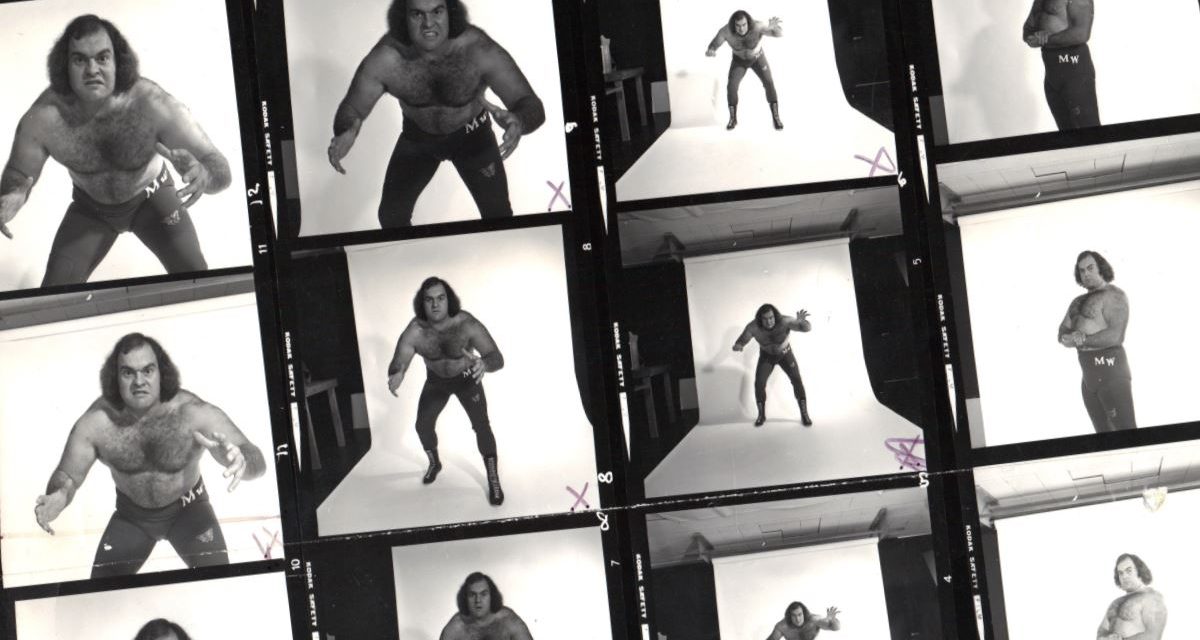

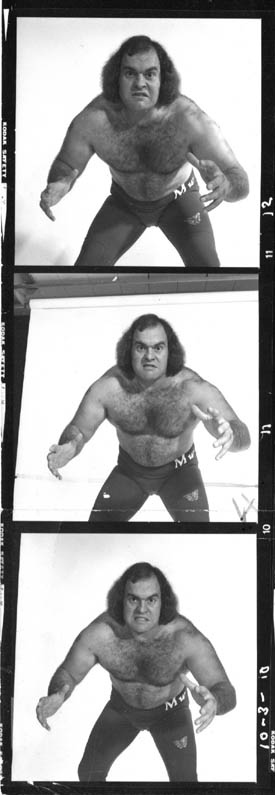

In his lifetime, Iron Mike Webster has enjoyed the distinction of being recognizable across Canada for three different pursuits: as Mike Webster, a Notre Dame gridiron collegian and Grey Cup-winning Canadian pro football lineman; then as Iron Mike, a hated tag team and heavyweight wrestling champion on syndicated national TV; and finally as Dr. Michael Webster, a renowned psychologist whose practice is built on working with police and security forces in negotiation strategy during hostage takings and hostile occupations.

His work has included training and advising the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Federal Bureau of Investigation, and Central and South America. More recently, Webster’s outspoken criticism of the RCMP’s corporate culture and reckless use of tasers in British Columbia has made him a much-quoted expert by civil libertarians and police reform advocates. In the first part of this profile, the focus is on Webster’s youth and football career.

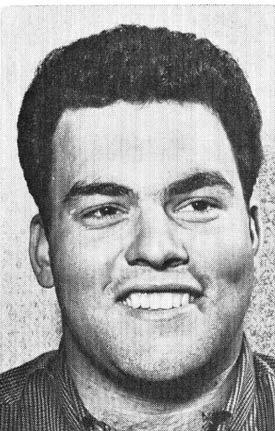

Mike Webster was born in Victoria, British Columbia, and raised in Vancouver. Although already 6 feet tall and 235 pounds at age 14, athletics did not come naturally.

“I was not very agile or coordinated, so there was no baseball, basketball or soccer,” Webster told SLAM! Wrestling. “Coach used me as an ‘enforcer’ in box lacrosse, I was always trying to fight or maim somebody. I discovered football and rugby in high school and felt like I had finally found my niche. I loved to hit people!”

In Grades 11 and 12 Webster, by now 6’2″ and 260 pounds, was invited to BC Lions’ Development Camp and the Lions’ coaches sent films to U.S. colleges. Webster had many offers from PAC 8, Big Sky, and Big 10 conference schools but one opportunity stood out.

“BC Lions’ offensive line coach ‘Blackie’ Johnson was a Notre Dame alumnus, he sold me on Notre Dame, and after visiting campus, I would go to no other school. Mom and Dad couldn’t afford Catholic education for me and my sister — so they pushed hard also.”

The legendary Notre Dame football program had been in decline for about a decade but in Webster’s senior year, that changed with the hiring of a new head coach, Ara Parseghian. The squad had won only two games in 1963, but under their new coach, the “Elephant Backfield” were all switched to playing the line. With Heisman Trophy winner John Huarte at quarterback tossing the ball to soon-to-be L.A. Rams end Jack Snow in a revamped offense, and future NFL star Alan Page dominating at defensive tackle, the Fighting Irish gave up only 68 yards on the ground per game while chalking up nine wins, including defeating future Super Bowl winners Roger Staubach at Navy and Bob Griese at Purdue.

“Playing at Notre Dame even in the lean years was overwhelming! Treated like royalty wherever we went — Americans love N.D., but being with Notre Dame on the rise (even as an alternate DT / short yardage — goal line type) was a mixed blessing,” explained Webster.

“I was over the moon because I was playing at such a prestigious school — but heartbroken because I wasn’t a starter. The biggest influence on me was the defensive backfield coach, Bill Daddio, who used to walk around with a pocket full of candies that he would hand out if he thought you needed one. He often caught me moping as a result of my alternate role — he taught me my limits as an athlete and the fact that it wasn’t about me, but the team. I had very little to do with Ara P. — the only players who knew him well were the 1st team backfield.”

“However, my interest in psychology had begun and I observed him closely — I was most taken with his intense style and his pre-game pep talks. From him I learned to keep it simple, relevant, and unpredictable — all things I took with me to wrestling.”

Not considered NFL material, Webster headed home to the Canadian Football League and after a brief stint with the Lions, moved east and wore #67 with some dreadful Montreal Alouettes teams in the late 1960s.

There was substantial societal turmoil in that era, both in Canada with regards to the rise of Quebec nationalism and in the U.S., torn by the struggle of the civil rights movement. Montreal was where Jackie Robinson was sent by the Brooklyn Dodgers to break into professional baseball in 1947, and as a cosmopolitan big city, being a black athlete was somewhat easier.

The Als had the only black starting quarterback in pro football in 1967/68 with Xavier University’s Carroll Williams, who is remembered as a pioneer of integration of sports in the South. (No slight intended to Marlin Briscoe, who took snaps for the AFL Denver Broncos in an emergency role in fall 1968.)

“Montreal had many black players in that era — including defensive end John Baker, halfbacks like Don Lisbon and two guys who went on to the NFL, Moses Denson and Dave Lewis,” recalled Webster. “Of course there were racial tensions, most often surfacing during the competition of training camp, but it was my impression that we all got along pretty well. I can recall a birthday party for my son where all of the players were in attendance — something not often seen on other teams.”

The 1970 Montreal team had only nine returning veterans and barely broke even in the won-loss column, but shocked the country by beating the Calgary Stampeders handily in the championship Grey Cup game 23-10. No one figured that QB Sonny Wade could overcome a Stamps team that had just taken the CFL equivalent of the Ice Bowl over Saskatchewan on the final play, to emerge from the West. But the intangibles, like character, took the Eastern reps to the podium. Among the team were Bob Storey, whose father “Red” was an iconic Grey Cup hero and NHL hockey ref and commentator, kicker George Springate, who was a cop turned Quebec provincial politician, and CFL Hall of Famers Terry Evanshan and Peter Dalla Riva at offensive ends and defensive halfbacks Larry Fairholm and Gene Gaines.

“That’s a lot of interesting characters on one roster right there, absolutely!” admitted Webster. “All interesting characters in addition to skilled athletes but I can’t resist a George Springate story. When he left the Montreal Police Department to run for the MNA position [in Pt. St. Charles] he needed a couple of bodyguards — hey presto! (Centre) Basil Bark and I survived the extremely rigorous hiring process and landed off-season jobs!”

In the long term, the most famous of all Webster’s teammates had arrived and departed before that Grey Cup season, Wayne Coleman in 1968. He is better known under his wrestling name, WWWF champ, Superstar Billy Graham.

“Wayne Coleman had all the physical potential in the world,” said Webster. “But, he did not enjoy hitting or being hit — he did not have the ‘killer’ instinct. On another note he was a scream to be with — he always had us laughing. One day he thought that squeezing his $500 African grey parrot would prompt it to speak to us.”

Mike Webster, football player.

One of the players Webster lined up against was the powerful Bob Lueck of Calgary, who convinced Coleman to come to Canada and later brought him to Calgary and introduced him to Stu Hart, for whom Lueck wrestled high on the cards in the off-season. And Angelo Mosca was, of course, a long-time two-sport star with Hamilton as well. But Webster hadn’t considered following them into the ring, until a chance meeting with “Canada’s Greatest Athlete,” former NWA kingpin Gene Kiniski, in the gym during the 1971 off season, and a fateful phone call.

No longer wanted by the Alouettes, Webster was heavy into powerlifting at the time and Kiniski took the now 320-pounder to meet promoter Sandor Kovacs. Trying to help Webster find a new team, Kiniski called his old Edmonton teammate, and new BC Lions coach and general manager, Eagle Keys.

“I was looking forward to a long career in football. I had no idea that my union involvement would influence people’s decisions about me — although I had always been a wrestling fan (due to ‘Big Daddy’ Gene Lipscomb, Wahoo McDaniel, et al). I was studying at McGill, during my time in Montreal, and was looking forward to psychology after football. When Gene told me what Coach Keyes had said, I could see the writing on the wall. The Hamilton GM, Ralph Sazio, traded for me and invited me to camp, with a significant cut in my salary.” (Webster would be walking into a starting spot, replacing just-retired DT John Barrow, on the Ti-Cats beside Mosca).

“I talked to Gene who convinced me I could make more money with him — he was right and I never looked back!”

RELATED LINKS

The evolution of Mike Webster: Psychologist … and head of the RCMP?

Coming from a family of Winnipeg Blue Bomber fans, the first set of sports cards Marty Goldstein collected was the 1968 CFL set. Mike Webster was one of the first he got. Marty specializes in old-school sports retrospectives and interviews, and has relaunched The Great Canadian Talk Show as a Podcast.