent satisfied. In that sense, it was like an inverse of the Monday Night Wars – with top promotions working in concert to produce the same level of popularity, or higher – and Ted Boy grew up saturated in it.

These pro wrestling shows reshaped Mario Marino’s brain. This is what he wanted to be. Mario’s inner wrestler hatched and wanted to fly.

In many ways, Mario was perfect for the role of professional wrestler: athletic but outcast, unsatisfied by conventional success, skilled beyond his peers in certain ways but deficient in others that made him deeply appreciate affection from those more flawed than him. And all just accompaniments to his tenacity.

Skinny Mario didn’t see a professional’s body reflected in his mirror, so he set to work developing his physique. He sculpted himself at the gym of Club Atlético Independiente de Halterofilia, a Buenos Aires multi-sport athletic club known primarily for its soccer teams. Over time, Mario began to gain respect from gym regulars for his attitude and the skepticism gradually faded away. It was at Independiente that Marino was supposedly discovered by Martin Kardagian, god of Argentine pro wrestling.

They were similar, Martin and Mario. Kardagian’s family emigrated to Argentina too, fleeing a Turkish death machine feeding on Armenians. Both had fathers who had been unable to keep their families fed. Both were blonde. Neither dumb.

Maybe Kardagian saw a bit of himself in Marino or maybe he just saw money. Either reasons would have been good enough.

Everyone in the Kardagian universe had an over-the-top gimmick. The Viking. The Hippies. The Mummy. It was Kardagian’s mind that birthed the wrestling clowns and the invisible man, so once Mario was in the fold, he needed his own gimmick.

The “Teddy Boy” was a 1950s London subculture that quickly spread throughout the UK. Teddy Boys were young men who liked American rock music and wore Edwardian-style leftovers purchased at thrift shops. This led to the nickname “Edwardian Boys” which was first shortened to “Teddy Boy” in a September 23, 1953 Daily Express newspaper headline. Kardagian supposedly read about Teddy Boys in a magazine and kept the idea with him until bestowing the gimmick on Marino.

Once introduced, Ted Boy Marino began a quick ascent and by 1962, he was a top star on the wrestling shows on Channel 9 from Buenos Aires, and on Montevideo’s Channel 12.

He would always play the babyface in peril, regularly subjected to vicious beatings by thick, hairy man-beasts. In contrast to these brutes, Ted Boy played the cool lead, maintaining a calm demeanor that drove his more-exaggerated opponents further up the wall.

It could have been one of these in-ring barbarians who started a rumor that stuck with Ted Boy throughout his career, that Ted Boy would pay his opponents not to damage his face. The rumor was strange because it was common knowledge that wrestling is predetermined, but it was floated among the public nonetheless. It sounds unlikely, if only because you can imagine a goon taking the money and then breaking Ted Boy’s nose anyway, yet the rumor may have persisted in large part because the wrestling audience bought into Ted Boy as something valuable and worth being protected.

Unfortunately, few were protected from a prolonged economic crisis that hit all Latin America in the first half of the 1960s, leading broadcasters to slash their wrestling budgets and Ted Boy to consider his future, a future that would lead to Brazil.

The first television broadcast of Brazilian pro wrestling was “Feras do Ringue” on TV Record Channel 7 in 1959, beginning a 20-year run of pro wrestling on the station. From that point onward, professional wrestling was known in Brazil as telecatch, a portmanteau of “television” and “catch-as-catch-can,” itself a term for a bygone form of wrestling that resembled the Brazilian product in only the haziest of outlines.

In June 1961, Martin Kardajian made an appearance at the Festival of Five Fights at Rio’s Ginásio do Maracanãzinho, where he was submitted in the first round of a shoot by Carlson Gracie. The contest was short, but Kardagian’s pre-fight heel promos left a big impression. Even with strenuous opposition from luta livre afficionados, the “real” fighters, the unique exhibition that is pro wrestling had taken hold in Brazil.

From April 1964, Brazil’s political isolation helped shield it from the surrounding economic devastation. Though it was mortgaging the economic security of future generations to satisfy the present, the military government kept Brazilian cash circulating. So when Brazilian wrestling manager Teti Alfonso arrived in Argentina in 1965 looking for pro wrestlers, he arrived with pockets full of comparatively free-flowing cash.

Alfonso’s 1965 scouting trip could not have come at a better time for Ted Boy Marino, and the timing could not have been worse. Alfonso was there on a smash-and-grab operation looking to take wrestlers back to Brazil ASAP. There was a wrestling boom starting – by 1967, telecatch was broadcast on five major television channels – and Alfonso needed able bodies. Ted Boy was charismatic and athletic, though not presently able-bodied. He had suffered a broken arm during a recent match and was still nursing the injury.

That Alfonso was ever swayed by Marino is remarkable itself. Ted Boy was in no condition to wrestle, there were no highlight reels or compilation tapes for Ted Boy to show Teti, and Alfonso was not in Brazil to find investments; he was there to find employees. Yet the temporarily one-armed Marino was able to earn himself the least secure deal available, a one-year contract without any rollover or extension provisions.

Mario Marino risked it all. By this point, the once-modest family cobbler business had blossomed into an entire factory in which Mario had a share, providing concurrent economic security while Ted Boy was travelling throughout Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay at the top of the cards. This non-wrestling income may have sustained Marino during that difficult time out with injury, but a quiet life was not enough for the big dreamer.

Marino sold his share in the family business to his brothers, and moved to São Paulo, off to live the rest of his life in Brazil.

Most telecatch matches followed a familiar pattern, one Marino had learned in Argentina. Ted Boy was the pure babyface, working cleanly and using is speed and agility to execute flying kicks and head scissors. And the head scissors. And the head scissors.

The flying head scissors was Marino’s most frequently used maneuver. It was impressive, the way Ted Boy would leap into the air and clasp his opponent’s head between his ankles, whipping down from the side and causing his opponent’s head to be drawn downward (though usually ending in a rolling back bump). The maneuver would grow progressively less exciting with every head scissors Ted Boy would execute, and he executed them often. His most common spot was a series of Carpentier-like head scissors with the opponent taking the move, popping up and feeding right into another. Up and down action. Maybe a bit repetitive but far different than the less flashy luta livre.

There was little mat-based or amateur wrestling, not that Ted Boy was uniquely excellent in either. Remember that Ted Boy was promoted quickly, and young men who are rocketed to the top of the card with little experience do not always circle back to refine their basics. That’s one reason why match structures resembled a kind of controlled chaos, focusing on drawing emotion from the audience rather than zealously adhering to a more naturalistic, sporting style.

To get the heat, Ted Boy’s opponents would absolutely maul him with hammering strikes and blunt kicks. The heels weren’t smooth and that was the point, to draw the contrast to the silky or more clever good guys. The most finesse these monsters would show was while squeezing lemon juice into Ted Boy’s eyes.

The heel’s first step was distracting the referee, maybe with a ref bump or a ringside bruhaha instigated by the heel’s second. Then the attack would be on. As Dusty Rhodes would have described it, Ted Boy would be clubbered with plunder over and over. Usually, the weapon would be a chair. Less frequently, a brick. A fiery comeback with multiple flying head scissors followed and Ted Boy would rebuff the monster back to the rogue’s gallery.

And these opponents were a classic rogue’s gallery.

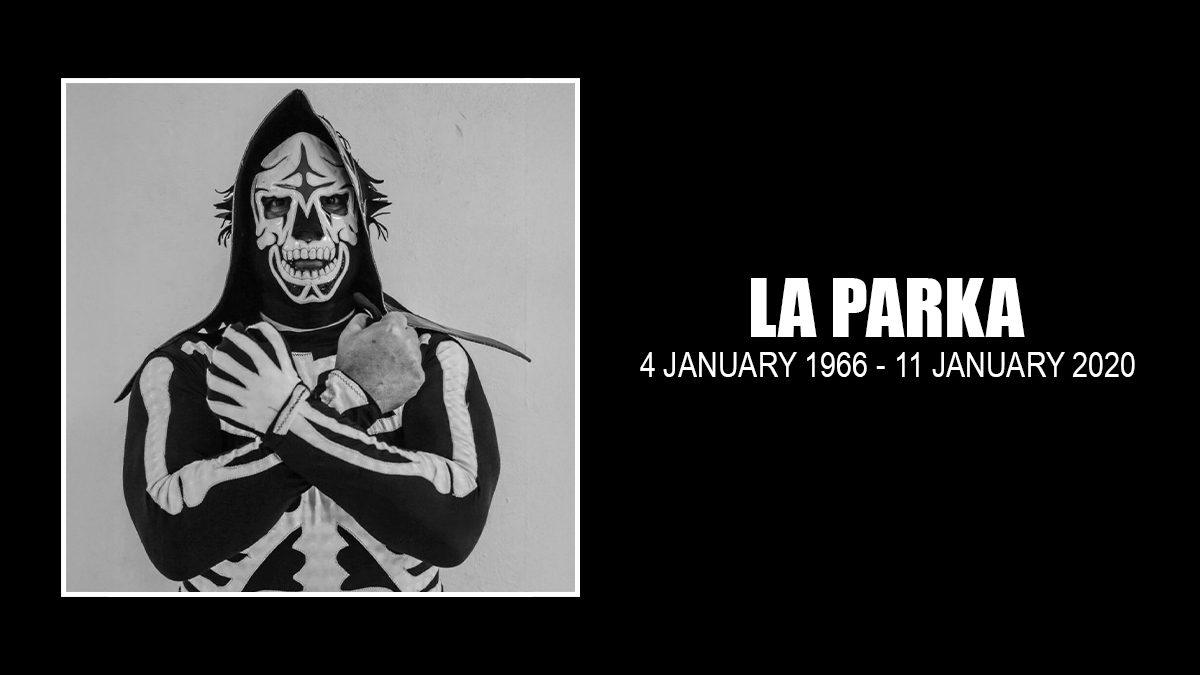

There was Verdugo, the masked killer. Dressed head-to-toe in black, a monster heel with a white skull image on his face and a second spread across his chest like a corrupted Superman.

Verdugo was villainous in a pantomime way, pursuing his opponents at a steady glacial pace hauling one stiff leg behind him, in the theatrical tradition of a deformed soul deforming the body. Watching through today’s eyes, the violence is farcical but, at least for some at the time, the masked Verdugo presented a very real threat.

The character was created by Argentine Angel Pedro Bofa, who began wrestling in Brazil as “Ali Bunani,” a successful gimmick in its own right that allowed Bofa to work on TV Record, Excelsior and Globo. Yet Ali Bunani is a footnote in Bofa’s career when compared with the success he created with Verdugo, possibly the greatest Brazilian heel of all time.

In the top mix with Verdugo was the character of Fantomas, portrayed by so many wrestlers that it can be difficult to trace the lineage past its early phase.

The character was first developed for telecatch by Vicente Jose Pometti of Argentina, who himself was essentially drawing from Pierre Souvestre and Marcel Allain’s pulp creation The Phantom. Popular in pre-WWI France, The Phantom comics and dime-store novels had been translated and circulated worldwide by the 1960s, and more than a few wrestlers trace their gimmick’s heritage to that same pulpy paper.

Though Fantomas iconography was passed down, and stolen, over the years, certain key characteristics remain the same in every portrayal. All Fantomas are tall. They wear all black, from hood to boots, with a red-lined cape and white-fronted mask. There is also a “Fantomas style” of wrestling based around defense and counter-attacking. If Fantomas was to be highlighted in a particular match, spots were designed to highlight the character’s ability to withstand the opponent’s most severe punishment. This would lead to a finish where Fantomas would counter his opponent’s offense into a finishing hold and pin.

A counter wrestler stood out because telecatch heroes were hunks and highfliers, the villains were stalkers and savages. Both sides had limited offensive flexibility dictated by tradition but Fantomas could work with either side. This, combined with the ambiguous morals of the pulp Phantom, led to Fantomas becoming Brazil’s most popular tweener.

The versatility of the tweener character (plus many promoters’ desires to book one wrestler, dress them in a full-body suit and send them through the curtain twice) has meant that Fantomas were popping up on every local show. Scroll through the comments of every telecatch article or video posted online and you will find mentions by the niece or nephew of some such Fantomas, asking for more information.

Marino’s adversaries weren’t all strong silent types though. Aquiles the Matador was another in the menagerie of Ted Boy’s famous opponents. If Ted Boy burned the brightest, Vespaciano Felix de Oliveira may have maintained the steadiest glow for the longest time, working for decades on televised wrestling with or without the major spotlight. Always a braggart, Aquiles would antagonize his opponents pre-match, promoting his own abilities as superior. Incorporating a flashy red matador’s cape, Aquiles taunted and goaded and cajoled, with crowds reacting to each increasing boast. It was a method that still riles up fans today – draw their eyes and then belittle them for gazing.

As with all villains, the spotlight shone brightest on Aquiles when he was pitted against the country’s biggest hero. The booking was clever too, benefiting both wrestlers. Aquiles confronted Ted Boy and claimed the pretty boy hero wasn’t strong enough to take a single punch from O Matador. Strength versus speed, a classic confrontation.

In the match they built, every clever evasive move by Ted Boy gave Aquiles reason to brag, becoming more cocksure that Marino could not take a punch. Aquiles was able to gain control of the match and imperil Ted Boy using his strength, withstanding Ted Boy’s offense and frustrating the hero. Of course, Ted Boy eventually won but Aquiles proved himself in defeat by shattering expectations. The Matador could talk but he backed it up. Aquiles was no Carlos Kaiser.

And what shame was there in losing to the best? Ted Boy would always overcome the odds and triumph. It was simple, but it was popular.

Wildly popular.

Ted Boy Marino had been thrust onto Brazilian television as soon as his arm healed enough to step into the ring. There was the short television run on the show Gigantes do Ringue on TV Tupi Channel 4, but stardom hit big at TV Excelsior. The ascent was quick, and by late 1966, the shoeless boy who arrived in the belly of a ship was on the cover of Brazilian TV Guide. It was popularity just waiting to be commodified.

Producer Wilton Franco was tasked with creating a new program that capitalized on the nascent fame of Marino and another young entertainer, the heartthrob singer Wanterley “The Good Boy” Cardoso. Excelsior wanted the popular wrestler and singer on television more often, but without leaning on what brought either to recognition. No singing and no wrestling. Jacques Cousteau in the desert. Easy.

Franco brought in comedian Renato Aragão and singer Ivon Cury to round out the cast and the result was Os Adoráveis Trapalhões (“The Adorable Bumblers”), a variety show that emphasized the principals’ skills while deemphasizing their weaknesses. For example, Ted Boy hardly spoke in the first episodes because he had a thick Italian-influenced porteño accent. But linguistic impediments did not impede his broader success.

Somewhat surprising given his partial incomprehensibility, Ted Boy recorded his own record single. He sang in the popular Iê Iê Iê (“yeah yeah yeah” or “ye ye ye”) style, and it was reportedly a success though Odeon Records did not contract Ted Boy for a follow-up release. Still, a wrestler cutting a popular single, even if viewed as a novelty release, was a sign that Ted Boy Marino was breaking through into a growing youth culture.

Television. Radio. Naturally, the Brazilian film industry couldn’t ignore such a popular attraction. Ted Boy’s rising star was lassoed by film producer Herbert Richers, who cast Marino as the star in the movie Dois na Lona (“Two on the Canvas”), a script written just for him. Marino played a young wrestler with a comic best friend played by Renato Aragão, Marino’s companion from Os Adoráveis Trapalhões. Marino’s character was antagonized during the movie by Lobo, played by Roberto Guilherm, an actor who would earn wider notoriety in the later, more-popular incarnation of Os Trapalhões.

Production was not smooth and filming stopped multiple times. Renato Aragão broke his arm in an on-set accident and Richers had to wait for his workhorse actor to heal. Then the cameras stopped for Ted Boy’s wedding to Teti Alfonso’s daughter. And then lights were dimmed every time Richers ran out of funds, which happened several times. Once it was completed, the film’s release strategy was laughable by modern standards; the main stars supposedly learned of the film’s imminent release when it was advertised in movie theaters.

But despite the rocky production of Dois na Lona, no other telecatch wrestler could point to their own feature film, with or without a porteño accent.

As in Argentina and Uruguay, Brazilian wrestlers were not contracted to a particular broadcaster. Television stations broadcasting wrestling worked with managers like Teti Alfonso to bring in talent, and it was impossible for Alfonso not to realize his client was a major talent. Marino’s popularity was right there in black and white. In 1967, the magazine Revista Intervalo held a poll among its readers to determine the country’s favorite actor; Ted Boy came in third.

Working without the knowledge of TV Excelsior, Alfonso engineered a deal to take most of the wrestling talent from Excelsior to TV Channel 5 along with the show’s sponsor, the Brazilian rum Montilla. The transition led to Marino’s full divorce from Excelsior, including Os Adoráveis Trapalhões, where Ted Boy was replaced with rising bombshell Vanusa. Though the show would be successfully resurrected in the future, the version of Os Adoráveis Trapalhões that lost Ted Boy Marino was cancelled within a year.

Teti’s risky move paid off, and Ted Boy Marino was never more popular than when wrestling on Channel 5. At the height of his cross-media fame, he received approximately 2,000 fan letters per week, reportedly more fan letters than Roberto Carlos at the height of the Jovem Guarda. Even when accompanied by a bodyguard, Ted Boy could only walk the streets in disguise without being mobbed.

In 1968, Teti Alfonso sold Marino’s contract to the newly-created Globo TV station, and Globo put Marino on television seven days a week. Every weekday, Ted Boy hosted Session Zás Trás, a children’s program that showed cartoons. On Tuesday evenings, he hosted Oh, que Delícia de Show!, a variety program in which Marino presented singers and circus acts alongside actress Célia Biar.

Additionally, there was Ted Boy Contra Orion IV, where Ted Boy ran a sort of intergalactic fight camp for kids that served as a vehicle for guest stars. It was light fare but widely seen because it was programmed before the national news.

On Saturday and Sunday nights, Ted Boy would wrestle. Saturday nights in Rio and Sunday nights in Sao Paulo. The Sao Paulo show would be broadcast live, while a clip show of the past weekend’s wrestling would air on Saturday nights from 9-10 p.m.

If you wanted Ted Boy Marino in your living room, just turn on your television set and wait an hour or two. You could pass the time thumbing through one of the several issues of TV Guide featuring Ted Boy as cover model or reading profiles of him in national tabloids.

Even though footage of Ted Boy’s weekly wrestling is not readily available, his contemporaneous fame remains preserved in sticker form. Popular especially around major soccer tournaments, sticker albums are the Brazilian equivalent of American baseball cards. Children would purchase a magazine-like album and then collect stickers from blind packs to complete the blanks. Publisher Cromos Limited issued one of these sticker books of telecatch stars – Os Reis do Ringue – and no other wrestler is as prominently featured as Ted Boy. The next Os Reis do Ringue cover featured Ted Boy front and center, occupying as much real estate on the cover as the other six wrestlers combined. One multi-sport album recognized Ted Boy’s fame with the equivalent of Brazilian sports canonization – Ted Boy Marino was one of three athletes on the cover, alongside Pelé.

At his apex, Ted Boy Marino was so popular that you would need the strength of an army to make Brazilians abandon their hero.

That is exactly what happened.

By the end of the decade, Brazil’s military government was no longer an indirect friend to telecatch, keeping cash flowing and thereby helping Brazilian managers like Teti Alfonso import outside talent. Instead, telecatch had become, in the eyes of at least one official, an enemy of the people.

Following a lesser 1968 ban, Colonel Aloysio Muhlethaler, the head of the Federal Police Department’s Public Entertainment Censorship Service, issued a sweeping 1969 prohibition on broadcasting telecatch before 11:00 p.m. Justified by the occasional appearance of hardway blood on live TV, Muhlethaler argued that community morals would be better protected by restricting the broadcasts to later hours when children were more likely to be sleeping.

Now that it was illegal to broadcast telecatch in prime time, Montilla rum pulled its sponsorship and the partnership which made Telecatch Montilla the country’s most successful pro wrestling program wrapped up. Ted Boy’s novella had already concluded (Brazilian novellas are single season productions) and his variety show with Celia Biar was cancelled.

Things became even worse for Ted Boy when his theretofore unpublicized marriage became public, fracturing his parasocial relationship with many of the younger female fans who would scream for him like a one-man Beatles arriving at JFK Airport. The beautiful boy whose face graced Valentine’s Day magazine features was just some married guy now, like their dad.

Ted Boy’s fame reached its peak and now the world was different overnight. A military man – a military man! – is afraid of the sight of blood? A hero is banished because he bleeds? Has a wife? Every day on TV, Ted Boy defeated monsters and space aliens and always stood clean and proud, and the government now says it was all scandal.

What are the essential elements to pro wrestling? There are the participants, a venue, an audience, and short-lived retirements.

With telecatch banished and his star tarnished by the quick fall, Ted Boy Marino announced he had purchased a farm in the Brazilian countryside and intended to retire. He was financially well off already, having invested in shoe and shirt factories with his wrestling earnings, and he told his fans that he was prepared to assume a calmer life. That’s what he said.

Brazil’s live event circuit remained in better shape than televised wrestling, and Ted Boy Marino went on to work at least 300 matches in the decade that followed his retirement. Of them, he drew ten, lost four (Mongol twice, Malvado, and El Chasqui) and won the rest. Of course he did.

It was a phenomenal record, worked or not, in the vein of other regional superpowers like England’s Big Daddy and Great Power Uti of Nigeria, except Marino wasn’t the promoter or his brother. Ted Boy’s record signals that fans would still buy a ticket to see their hero triumphant. There would be no late-career villain run either. Marino’s meat was white all the way to the bone.

By the end of the ’70s, Ted Boy could be seen touring throughout Brazil’s less-populated interior as part of theater and circus shows, drawing crowds on his name alone.

He would wrestle well into his 40s, though he was always billed as being at least four or five years younger, no longer employing the quick succession of head scissors that made him famous. It was all character work, as you would expect, but Marino remained popular. His last recorded match was held in February 1992, at the Acadêmicos do Viradouro samba school in Rio de Janeiro, in front of a reported audience of 8,000 people.

Ted Boy retained celebrity for the rest of his life, and it turned out that his television career was not over, just his career as a television wrestler. He would appear in comedy shows as a walk-on cameo, usually alluding to his earlier fame with telecatch. For example, Ted Boy and Renato Aragão, Marino’s co-star in Os Adoráveis Trapalhões and Dois na Lona, appeared on the later version of Os Trapalhões playing painted wrestlers in a frame who would change holds when gallery-goers looked away. He was not ubiquitous anymore, though he remained an attraction. When TV Gazeta celebrated its eighth anniversary with a huge week of programming, the station advertised appearances by Paul Anka, Petula Clark, Wanderley Cardoso and, “finishing the anniversary programming in grand style, Ted Boy Marino.”

His last significant television job was on the novella Bang Bang in 2005-06. Marino is said to have felt disrespected at the way his television career ended, as he was let go days before he would have been eligible to apply for corporate retirement benefits.

Marino spent his retirement as a fixture on Leme Beach in Rio. He was known fondly among his neighbors, some of whom would join him for regular games of beach volleyball and conversation at Mariu’s Restaurant. When people stopped Ted Boy on the street, many we surprised that someone who was one of the biggest entertainment stars in Brazil – a wrestling Justin Timberlake or J-Lo – was so humble and down-to-earth. A dedicated fan of Rio soccer club Fluminense, a team he chose because they play in the same colors as Italy’s flag, the only surefire way to aggravate Marino was to slyly praise his team’s bitter rivals, Flamengo.

Death in the streets? Not with his acolytes to protect him, the acolytes who cheer and cry and always blocked the sidewalk whenever Ted Boy worked his art on horizontal canvas.

Death in the ring? Brutalize him all you want, but the squeaky-clean Adonis would always fire up for the comeback.

So who killed Ted Boy Marino? Mario Marino killed Ted Boy Marino, like Charlie Chaplin killed The Little Tramp, the creation dying with the artist. Ted Boy’s cause of death: Mario’s mortality.

The man died on September 27, 2012, less than a month before his 73rd birthday, rushed to the hospital after a stroke and succumbing to complications following emergency surgery. His heart failed – he, the heart of so many – unable to endure the rigors of the procedure.

Mario passed and Ted Boy remains, spirit free of the body. The book is written, ephemeral scripture written by flying head scissors.

In his moment, Ted Boy was as popular as any wrestler in any territory at any time. But beyond pop idolatry, Marino inspired deep passion in his fans, many who had no interest in telecatch beyond Ted Boy. It was always only Ted Boy.

Police officers told stories of having to separate fans determine to grab anything Ted Boy touched on his way from the ring. Their blood for his sweat. A trade fans were hungry to make. Anything for their hero supreme. The King of Telecatch, Ted Boy Marino.

Works Consulted

- Carrico, André. Os Trapalhões. EDUFRN, 2020.

- Domingos Do Amaral, Carlos Cesar. “Luta Livre E Inovações Narativas no Espetáculo de Pro-Wrestling no Brasil” Universidade Municipal de São Caetano do Sul, 2016.

- Domingos Do Amaral, Carlos Cesar. “Os Produtos de Consumo Da Luta Livre no Brazil” Educação, Gestão e Sociedade: revista da Faculdade Eça de Queirós, Volume 6, Number 23, August 2016.

- Drago. Telecatch. Matrix, 2007.

- Folha de S.Paulo. “Rei do ‘telecatch’, Ted Boy Marino sintetiza relíquia de outra era.” September 29, 2012

- Meltzer, Dave. Wrestling Oberserver Newsletter obituary.

- Mendonça, Renato. “Um Ringue Na Sua Sala”. Cultura, Feb 28 2009.

- Passos, Daniella de Alencar. “Os Artistas Do Ringue: MEMÓRIAS do telecatch Curitibano” (2013) XXVII Simpósio Nacional de Histora, ANPUHI.

- Ribke, Nahuel. “Telenovela writers under the military regime in Brazil: Beyond the cooption and resistance dichotomy” (2011) Media, Culture and Society. 33(5) 659–673.

- Roncoli, Daniel. El Gran Martin: Vida y Obra de Karadagián y Sus Titanes. Planeta, 2012.