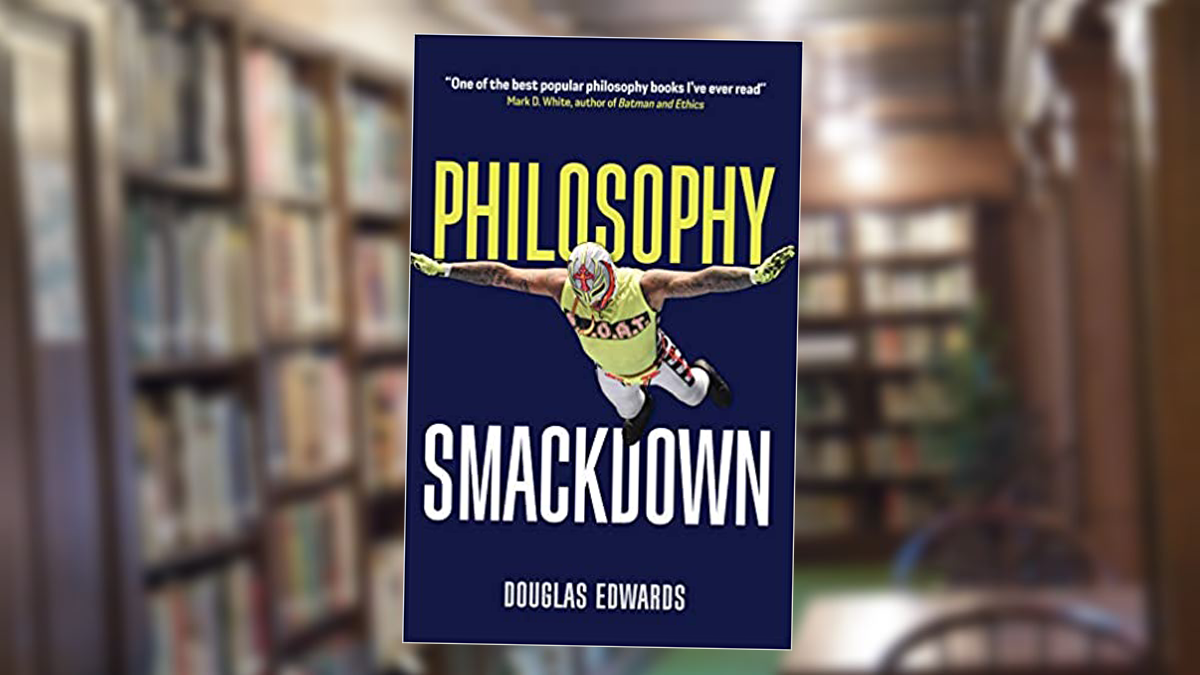

Pro wrestling and philosophy may seem like a mismatched tag team akin to WWE’s The Allied Powers team of Lex Luger and the late British Bulldog. But for Dr. Douglas Edwards, author of the book Philosophy Smackdown, out now from Polity, the two actually make a cohesive pair reminiscent of the Hart Foundation or the Brain Busters.

“I hope you’ll agree that pro wrestling is not only one of the most impressive and unique forms of entertainment around, but also that it can prompt us to think about some deep issues concerning who we are as human beings,” wrote the 37-year-old Edwards in the book’s “Preshow” introductory section. “And how we ought to relate to each other both individually and culturally. This is why I think pro wrestling is so apt for philosophical investigation: philosophy asks questions such as ‘What’s reality really like beneath the appearances?’, ‘What is it to be free?’, ‘What makes us the people we are?’, and ‘What is it to be a good person?’, which are all questions that arise when thinking about pro wrestling.”

Dr. Douglas Edwards.

In addition, Edwards brings up two key points in the book on why philosophy should resonate with pro wrestling fans, with the first being that “a lot of pro wrestling fans are already doing philosophy without even knowing it.”

We are?

“I think a lot of philosophy is about debate and discussion and disagreements, solving disagreements and arguing with each other,” revealed Edwards, who currently resides in Upstate New York and teaches at Utica College, in a phone interview with SlamWrestling.net. “Wrestling fans definitely do a fair bit of that! I think they’re doing philosophy because they’re engaging in critical discussion and engaging in issues like credibility and who should you trust. Who are the reliable sources? Especially now this is an incredibly difficult thing to do when you’ve got so many different podcasts, newsletters, websites, and social media accounts. You’re trying to work out what was the real story. Philosophical analysis is taking a lot of information and arguments and trying to work out what’s really going on.”

The second point Edwards brings forth is that “philosophy, in many respects, has a mainstream image problem just as significant – if not more so – than pro wrestling does, in that it is often marginalized and frequently misunderstood.”

I know this reader/pro wrestling fan can relate to that. I don’t know how many times I’ve told someone I’m a pro wrestling journalist only to be met with, “Is that a real thing?” Likewise, Edwards shared with me that, even though he’s been teaching and studying philosophy for most of his adult life, there are still friends and family members who don’t know what philosophy is despite his best efforts to enlighten them.

Edwards explained further that pro wrestling in a way “was always in a desperate effort to become accepted as part of the entertainment community, but (it) was never fully embraced.” In the same way philosophy, which Edwards reminded is mostly taught through higher education leaving a lot of people unexposed to the subject, is also often quickly dismissed as having this connotation of being “out of touch” and not something to be taken seriously as philosophers just “speculate wildly about nonsensical things.”

“They’re both (pro wrestling and philosophy) kind of like these things that are not really known about,” observed Edwards. “Most people will have a rough sense of what they might be, but it’s probably not going to be a very positive sense.”

He added, “This was almost kind of an accidental commonality. They should be more central, whether as forms of entertainment, forms of academic study or forms of ways of understanding important cultural things. But they’re (both) kind of pushed to the side for whatever reason.”

While this is not Edwards’ first book, it is his first book focusing on pro wrestling and philosophy. Although it must be noted he did slip in a Stone Cold Steve Austin reference into a previous book exploring the concept of truth. (I think that deserves a “Hell Yeah!”) Growing up in southeast England, Edwards says he first started watching pro wrestling at about the age of 10 or 11, when one of his younger brother’s friends brought over some WrestleMania VHS tapes. (For our younger readers, these were the days before DVDs, Blu-rays, the internet and streaming services!) Edwards says he was “immediately drawn to the colorful and heroic characters” and how watching pro wrestling was like seeing “action figures com(ing) to life.”

Edwards and his brother “would do exactly what they tell you not to do” by creating their own wrestling ring out of a duvet cover to grapple on in their bedrooms, fashioning homemade championship belts and other props and even using the ladder for the attic to have ladder matches. Fun fact: Edwards is also a Bret Hart fan which was not always well received especially when Hart and the British Bulldog faced each other at the 1992 SummerSlam hosted at Wembley Stadium in London.

So those Slam readers/pro wrestling fans not familiar with philosophy, take a deep breath and don’t be quick to count this book out. You are in relatable and capable hands here with Edwards. I think this would be the perfect time to acknowledge that Edwards was able to get a grant from his employer to attend both WrestleMania 35 and the Ring of Honor/New Japan G1 Supercard event as part of researching the book. “That was something that I think gave me something of a heroic status amongst my colleagues,” joked Edwards. He also listened to so many pro wrestling podcasts, including those featuring Conrad Thompson, that his young son started developing a slight, southern drawl. True story! I think that deserves a second, “Hell yeah!”

So, if this is your first time experiencing philosophy, consider yourself fortunate. I was introduced to philosophy in university and I would have gladly traded one of my precious packages of ramen noodles to take a philosophy of pro wrestling class. Instead, I was required to buy textbooks that were definitely not as accessible, welcoming nor as interesting as Edwards’ book. (Edwards is currently teaching a philosophy of sport class, where spoiler: his students will be reading a chapter of his book; he has not ruled out the debut of a philosophy of pro wrestling class in the future.)

Lucky for us readers, Edwards’ book has nothing in common with the philosophy textbooks I’ve previously encountered and quickly resold to my university book store after final exams. To begin with, he has broken the book into six approachable chapters: “Reality: Work vs Shoot,” “Freedom: Scripting vs Spontaneity,” “Identity: Person vs Gimmick,” “Morality: Babyface vs Heel,” “Justice: Prejudice vs Progress,” and “Meaning: Sport vs Monster.” Edwards also includes a bonus section called “Dark Match: Pro Wrestling vs Philosophy,” that much like the glossary at the beginning of the book for those unfamiliar with pro wrestling, will be useful to pro wrestling readers venturing into philosophy for the first time. It also reminded me of a scene in the movie, Road Trip, where one character helps another study for his philosophy final by comparing key terms/events in the subject to pro wrestling. If this is your first foray into philosophy, I don’t recommend reading the whole book in one sitting. That reading approach will most likely leave you feeling overwhelmed. Instead treat reading this book like a steak you just cooked on the grill: let it rest a bit and it will be much more enjoyable.

Edwards also utilizes plenty of subheadings throughout his prose to break down the philosophy into clearer and more digestible chunks. In each chapter, he also amply references incidents in pro wrestling that explore some of these important themes in philosophy. For example, in the aforementioned chapter on identity, which was a highlight for this reader, Edwards utilized the comings and goings of pro wrestler, Scott Hall. Pro wrestling fans will remember that Hall portrayed Razor Ramon in the WWE before he left for WCW where he used his real name.

Edwards questioned in the book, “What, then happens to the character of Razor Ramon: Does the character continue to exist? Is this the end of the character, as its portrayer is no longer around?” In retaliation the WWE “filed a lawsuit for copyright infringement” and had the wrestler, Rick Bognar, portray what fans have referred to as “Fake Razor” on their programming.

Edwards wrote later in the chapter: “This conflict shows an interesting feature of public entities. In a sense, the character Razor Ramon is an institutional entity: a copyrighted character, owned by a corporation. In these terms, there isn’t a question of where Razor Ramon is in October 1996: he is in the WWF, being portrayed by Rick Bognar. The WWF owns the character, and the rights to it, so wherever they say it is, it is. The lack of acceptance of this truth by fans and the wider wrestling community, though, suggests that this is not decisive: there can be an evolution of the nature of an entity that transcends its origin, and changes its nature from what it was originally intended to be. Whilst an institution has some control over the entities it creates, the broader public has a degree of control too over whether or not they accept the legitimacy of the institution and its creation.”

So I get it. I may have lost a few readers over the above discussion. Despite Edwards’ best efforts, a book combining pro wrestling and philosophy just isn’t going to appeal to all pro wrestling fans/readers. And that’s OK. But if you’re willing and/or looking to have your pro wrestling with some intellectual substance, this just might be the book for you!

“I really wanted the book to open as many doors, as many eyes as possible from all those different directions,” concluded Edwards, who hasn’t ruled out writing a follow-up book combining his passions for philosophy and pro wrestling. “The other thing I was hoping with the book is that in terms of both wrestling and philosophy is that people who read it who don’t know anything about philosophy get an appreciation for it. Or people who don’t know anything about wrestling gain an appreciation of wrestling. And people who’ve never come across either of them will come away thinking, ‘Oh, there’s a lot more to these things than I thought!’”

RELATED LINKS:

- Buy Philosophy Smackdown on Amazon.ca

- Buy Philosophy Smackdown on Amazon.com

- Philosophy Smackdown on Polity website

- Dr. Douglas Edwards: Book website and Twitter

- SlamWrestling Master Book List

MORE ACADEMIC WRESTLING READING:

- October 9, 2019: Lucha Libre Killer makes for captivating reading

- October 22, 2018: Writing about wrestling’s history definitely Tim Hornbaker’s ‘Territory’

- May 11, 2016: Book on prairie wrestling ‘substantive and enlightening’

- April 20, 2014: New book details pre-1900 pioneers of pro wrestling

- November 13, 2013: Quebec history book finally finds a French home

- September 29, 2010: Memphis Wrestling History Presents 1982 is one to add to the collection

- April 18, 2005: Essay book simply academic

- March 30, 2005: Almanac clarifies Quebec’s indy scene

- January 3, 2005: Author targets Minnesota’s wrestling legacy

- March 31, 2003: Buffalo book sales heat up

- September 16, 1999: Almanac explores rich Western heritage