On October 1, the wrestling world bid farewell to one of the last icons of a bygone era. Kanji “Antonio” Inoki, the founder of New Japan Pro-Wrestling (NJPW) and one of the most influential wrestling figures ever, passed away at age 79. Inoki had spent years battling multiple health issues, including a recent struggle with cardiac amyloidosis. His last high-profile public appearance was at this year’s Wrestle Kingdom event. Inoki made a brief appearance via satellite to commemorate NJPW’s 50th anniversary, his first appearance for NJPW in over 15 years. And while he looked haggard and weathered from his health battles, he still showed a positive attitude and “Fighting Spirit”, which has become the cornerstone of not just New Japan as a company, but of Japanese wrestling as a whole.

Born on February 20, 1943, Inoki began wrestling at 17 years old after recruited by Rikidozan – the godfather of Japanese wrestling – when he was living in Brazil after his family fell on hard times in post-World War II Japan. Determined to follow in Rididozan’s footsteps to become a big post-war national hero, Inoki learned how to grapple under the tutelage of the great Karl Gotch, who was so skilled and revered for his skill that the Japanese nicknamed him “Kami-sama (神様)”, literally, ‘God’. It was during this training and his initial work for the Japanese Wrestling Association (JWA) that Inoki met his tag partner and future business archrival Shohei ‘Giant’ Baba.

Those three names – Rikidozan, Inoki, and Baba – are widely considered to be the three biggest names in Japanese wrestling history. But their success and reputations would extend far beyond the wrestling ring and later transcended into business, and in Inoki’s case, politics.

Although Inoki (and Baba) studied under Rikidozan, their futures nearly disappeared when Rikidozan was murdered in 1963. Rikidozan was able to capture an entire country’s collective consciousness as a post-war hero who helped an aggrieved and despondent country lift themselves up out of the doldrums of a terrible war and a crippling absence of national pride. Pro wrestling in Japan, or puro, nearly died with Rikidozan… until his two best pupils went to war with each other.

Inoki wrestled for the Japanese Wrestling Association (JWA) until he was fired in 1971 after a hostile takeover of the company failed. Following his firing, Inoki founded NJPW as his own company. Meanwhile, Baba took the remnants of the JWA and created All Japan Pro-Wrestling nine months later. And with that, so began a promotional war that, for all intents and purposes, still exists today, 50 years later.

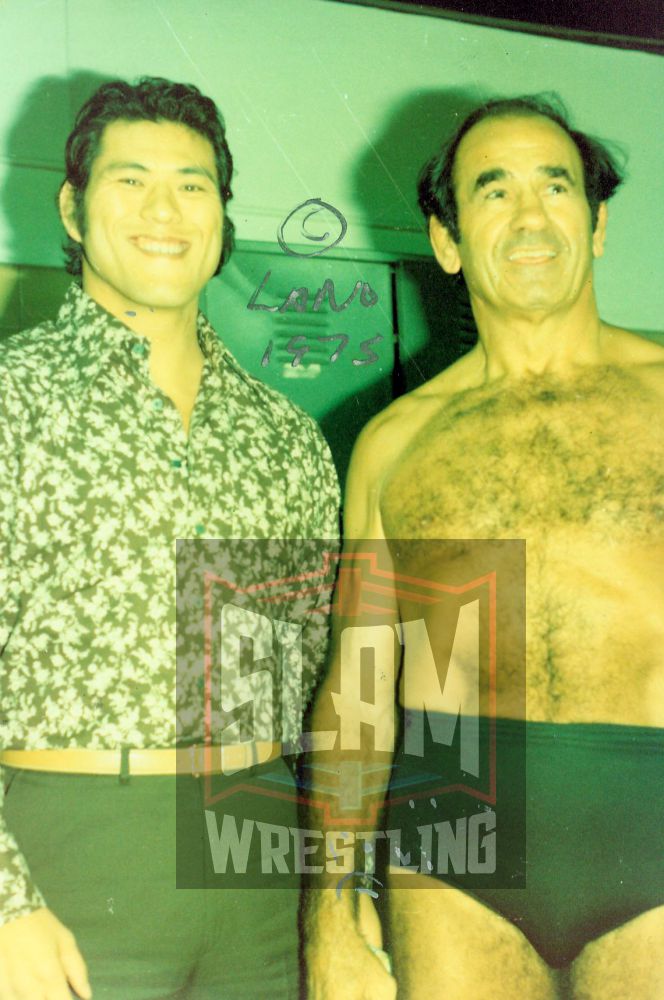

Antonio Inoki and Lou Thesz in 1975. Photo by Mike Lano, WReaLano@aol.com

Inoki built NJPW around himself and created a special wrestling style for the time. Determined to distinguish New Japan’s style from that of Baba and his NWA-affiliated partners, Inoki created the concept of ‘Strong Style’. Whereas the All Japan/NWA style was built on narrative, brawling, and more “entertainment”, Strong Style emphasized realism. Inoki wanted his wrestlers to be seen as the toughest and most accomplished combat sports practitioners in the world. With martial arts being so prevalent in Japan, Inoki wanted to make sure that those practitioners would lose should they ever call out and try and beat up his wrestlers. Thus, Strong Style came to combine amateur wrestling with martial arts strikes and throws, and a heavy emphasis on submission holds. With this new Strong Style, Inoki began an upward climb that saw New Japan reach international fame and recognition.

“Our matches were fantastic. Antonio was easy to work with and knew a lot about the American style of wrestling due to the time he spent in the United States working with Hiro Matsuda. We would go thirty or forty five minutes. We worked a thirty-minute Broadway that was named the best match in Japanese wrestling history. Nearly twenty years later they were still showing our match on Japanese television.” – Brisco, by Jack Brisco and William Murdock

Antonio Inoki in the ring at New York City’s Madison Square Garden during a WWWF event (note Vicki Williams on the left side). Photo by John Arezzi

Over the decades, Inoki beat a veritable who’s who of pro wrestling. As a rookie he faced classic icons like The Destroyer, Freddie Blassie, Ripper Collins, Gene Kiniski, Jack Brisco, Harley Race, Danny Hodge, and Dory Funk, Jr. His first match in New Japan was against Lou Thesz. He teamed with and fought against Hulk Hogan over a hundred times during the 1980s, including in a tournament final to crown the first-ever IWGP Heavyweight Champion. He won the WWWF Championship from Bob Backlund but relinquished it due to outside interference (this reign isn’t recognized by WWE, though was mentioned during Smackdown commentary after Inoki’s death). He beat André the Giant in singles combat. He wrestled on an exhaustive schedule not unlike Ric Flair’s, with many matches going well beyond 30 minutes. In fact, according to wrestling database cagematch.net, Inoki had 3,676 matches between September 30, 1960 and December 31, 2001.

An Antonio Inoki vs Muhammad Ali poster on display at the George Tragos/Lou Thesz Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame induction weekend, July 16-17, 2021, in Waterloo, Iowa. Photo by John Arezzi

And of course, he had that ‘cross-discipline’ boxing match with Muhammad Ali that ended in disappointment after Inoki was forbidden from striking and had to kick at Ali’s calves from his back. And while that contest failed to deliver in terms of quality, it showed Inoki’s undeniable skill in promoting something that people would want to see.

“Inoki had gained worldwide attention as a result of his boxer/wrestler match with Muhammad Ali in 1976. Ali thought it was a work but Inoki took it as a shoot. That idea went out the window fast. The black Muslims who were backing Ali made it clear that if Inoki laid a finger on their champ, they would kill him. That’s why Inoki lay on his back for fifteen rounds, kicking Ali in the shins so as not to use his hands.” – Bret Hart, Hitman: My Real Life in the Cartoon World of Wrestling

“In many ways, this was the biggest endeavor in pro wrestling history. It was the first national closed-circuit show, and until the wrestling boom of the 90s, no pro wrestler ever made even close to the $2.1 million that Ali made for the fight. Of course, he was promised $6 million for a worked match to put Inoki over, and up until that point in time, his biggest payday was a boxer was $5 million.” – Dave Meltzer on the Ali/Inoki Fight, Wrestling Observer Newsletter, April 1, 2009

But it wasn’t just big names for Inoki; his career is one long catalogue of championships and accomplishments. He was won singles and tag titles all over Japan and in the United States. He has been inducted into seven different Halls of Fame. He has been showered with honors and ‘best of’ distinctions by the wrestling media for decades. And he created the move called the enzuigiri, a jumping kick to the back of an opponent’s head, which is so popular that it has been used by hundreds if not thousands of wrestlers.

And even as his in-ring career slowed down, Inoki passed off his skills and experience to a new generation. Some of the wrestlers Inoki had a direct role in training include The Three Musketeers (Masahiro Chono, Shinya Hashimoto, and Keiji ‘The Great Muta’ Muto), Satoru Sayama/Tiger Mask I, Riki Choshu, Nobuhiko Takada (of UWFi fame), Hiroshi Hase, Shinsuke Nakamura, and Rocky Romero.

“What impressed me the most about Inoki was that, he wasn’t the greatest technician in the ring (due to chronic knee problems) but he was one of the smartest. He had many interests outside of wrestling, where most people in the business have none. He was involved in many great business ventures in Japan, including his own restaurants and he makes a percentage of every bottle of Tabasco sauce that enters Japan. He was a politician after retiring from the ring and still is one of Japan’s great Legends. Inoki taught me the psychology of wrestling and how to bring out my ring character, making people believe who ‘they’ think you are in the ring. Antonio Inoki is a great guy and one of my mentors who once told me that no matter where I wrestled throughout the world, New Japan Pro-Wrestling would always be my home.” – Bad News Allen Coage

But Inoki was determined to make his name larger than wrestling… and he did. In 1989, Inoki entered the world of politics. He was elected to Japan’s House of Councillors under his own party, called the Sports and Peace Party. Inoki had long been a champion of peaceful resolution (ironic, given the business from which he came) and his main goal in this regard was to try and mend fences with North Korea. Inoki managed to successfully host a joint NJPW/WCW wrestling show in North Korea in an attempt to soften the long-strained relations between North Korea and Japan. Incidentally, that show featured the one and only time that Inoki wrestled Ric Flair, in front of an alleged 190,000 people, the largest venue in wrestling history. That tenure reached its nadir in 1993 when Inoki was publicly accused of misappropriating funds, and Inoki’s response was to try and ‘work’ everyone as if this were a wrestling angle. Clearly Vince McMahon wasn’t the only promoter that embraced that approach when dealing with the media. But it didn’t work in Inoki’s case; many people saw Inoki and New Japan as one entity so whatever happened to the former affected the latter. New Japan suffered a major image tarnishing not unlike the steroid trial that devastated WWF/E around the same period.

Antonio Inoki and Riki Choshu at a NJPW press conference on March 20, 1991, to promote an upcoming Tokyo Dome show. Photo by Mike Lano, WReaLano@aol.com

As a businessman, Inoki was as shrewd and calculated as they came. He saw money in working with other companies and looked at ways to maximize fan interest when stories were reaching their end. He formed working relationships with both WWF/E and WCW at different points and with smaller local companies as well. This was done to offset the lack of NWA wrestlers available to him since those guys worked for rival All Japan. But even without the fabled names from the NWA, Inoki’s New Japan was able to thrive for decades. So much so that NJPW was able to run annual shows in the Tokyo Dome starting in 1992.

But as the 1990s progressed, Inoki’s creativity peaked and then slipped away. He struck gold at first with his take on All Japan’s ‘outside invaders’ concept. With his NJPW guys at the top of the world, Inoki decided to take Takada’s struggling UWFi and make it into something that New Japan hadn’t seen before. Inoki booked the UWFi invaders to beat his top New Japan guys at their biggest shows which led to widespread shock (and intrigue). And then it led to incredible financial success as well. NJPW’s Tokyo Dome show on April 29, 1996, which was main-evented by Takada (UWFi) vs. Hashimoto (NJPW) made a record $US 5.7 million, without any PPV or major television deals. That record has long since been broken, but at the time it was ample proof of the power New Japan had with Inoki at the helm.

And yet, that was the peak and then came the regression. After the NJPW vs. UWFi storyline concluded, Inoki had to figure out where to go next. Unfortunately, his next idea ended up being disastrous for New Japan and for pro wrestling in general.

Inoki’s next handpicked protégé was a former Olympic silver medalist in judo named Naoya Ogawa. Inoki saw Ogawa as his perfect pupil since he had the legitimate credentials Inoki loved and would live up to New Japan’s reputation as ‘King of Sports’. However, Ogawa’s push to the top came at the expense of New Japan’s ace Shinya Hashimoto. On January 4, 1999, the match between Ogawa and Hashimoto turned into a fight. Details remain murky to this day (and will likely never be fully explained now that Inoki has passed and the rumors at the time implied that Inoki ordered Ogawa to shoot on Hashimoto without Hashimoto knowing). But what is certain is that Hashimoto’s reputation was shattered beyond repair. His carefully-cultured status as New Japan’s ace, toughest wrestler, and New Japan’s stalwart defender against all outsiders, was no more.

From that moment on, New Japan began a downward decline brought on by the onset of what has become known as ‘Inokism’. It was Inoki’s personal project of mixing wrestling with MMA. MMA fighters would come to New Japan to compete against his top wrestlers (in bad matches), and his wrestlers would be sent off to fight in MMA matches (despite being untrained/undertrained). The results were as expected: NJPW’s top stars suffered from bad booking and worse matches. Somehow, Inoki thought that this was all great stuff and ignored pleas from his wrestlers to stop the madness. As the 1990s turned into the 2000s, Inokism continued and caused more and more problems for everyone arounds Inoki but not Inoki himself. Hashimoto, once his biggest star and top draw, left New Japan and formed his own company, Pro-Wrestling Zero1. Masahiro Chono wrestled far less and began to pursue non-wrestling ventures. Keiji Muto spent a year working big cross-promotional matches with All Japan and then defected there for good because he was tired of Inoki’s nonsense. So by 2002, all three of NJPW’s biggest stars from the prior decade were nowhere to be found because their boss couldn’t stop himself from going down his chosen path.

Antonio Inoki bows to Hard Boiled Haggerty at the Cauliflower Alley Club reunion in Las Vegas in February 2001. Photo by Greg Oliver

But it only got worse. Yuji Nagata had the unfortunate task of carrying NJPW on his back as world champion while trying to survive getting destroyed in under a minute in MMA fights against Mirco Cro Cop and Fedor Emilianenko. Inoki brought Joanie ‘Chyna’ Lauer to New Japan and booked her to compete against men in what can only be described as underwhelming matches. Not even Jushin Liger was protected from Inokism as he had to tow the company line and compete in an MMA match against Minoru Suzuki in 2002… despite being completely untrained.

Inoki kept trying to capitalize on the MMA boom sweeping Japan, but that’s not what his fans yearned for. They wanted wrestling, not fighting. And so, attendance dwindled, revenue dropped, and New Japan started making headlines and records, albeit for all the wrong reasons. One of their Tokyo Dome shows drew the lowest the venue’s history, despite setting the opposite record less than a full ten years earlier. Wrestling fans were far more interested in seeing Pro Wrestling NOAH show classic wrestling, Muto reviving All Japan, or even WWE as that company started making better inroads into the Japanese market. Things got so bad for Inoki that, eventually, his stubbornness would be his downfall.

In 2005, Inoki’s 51.5% majority stock in NJPW was bought by video game company Yuke’s. This effectively ended Inoki’s 33-year tenure as owner of New Japan, but Inoki still intended on having an impact on wrestling. He founded the Inoki Genome Federation (IGF) and enjoyed one last hurrah in wrestling by showcasing, among other things, the last-ever singles match between Brock Lesnar and Kurt Angle for the IGF Championship (which was actually NJPW’s IWGP Heavyweight Championship belt that Lesnar had won and hadn’t relinquished). Inoki tried to maintain positive momentum and capture the same fanfare as in decades past but to no avail. IGF became just another entity that tried to latch onto MMA’s popularity but struck out. It didn’t have the same wildness of K-1 or PRIDE and other wrestling companies did a better job of it anyway, including in New Japan. Even after Inoki’s departure, New Japan still continued with Inokism for several years, albeit in small doses. It wasn’t until Wrestle Kingdom 9 in 2015 that the last vestiges of Inokism died, when Minoru Suzuki – now a full-time wrestler – competed against Kazushi ‘The Gracie Hunter’ Sakuraba in a wrestling match. Though it was more worked than those of the past, Inoki’s original ideas were still there to be found in this spiritual last hurrah of his.

After Inoki retired from politics following a second term from 2013 to 2019 and he faded from public view, much of the conversation turned towards his legacy and the stories of his life. He brought South Ossetian wrestler Victor Zangiev to wrestle for New Japan and the result was so impressive that video game company Capcom created the Street Fighter Zangief (Red Cyclone) after Zangiev. He appeared in many Japanese commercials throughout the decades.

Inoki bought an island from Fidel Castro thinking there was buried treasure on it and named it ‘Friendship Island’. His close relationship with North Korea (owing to it being Rikidozan’s birthplace) led to that country publishing a stamp bearing Inoki’s likeness. He appeared to be one of the few Japanese people of any kind or profession to be treated warmly (or at the very least, cordially) by North Korean officials. He even made his trademark slap to the face such an integral part of wrestling culture that wrestling fans in Japan lined up to get slapped.

Inoki’s legacy will be a dual one. On one hand, his positive influence on pro wrestling cannot be denied. He created and ran New Japan for over three decades and changed the business in a major way. He went in a more realistic direction and had room on his cards for smaller and more technically-gifted wrestlers. Many of the top in-ring performers of the past four decades – from Bret Hart to Eddy Guerrero to Bryan Danielson to AJ Styles – all got to work in New Japan and show what they could do. Inoki gave plenty of time to cruiserweights in particular with Tiger Mask I and Dynamite Kid in the 1980s and later an entire generation of cruiserweights like Jushin Liger, Chris Benoit, Ultimo Dragón, and many others. He popularized the outside invader’s angle, which Eric Bischoff later repurposed with the New World Order. And Inoki took wrestling in a more realistic direction, to the point that some matches looked almost indistinguishable from actual amateur wrestling bouts or MMA fights.

At the same time, Inoki, like any promoter, was prone to making mistakes and not fixing them soon enough. Though he left wrestling for politics in the early 1990s, he couldn’t abandon the habits and mentalities he adopted as a promoter. His carny-like response to a public scandal damaged New Japan’s reputation. He refused to accept that he was going in a wrong direction and stuck to his Inokism philosophy while drowning out all the valid criticism being screamed at him from every direction. In the end, it took him losing his majority stock in the company for him to finally be ousted from the very company he founded. Inoki’s departure was absolutely necessary; by 2004 the company was at its lowest point ever and was far behind NOAH and All Japan in terms of far interest. There were even discussions of the company going bankrupt so long as Inoki remained in charge.

Though New Japan turned around eventually in terms of quality, the company has yet to reach the same gates or financial prowess as it had during the 1990s before Inoki decided that MMA was the future. And while New Japan’s still thriving today, wrestling-wise it doesn’t resemble Inoki’s original approach as much. Under Gedo’s booking and with the wrestling styles of such masters as Hiroshi Tanahashi, Kazuchika Okada, and others, modern New Japan’s neo-Strong Style resembles 1990s All Japan more closely than it does 1990s New Japan Strong Style.

And yet, Inoki still managed to achieve something special: he became larger than life. He was such a curious personality in life (married four times, with one daughter, Hiroko) that he’ll likely still have an impact on wrestling (and Japanese politics) long after his death. And even with Antonio/Kanji/Muhammad Hussain Inoki gone (he secretly converted to Islam in 1990), his name will live on in wrestling as his son-in-law Simon Inoki looks to bring pro-wrestling to China, where the sport has yet to take off.

But if Simon sees even a fraction of his father-in-law’s success, then he count himself a very happy man.

TOP PHOTO: Antonio Inoki in the ring at New York City’s Madison Square Garden during a WWWF event. Photo by John Arezzi

MORE INOKI STORIES

- Sep. 30, 2022: Wrestling legend Antonio Inoki passes away

- May 20, 2021: ‘Dark Side of the Ring’ sells the sizzle on Collision in Korea

- June 4, 2016: Wrestling world remembers Muhammad Ali

- Mar. 28, 2010: WWE Hall of Fame ceremony a serious event

- Mar. 17, 2010: Hansen, WWE salute Inoki’s courage, innovations

- Nov. 26, 2008: Savage, Orndroff, Graham top 2009 PWHF induction list

- July 16, 2005: Tragos/Thesz Hall inducts six more