Richard Wilson, known as The Renegade in World Championship Wrestling, died by suicide on February 23, 1999.

But the life went out of him long before that.

For it is not enough to trace Wilson’s death at 34 to performance-enhancing drug abuse, declining physique and a loss of his WCW contract. The seeds of his depression were planted in childhood and grew nonstop, though he never almost never let it known beyond a circle of a few choice friends.

Wilson’s mother was emotionally unavailable, recalls his ex-wife Kimberly Tilton. His father was out of his life, behind bars for his involvement in a fatal car accident. His stepfather beat him. Wilson’s high school football coach from Columbus, Georgia, who asked that his name not be used, recalled encountering him one morning as the student hid his face with his hand.

“I pulled his hand out of the way and I saw what it was, his cheek was red, black and blue. And so, I said, ‘Okay.’ I said, ‘Go get in the truck. Go get in my truck,’ and he did, and I took him to his house, and we got his clothes,” the coach said. Wilson ended up living with a minister’s family in Florida, later returning to Columbus only to crash on coaches and sleep on beds in friends’ houses.

And those were the roots of the man that Hulk Hogan and Randy Savage identified as the incarnation of the Ultimate Warrior.

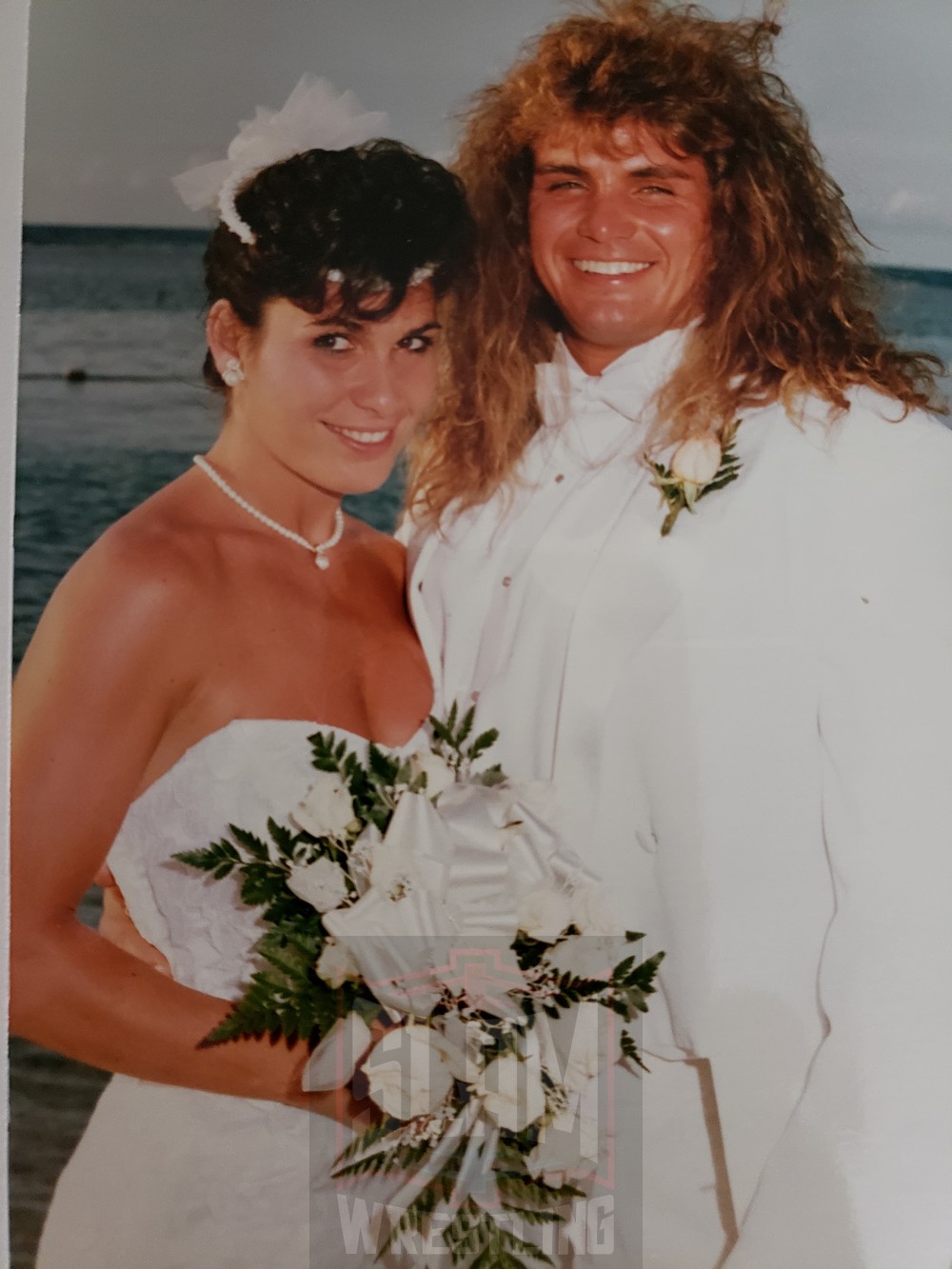

Kimberly Tilton and Richard Wilson. Photo courtesy Kimberly Tilton

HITTING THE IRON

Though circumstances forced Wilson into a near-nomadic life as a teenager, Richard Hammock, a childhood friend with whom he stayed, remembers bonding over bodybuilding, training six days a week together. It didn’t leave much time for school work, which Wilson did, but just enough of it to get by. He cared more about sports, becoming an impressive athlete in high school by playing football as a defensive end. He also excelled in gymnastics.

“He was unbelievable at gymnastics,” his former football coach says. “He used to get out there with the gymnastics girls when we went to football practice and do everything they could do and just as good as they could do it. He was good at it. I’m going to tell you, he was really, really, really good at it. I’ve never seen anybody close to him.”

The problem for athletes like Wilson and Hammock was that there weren’t a lot of places to work out, just Oates Gym, run by pro wrestlers Jerry and Ted Oates.

“Columbus is huge now. They’ve got seven, eight, nine different gyms now. But back then that was the only one. And it was just a hole in the wall,” Hammock says. “And it didn’t have heating or air conditioning or nothing. And it was just the weights like in a storage room. It was brutal, in the winter and summer, trust me. Like, there ain’t no way I would even attempt to do it now.”

In the 1970s, Jerry Oates won a number of tag team championships in the National Wrestling Alliance with partners such as Mike George, Jesse Ventura, Ron Garvin and his brother, Ted Oates; he held tag titles in Asia, as well as the NWA Central States Heavyweight Championship and the NWA Pacific Northwest Heavyweight title. Fans still vividly remember him from Superstation WTBS, which aired Georgia Championship Wrestling.

”When I came off the road full time, guys knew I was back home and I was still wrestling here for the Georgia wrestling office, my brother and I, and then the gym started growing, getting bigger and bigger,” says Jerry Oates.

Wilson observed Oates’ training process and decided that he wanted to be a pro wrestler.

“[Wilson] was a big, strong, good-looking kid. So, I was going to train a couple of [other individuals] and he said, ‘Man, I want do this.’ I said, ‘You guys better be sure you want to do this now.’ Because I didn’t do it for free, even back then, because it’s a lot of work, so [Wilson] wanted to do it and so I figured, well, he is a big, good-looking kid,” Oates recalls.

In addition to wrestling, Wilson had another fledgling career. He began dancing professionally in a Chippendales-like show called Ultimate Fantasy, flaunting his physique for paying customers, and going by the name “Rio, Lord of the Jungle.” In 1987, Eric Henderson, the owner of the group, discovered him at a beach in Panama City, Florida. Soon Wilson and Henderson were roommates as they traveled all over the United States and Canada.

“[Wilson] and I got along great. He had a very blunt way of saying things, and it was how he felt and whatever. And if you listen to what he said instead of how he said it, you’d be fine,” Henderson explains. “And he rubbed a lot of people wrong and that’s why he was my roommate. I didn’t have any issues with him. He was a damn good guy.”

Henderson paid Wilson $125 a show, but that wasn’t his only source of income when working for Ultimate Fantasy. Wilson made about $400 to $500 each night in tips. The group was so successful that Chippendales picked up Ultimate Fantasy as a roadshow.

Richard Wilson and Eric Henderson. Photo courtesy Eric Henderson

Back in Georgia, Oates trained Wilson, maybe once a week for four months, but his focus was still on dancing.

“He was a cocky kid because he was a good-looking kid,” Oates continues. “And so, I started training him and I trained him on Saturdays. So, Ricky was dancing … and he’d be gone a lot, and what he did, he thought he knew more than he knew.”

The dancing gig had other perks, such as in 1988 when he met Tilton in Boston where she was competing in a fitness contest.

“He was in a Chippendale-type dance group and he had seen me in the contest. And I had a friend that he knew and he wanted to meet me.”

Richard Wilson, front and center, at an Ultimate Fantasy show. Photo courtesy Eric Henderson

Unlike the arrogance that he displayed with Oates, Wilson acted respectful around Tilton.

“He was very quiet, very shy, very reserved,” Tilton remembers. “He was from Georgia, so very Southern gentleman. … Just a really heavy Southern accent, but always wore leopard pants, like rock-and-roll pants, long hair, but very, very soft-spoken. Did not drink, did not do any drugs, worked out, ate right. I think that’s why he was interested in me, because I worked out also.”

Wilson had moved to Boston to train with the legendary Walter “Killer” Kowalski, though, he never trained Wilson. Instead, one of Kowalski’s first students, Richard Byrne, continued Wilson’s in-ring education. “Superstar” Richard Byrne, as he was billed, wrestled mostly for New England independent promotions, achieving only moderate fame in the squared circle.

Kimberly Tilton and Richard Wilson. Photo courtesy Kimberly Tilton

FIRST BREAK

While Wilson didn’t train with Kowalski, he did work for Kowalski’s International Wrestling Federation, where he often wrestled against more experienced grapplers, such as his regular opponent, Vince Apollo. But Wendell Robinson, stage name Wendell Weatherbee, a former Kowalski student and occasional New England promoter, ended up having arguably the biggest impact on Wilson’s career. Robinson ran a few shows in the early 1980s, but took a decade-long break before resuming the job with events in Maine, Vermont, and Burlington.

When Robinson first caught a glimpse of Wilson, he was impressed. Like Jerry Oates, Robinson thought that he had the perfect look.

“He was working for Richard Byrne, just on the show, mid cut, opening match, but when I saw him, what he looked like, I saw his body and I said, ‘Wow, I’m going to move him up, put him up higher on my show,’” Robinson remembers. “I teamed him up, put him with Ax of Demolition or someone similar just to put him higher up so he could get moved up the ladder a little bit.”

Robinson ran All-Star Wrestling, where future big-name competitors such as Triple H and Perry Saturn duked it out with seasoned in-ring generals like Ray “Hercules” Hernandez, Nikolai Volkoff, Mike Sharpe, and Jimmy Snuka. He was also able to land a recent free agent and former World Wrestling Federation champion who wasn’t known to make appearances on the independent scene. That free agent was The Ultimate Warrior.

Richard Wilson as “Rio, Lord of the Jungle,” tangles with Superfly Snuka on a show in Billerica, Massachusetts. Photo courtesy Rich Palladino

Robinson drove limousines for top WWF stars around New England for four or five years.

An encounter with a WWF newcomer changed Robinson’s life.

“So, what happened is Warrior just got there. He was on the ‘C’ cards. He was just working with Hercules off TV at high school gyms,” Robinson continues. “And I told him that he was going to be a future world champion. Then he got the Intercontinental belt and the next thing you know, I’m driving him. We became friends. I took care of his house in Arizona, 6,000 square-foot home. I was living in his house while he was traveling around the country, handling all his business.”

That friendship enabled Robinson to book The Ultimate Warrior on his shows, some of which also showcased Wilson. That’s when the connection between Wilson and The Ultimate Warrior began, a connection that would haunt Wilson even after he died.

Robinson saw star potential in Wilson and wanted him on his shows, regardless of his other career. “Sometimes [Wilson] had a hard time working Friday or Saturday nights because in wrestling, they don’t make any money and he could make more dancing,” Robinson remembers. “And I said, ‘Listen, just be on my show and I’ll pay you extra.’ And I did pay him a little bit more than some of the other guys at that particular time.”

While dividing his time between dancing and wrestling, Wilson took up yet another vocation. Ring announcer Rich Palladino met Wilson at the Woburn Mall in Woburn, Massachusetts, where Palladino worked at a CVS Pharmacy and Wilson worked at General Nutrition Center.

People put two and two together like, ‘Oh, this guy at GNC is a wrestler and the guy at CVS is a ring announcer,’” Palladino recalls. “So, we just ended up connecting, just literally walking by each other’s store. And we would just shoot the sh*t and whatever, and that was it. So, from there, it would be every time I was working, I’d go down and say hi if he was working and vice versa.”

Palladino recalls that Wilson fit the part of the average GNC customer.

“He had this long, teased-out, flowing hair, working at GNC, everybody there wore the Zubaz pants and the stringy tank tops, and that was him, he fit the role perfectly,” Palladino says.

Although Wilson’s personality could come off as cocky, Palladino never saw that side of him. “I found him very, very open and easy to talk to. I mean, for a couple of mall buddies anyways. Like I said, we weren’t best friends or anything, but we had a mutual liking for each other, I think because of the common bond of wrestling. He was very chill, very relaxed, just a nice, easygoing guy.”

Richard Wilson as “Rio, Lord of the Jungle,” on a show in Billerica, Massachusetts. Photo courtesy Rich Palladino

JAPAN BECKONS

In March 1993, Wilson was invited on a tour of Japan with Genichiro Tenryu’s Wrestle Association R promotion, where he wrestled John Tenta on two occasions. He also teamed with El Samurai to defeat Ultimo Dragon and Nobukazu Hirai.

“[Wilson] liked it, but he didn’t like that they wrestled early in the morning,” his high-school coach says. “He liked the money because they paid him good.”

While the tour of Japan was a financial success, the travel strained his relationship with Tilton. Though they married in 1992, their conflicting schedules caused them to grow apart.

“He started going to Japan and then I started traveling with work and we just kind of, you know, you have to be together to be married,” Tilton says. “We just grew apart. We tried to fight it for the longest time, but we just became like friends. There just wasn’t any romance, intimacy, nothing. It was just like he was living his life. I was living mine.”

Kimberly Tilton and Richard Wilson. Photo courtesy Kimberly Tilton

One moment particularly stands out to Tilton.

“I remember getting a bouquet of flowers [from Wilson] when I was on the road and it said, ‘To my best friend, Happy Anniversary,’” Tilton says. “And I remember looking at my best friend, true friend, and saying, ‘This feels weird.’”

Wilson returned to the United States in March 1993 to work two shows for All-Star Wrestling. He competed against Vince Apollo for the first event, then teamed with Demolition Ax to defeat Nailz and Apollo. But, in April, he was back in Japan to compete in WAR where he faced his usual opponents like Tenta, along with some new faces like Yuji Yasuraoka, King Haku, and The Great Kabuki.

Although Wilson was only working in WAR and on the New England independent scene, he caught the attention of the World Wrestling Federation. At an August 18 taping of WWF Challenge, Wilson wrestled a try-out match against The Brooklyn Brawler (Steve Lombardi). Although The Wrestling Observer reported that Wilson looked decent, WWF never offered him a contract.

Richard Wilson in a WWF tryout match against The Brooklyn Brawler in Lowell, MA. Photo courtesy Rich Palladino

WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP WRESTLING

As Wilson continued on his path, working for the likes of Connecticut’s Galaxy Wrestling Federation and WAR, WCW was in the process of overhauling its product. Hulk Hogan, one of the biggest names ever in pro wrestling, had signed a deal with Ted Turner’s company in 1994. In an attempt to boost the ratings of the WCW’s television shows, Hogan wanted to return to the prime of Hulkamania and surround himself with some of the pieces that made him a megastar, such as The Ultimate Warrior and Andre the Giant.

The problem was that Andre died in 1993 and no one in WCW wanted to deal with The Ultimate Warrior, who was notorious for his poor attitude. WCW sought out replacement wrestlers for the two megastars. An agile, seven-foot college basketball player with no wrestling experienced named Paul Wight filled in for Andre. He did well for himself as The Giant and then the Big Show.

Hogan and his team swung and missed on using “Jungle” Jim Steele, another hot body with limited on-mar skills as a Warrior knockoff.

The Renegade in WCW.

Manager Jimmy Hart, then working for WCW, found an answer and had Wendell Robinson to thank. Robinson mentioned Wilson during a phone conversation with Hart, who asked to see a promo picture of Wilson and video of him wrestling. The tape he sent contained a match of Wilson’s from a show that also included an Ultimate Warrior appearance. It highlighted Wilson’s uncanny resemblance to the former WWF champion.

“When you see them in the same place together, you’d almost die,” Robinson explains. “And Jimmy Hart couldn’t even believe it. So, he ran over to Hulk and that’s how they got excited about bringing him in.”

Wilson was finally important. He had found his spotlight.

On WCW Prime, which aired before that night’s WCW Uncensored pay-per-view, Hogan introduced the WCW audience to The Renegade in a room clouded with fog. It was meant to represent, as Hogan put it, “the dark side.”

In the storyline, Jimmy Hart, then the manager of Hogan, vanished. The main suspect of the purported kidnapping and assault was Vader. Desperate and fuming, Hogan called on The Renegade, whom he described as “the most powerful man” he had ever met. He also made it clear that this was not The Ultimate Warrior. This was something better.

Just behind Hogan, surrounded by smoke, was the massive, shadowy frame of Wilson. Hogan explained that there were men like this all over the dark side, but that The Renegade was the strongest one of them all. These men, and The Renegade in particular, had powers that no ordinary man could possess.

That night, Hogan’s group claimed victory over all of their ruthless adversaries. The Renegade protected Hogan, who defeated Vader in a strap match. Jimmy Hart appeared at ringside, escaping from the clutches of Ric Flair, Vader, and Arn Anderson. All was well on Hogan’s team.

It was a great introduction to Wilson, but it was marred by its cartoonish nature and an illogical finish that saw Hogan beat Flair, even though Vader was his actual opponent.

There were other problems. The Ultimate Warrior was slightly upset that Robinson sent the tape of Wilson to Jimmy Hart. He also was unhappy that Wilson was using the same airbrush artist for his clothes that he used for his wardrobe.

“When I was living in his house, I was dealing with his airbrush artist, which is the same guy who did the airbrushing for Jimmy Hart, and I believe the Nasty Boys,” Robinson says. “Jimmy Hart turned everyone on. So, when the Warrior was having his clothes airbrushed, he ended airbrushing stuff for Renegade. It wasn’t my idea.”

Robinson tried to calm The Ultimate Warrior, who was upset about Wilson and the similarity to his character. “I told him, ‘Are you out of your mind? I know what I’m doing.’ I said, ‘You should hope he takes off, because everyone that sees him is going to be thinking about the original,’” Robinson explains. “That’s how I looked at it. So, I think he was a tad bit bothered, although he wasn’t bothered when he was at my show. He didn’t say anything like that to me then.”

While Wilson was working a high-profile angle, WCW was only paying him $500 a night.

Adding to the stress, fans and other wrestlers weren’t embracing the newcomer because The Renegade symbolized the worst critiques of WCW.

After Hogan signed with the company, many former WWF wrestlers jumped shipped to WCW and received massive attention. While The Renegade was never part of the WWF, he was still an unlikable character, since he wasn’t seen as being on the level of WCW’s undercard. The backbone of the company, like Brian Pillman and Steven Regal, who had paid their dues in the eyes of the fans, were shoved aside to make way for the incoming talent.

“Stunning” Steve Austin was one of those men in the locker room who disagreed with the booking decisions. In September of 1994, Austin lost the WCW U.S. title to “Hacksaw” Jim Duggan, who had only entered the company a month prior.

So, asked to lose to The Renegade, Austin refused.

In a similar scenario to Austin-Duggan, The Renegade won the WCW World Television Championship from Arn Anderson at The Great American Bash 1995. Title defenses followed, but mostly against enhancement talent in matches that ended within a minute or two.

FALL FROM GRACE

There were exceptions. Wilson successfully defended the title against Paul Orndorff and Arn Anderson, but The Renegade just wasn’t catching on.

Neither the critics nor the fans were impressed with Wilson. He looked the part, but his similarities to The Ultimate Warrior were a detriment. The Ultimate Warrior was seen as lazy, goofy, and difficult to work with. Wilson was also considered guilty of all these transgressions by association.

WCW booked Wilson’s matches purposely short to hide his flaws, but the fans could see that the emperor wasn’t wearing any clothes. He had been exposed.

“I think he looked a little uncomfortable,” Robinson says. “Honestly, I thought he did better when he worked on my shows. I don’t think I would’ve hired him the way I saw him looking at WCW. I wouldn’t have been interested.”

“[Wilson’s wrestling ability was] very basic. I think they just wanted somebody to look like Warrior, and tried to recreate it, and the fans hated it and it didn’t last long obviously,” Palladino says. “But would I say, four-and-a-half, five-star matches? No. I would say three star, two-and-a-half, three stars. He was a power wrestler. He was just literally running to the ring like Warrior.”

Although Wilson and Tilton were drifting apart, they remained friendly. One night, they found out that they were staying at the same hotel in Atlanta. Tilton and her friends decided to stop by the hotel’s bar, where many of the wrestlers were relaxing after an event.

“[One of the wrestlers] said to me that they were going to use [Wilson] and throw him away,” Tilton recalls. “When I went up to the hotel room that night to see him, he was in so much pain. He had been hurt from falling and landing. And then they gave him prescription pain medicine, and then they’re drinking on the road.”

Meanwhile, Kowalski wanted to distance himself from Wilson. He made it a point to tell wrestling-news outlets like The Wrestling Observer that he never had a part in training him. Although the statement was true, it made Wilson out to be a plague. No one wanted to come close to him. They feared that his reputation would infect their careers and reputations as well.

On the November 6, 1995 episode of WCW Nitro, emanating from Jacksonville, Florida, Wilson’s involvement in the Hogan storyline ended with a match against “The Taskmaster” Kevin Sullivan. Wilson dashed into the ring, colliding with Sullivan and landing three clotheslines that sent The Taskmaster to the outside.

On the floor, Wilson focused on Jimmy Hart, who had turned against Wilson and aligned himself with Sullivan. The distraction was enough for The Taskmaster to take advantage. Wilson briefly regained control, executing a powerslam and a handspring elbow, but Sullivan came back with a double-foot stomp off the top rope. Sullivan pinned Wilson.

It wasn’t over. Hart grabbed a cup of water and splashed it in Wilson’s face then wiped off his face paint. “You’re just plain old Rick,” Hart screamed at Wilson. “You’re nobody. You’re nothing.”

Commentator Bobby Heenan remarked, “He just destroyed that man’s identity.”

WCW publicly humiliated him. They did more than just wash the paint off of Wilson’s face, they also washed their hands clean of Wilson.

“If you go look back at some of the film of Ricky on YouTube, when he’s wrestling in WCW as ‘Renegade,’ you’ll see when they pulled his face paint off. You’ll see that they said, ‘You’re not The Renegade. You’re not The Renegade. You’re not anything. You’re just old Ricky,’” his high-school coach says. “That’s what broke him.”

Richard Wilson and Kimberly Tilton. Photo courtesy Kimberly Tilton

DESCENT

The fragility of Wilson’s self-esteem drove him to change his lifestyle, but it wasn’t for the better. Tilton recalls her ex-husband as a moderate drinker until his WCW years. “Two strawberry wine coolers and that was ‘whew,’ the whole evening.” she says. “He just didn’t drink. Later on, as our relationship was falling apart, we had gone to Panama City one New Year’s and he was slamming them back.”

Henderson once visited Wilson at a Monday Nitro when it ran Club La Vela in Panama City, Florida. He also noticed a change in his alcohol consumption.

“And then [after Monday Nitro], we went into the club, after he changed clothes, he came in, he and I just did these purple Hooters shots,” Henderson remembers. “Every time we’d drink one, we’d put the cap, it was a plastic shot glass, upside down. And we probably had 40 of those damn things up on the bar. I should have known better than to do it. You know, I was maybe a buck-90 and I’m 5’11” and I was in great shape, but I couldn’t do that many. And I went home and peed my, sh*t my pants, and that was that, but he was fine.”

And a drug called Gamma-Hydroxybutyric Acid (GHB), a depressant, began to play a role in his life.

“At the time when Ricky started on it, you could go into a GNC store and buy it anywhere. It was a health-food supplement,” his high-school coach says. “And then they found out the truth about it. It is the biggest depressant on the face of this earth.”

Renegade, Jimmy Hart and Joe Gomez.

Joe Gomez, a former WCW wrestler who tagged with Wilson, met him in the mid-1980s when Gomez was working as a bouncer for a bar called Confetti in Tampa, Florida. Confetti occasionally ran special nights with male dancers, which sometimes featured Wilson. After years without having contact with each other, they reunited in 1996 when Gomez joined WCW.

He remembers Wilson and others wrestlers scooping up bar after bar of GHB for $5 a pop.

While some wrestlers were using it as a recreational drug, Wilson, at least at the beginning, took it to get and stay in shape.

“Ricky was training and that was supposedly a main draw of [taking GHB], to get you deeper out of sleep and build muscle growth,” Gomez remembers.

Wilson found his career in a downward spiral. One month he was defending the WCW World Television Championship against Paul Orndorff. The next month, he was losing the title to Diamond Dallas Page at Fall Brawl 1995.

By this time, The Renegade was the exemplification of WCW’s mismanagement and creative incompetence. Fans stood by helplessly, watching the last remnants of the promotion built on the hard work of Ric Flair and Dusty Rhodes crumble under the weight of wrestlers saddled with childish gimmicks and storylines. The Renegade became the mascot of WCW’s inability to connect to the modern fans.

Meanwhile, Steele, WCW’s original Warrior replacement, showed up in Philadelphia’s Extreme Championship Wrestling, which catered to alienated fans. ECWs owner, Paul Heyman, made his promotion the antithesis of big-budget projects like WCW and The Renegade.

At an ECW event on June 27, 1995, Heyman accompanied a massive wrestler named 911 to the ring to battle Steele, who had been released from the company after languishing as an opening act for over a year. After 911 chokeslammed Steele into unconsciousness, Heyman grabbed the microphone and taunted him, “To your brother-in-crime, that stupid, goofy Renegade, who can’t even imitate a decent gimmick, up and down you go, na na na, goodbye.”

The crowd roared in agreement.

The Renegade had no fans in the industry. The causal WCW audience never took to him and wrestling’s die-hards couldn’t get behind his poor performances and his immediate push up the ladder. Heyman sacrificed Steele and The Renegade to further enhance his own anti-establishment image. That’s what made ECW cool. But Steele and The Renegade weren’t cool. They never were. To the wrestling fans and critics, they were just corporate tools.

Then Wilson was voted “Worst Wrestler of the Year” by the subscribers of The Wrestling Observer. His failure was firmly established.

For the remainder of his WCW career, Wilson played the part of a punching bag for established wrestlers such as Brian Pillman, The Giant, and Lex Luger. Some of these matches didn’t even air. If he did have a match on Monday Nitro, it was often the dark match.

Wilson was becoming less and less consequential to the WCW product. He needed to feel important. He needed to impress. But he was losing his opportunity to do so.

“It’s a big fall, when someone brings you in and wants to put you at that level and then robs you of it,” Robinson says. “If they brought him in and gave him a job and he had a chance to work his way up, that’s different. But when it fails, where do you go from there? No way but down.”

“I think he got too much of a push too fast, obviously,” Gomez says. “Nobody could have gotten that kind of monstrous push and gotten over on Arn Anderson and Paul Orndorff, two of the all-time greats, and not had a good match. So, without any follow up on that, there’s no way you’re going to get over.”

Wilson was occasionally placed into a storyline. However, the paint was gone. The singlet was gone. And his physique was shrinking. He became part of a short-lived stable of WCW’s young hunks called The In-Crowd, that included Wilson, Alex Wright, Jim Powers and Joe Gomez. A short video of them walking around a beach without shirts on aired on WCW Nitro in 1996.

“Oh, it was horrible,” Gomez remarks.

It didn’t last long and it didn’t stop his stock in WCW from falling. On a June edition of Monday Nitro, The In-Crowd won a bout against Dungeon of Doom’s Braun the Leprechaun, Hugh Morrus, Kevin Sullivan and The Barbarian. However, they won by DQ when The Giant came out and chokeslammed all of The In-Crowd. Wilson’s team won, but only because an illegal participant beat them up.

Wilson knew he couldn’t wrestle at the rate that the others could. His appearance was his only selling point.

He had cycled off of steroids to avoid jeopardizing his employment, but now he needed to regain his muscular definition to keep his job.

That meant that he needed to go back on steroids, but doing so would only result in him failing more drug tests and receiving more suspensions. It was becoming apparent that he had no way to return to the spotlight.

In 1996, Wilson and Gomez formed a tag team that competed mostly on shows such as WCW Pro and WCW Saturday Night. Jimmy Hart, who was in charge of mid-level talent, tried to come up with any idea that could keep Wilson and Gomez on television. The problem was that Hart was in charge of how the talent was used, but not in charge of which wrestlers were used.

“Jimmy tried his best,” Gomez says. “God bless him, he really did.”

While Wilson and Gomez put over tag teams such as Harlem Heat, Public Enemy, and The Amazing French Canadians, they managed to score wins against High Voltage, The Armstrongs, and makeshift teams like Sgt. Buddy Lee Parker and Sgt. Craig Pittman.

In May, Wilson turned on Gomez during a match against Hugh Morrus and Konnan. After an exhausted Gomez performed a double Japanese arm drag on both Konnan and Morrus, he fell to his knees, reaching for a tag from Wilson. Wilson withdrew his hand, jumped off the apron and walked back to the entrance. The team broke up. The Renegade finally had another storyline.

The two former In-Crowd members briefly feuded on WCW’s B shows. In one match between Meng and Joe Gomez on WCW Saturday Night, The Renegade bolted to the ring to assault his once tag-team partner. Meng, who was victorious against Gomez, then applied the Tongan death grip on Wilson, who collapsed instantly.

The Renegade wasn’t a threat to the rest of the locker room. Wilson, even during his run-in, still had to put over the stars who weren’t even involved in the storyline. Wilson and Gomez wrestled, but little attention was given to their feud.

Afterwards, Wilson floundered, losing to the likes of Bobby Blaze, Super Calo, and Van Hammer. He wasn’t a priority. He was barely an afterthought. His most high-profiled role in 1998 was when he became a body double for The Warrior, who had joined WCW to feud with Hulk Hogan. Wilson couldn’t shake the comparison to The Warrior. He never would.

Wilson was released from his WCW contract in December of 1998. Tilton believes that Wilson was set-up, as management knew that he would test positive for steroids, reason for termination. “He had to go to counseling for it. And then he got back in and then they tested him again and he failed again. And then that’s when they canceled his contracts. That’s all he wanted to do in life and then he lost it all.”

Wilson lost his one chance to be important. Getting on national television still did not allow him to outrun his childhood issues.

AFTER THE JEERING STOPPED

His high-school coach offered to help him, but Wilson wasn’t interested.

Wilson was working as a bouncer, making $60 a night while also training to be a farrier. It was a far cry from his days in WCW.

That wasn’t his only source of stress. Wilson had a new girlfriend, but their relationship was becoming increasingly toxic. Tilton alleges that Wilson and his girlfriend had picked up a habit.

“He was really into drugs with her,” Tilton says.

While GHB was sold in stores such as GNC, Wilson had begun using a variation of it called verve. While GHB is a clear liquid or a crystalline powder, verve is a purple liquid that is produced in people’s homes and was sold by individuals around Atlanta, Georgia. Verve and GHB, whose street names include scoop, goop, and liquid ecstasy, are commonly known as date-rape drugs, because of the sedative effects.

GHB slows down brain activity and induces a state of relaxation. It’s commonly used to combat anxiety and insomnia. However, it has a number of other effects. It can also cause hallucinations, euphoria, and aggressive behavior. The withdrawal symptoms include insomnia, anxiety, tremors, increased heart rate, increased blood pressure and psychotic thoughts.

Chris Benoit, who murdered his wife and child before hanging himself in June 2007, was known to abuse GHB, as was another wrestler, Chris Adams, who once overdosed on the drug, but managed to recover. A year later, Adams was shot after engaging in fight with a friend at a bar, demonstrating the irregular and hostile behavior that accompanies the use of GHB.

GHB propelled Wilson down a hole from which he’d never escape, much like Benoit and Adams.

The wedding of Kimberly Tilton and Richard Wilson. Photo courtesy Kimberly Tilton

Unlike Wilson’s latest relationship, the friendship between Tilton and Wilson, who never divorced, remained friendly and healthy. They separated, but the two stayed close, and Wilson even planned to visit her in Charlotte, North Carolina.

But he never made there.

“I talked to him on the phone a couple times and then I got divorce papers,” Tilton says, “and then two weeks later he committed suicide.”

Investigating the death, a police officer contacted the high-school coach after finding his name on a card among Wilson’s possessions.

He said, ‘Do you know a Richard Wilson?’ And I said, ‘Yes I do. Probably better than anybody on the face of this earth. … I raised him.’ He said, ‘Are you his father?’ I said, ‘No, I’m not his biological father.’ I said, ‘But I might as well be.’ He said, ‘Well,’ he said, ‘he’s committed suicide. He’s dead.’ I almost hit a car trying to get off the interstate, to pull over,” his coach remembers.

Tilton had a difficult time believing Wilson died by suicide.

“I was working in a nightclub here in Charlotte and somebody came and got me and said, ‘Do you know Rick Wilson?’ And I said, ‘Yes,’ because I thought he had come to the club because we would talk on the phone all the time. And I thought, for sure he was going to come to Charlotte,” Tilton remembers. “And they took me up in the office and one of his good friends was on the phone. And he said, ‘We remembered that you worked here.’ And they told me that he had passed away. And I thought, for sure, it was like a car accident, drinking, something like that. And then they told me no, that he had taken his own life and I couldn’t believe it. And the reason that I couldn’t believe it is my father committed suicide. So, there’s a double whammy.”

It’s impossible to pinpoint an exact reason why Wilson committed suicide. He did not leave a note.

Drugs likely played a part; verve and GHB could have influenced Wilson’s choice.

Richard Wilson and friend. Photo courtesy Eric Henderson

Eric Henderson recalls the story that he heard about the night Wilson committed suicide. Apparently, Wilson had been doing cocaine and verve over the weekend and came home. ”He told his wife or girlfriend, whatever, he wanted his verve and she hid it. And so, she called some wrestlers to come over and get him.” She knew he couldn’t handle him high on verve. Denied another high and frustrated, Wilson shot himself.

It left Wilson’s friends and family with questions, regrets, and a ceaseless pain.

“Why suicide? And what’s so bad is when you do this? I’ve said it a thousand times. Don’t you understand the people you hurt when you left us?” his coach says. “He just doesn’t understand. And then I prayed for him, that God would let him into heaven so I could see him again.”

Wilson’s funeral was understandably distressing. No one from the wrestling industry came. Wilson didn’t have many close friends. Childhood friend Mike Curevich, who had a brief career as a wrestler, showed up, as did some acquaintances from Wilson’s days as a dancer.

“I remember [Wilson] looked nothing like the person that I knew and I mean, nothing,” Tilton says. “He was dressed in a pair of overalls [in the coffin] and his hair was falling out. It was all thin. He was so small. I was shocked, absolutely shocked.”

Wilson’s girlfriend attended the funeral, but she wasn’t ready for it.

“You have to look at it a little bit from his girlfriend’s side, she’s in shock. That’s a horrible thing to have happen. She had been working at [a gentleman’s club called] Gold Club in Atlanta, I think,” Tilton says. “And so all that she had in her car to put on for clean clothes were high heels, and a dress, but she came to the funeral like that. And she was whacked out of her mind. I don’t know if it was prescribed. I don’t know if she’d been drinking, but Rick’s mother was not happy.”

A person’s personality can sometimes change depending on whom the individual allows to see it. Wilson hid himself from various people.

“He was just a really good dude,” Gomez says. “He loved the business.”

His high-school coach remembers a moment that sums up his opinion of Wilson.

“Nobody could say anything bad about that kid because he just liked to help people. He was not an asshole, not at all. In no way shape or, form. He was nice,” his coach recalls.

“Matter of fact, a little girl come up to us at the Atlanta Braves stadium one night when he and I were there, and she asked him, ‘The people you wrestle, are y’all friends?’ And he looked at her and he said, ‘I wouldn’t wrestle nobody that wasn’t my friend. I might get hurt.’ He was not kidding. He was not joking. He was telling her the truth. But he was just so nice to her, and she was just somebody who walked up. But that’s the way he was.”

— Special thanks to Richard Lannon and New England Pro Wrestling Classics