Whenever the Hart name is brought up in pro wrestling circles, attention is immediately focused on Stu Hart’s brood in Western Canada but the careers of a transplanted Hollander named Frankie Hart and his son Bobby Hart deserve equal scrutiny.

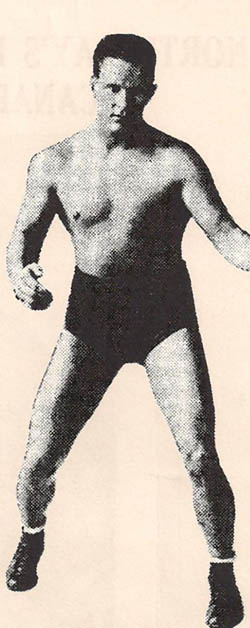

Frankie Hart.

At about the same time that Stu Hart was carving out a career and fathering a stable of future wrestling stars, Frankie Hart quietly went about establishing a respected reputation in the ring and raising a large family in Northern Ontario. Whereas most of Stu’s sons took to the mat as naturally as oil flows in the Calgary fields only one of Frankie’s sons followed him into the squared circle when Bobby pursued a career. Another son Dave married the daughter of wrestler Benny Trudel. The two Hart families were not related.

Franciscus Johannes Hart was born in Groningen, Holland in 1909 and learned Greco-Roman wrestling while serving a term in the Dutch cavalry. He developed a sound skill in gymnastics and later immigrated to Canada where he settled in Toronto.

Frankie wasted little time in mapping out his future when he met and married Delma Peloquin. Career paths opened when he fell in with a young Polish wrestler from Renfrew, Ontario named Alex Kasaboski. Hart worked out with Kasaboski and a few other wrestlers in a Toronto gym and soon started wrestling competitively throughout Ontario.

The Harts later moved to the Windsor area, where Frankie worked at the Ford Motor Company during the day and made a few extra dollars wrestling in the evening. But it soon became apparent that the young Dutchman was somewhat more adept between the ropes than he was at learning the ropes on an assembly line.

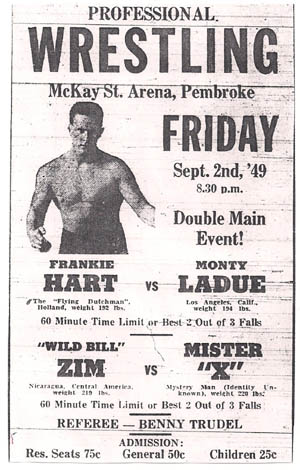

Like most mat men of the period, Hart worked in all the North American territories from the 1930s through the 1950s and quickly became a fan favorite wherever he appeared. He became known as the Flying Dutchman with his lightning fast moves and high flying tactics. Never more than 200 pounds, Hart’s style was described as cool, scientific, fast and acrobatic. His finishing hold was the Flying Dutch Windmill, a combination of leg scissors and body slams. Early contemporaries were Jackie Nichols, Monte La Due, Rene Labelle and Wild Bill Zim as well as both Larry and Alex Kasaboski, Herb Parks and Benny Trudel.

As smart as he was in the ring, he also had an eye on the future when his ring days were over. With that in mind he purchased a parcel of land in Northern Ontario on Lake Washagami just below the rich nickel city of Sudbury. Hart built a tourist resort called Pine Falls Lodge where he and his wife would raise their five sons and one daughter. Frankie still worked in all the American promotions while wife Delma home schooled the children. He returned home at Christmas and Easter and during the summer. In between, he checked in regularly with the family from Texas, California, the Pacific Northwest, Columbus, Detroit and Chicago.

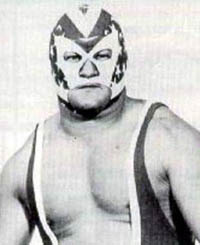

Bobby Hart and Lorenzo Parente.

At about the same time Hart was establishing his tourist resort, another veteran wrestler named Herb Parks was doing the same thing in North Bay, Ontario. The two tourist businesses would blend in nicely with Larry Kasaboski’s fledgling Northland Wrestling promotion.

North Bay wrestling legend Bill Curry was starting out in the game in the early 1950s when Frankie was in the twilight of his career. They both worked for Kasaboski.

“He was a good gymnast,” Bill recalled, “and had been around for awhile before I met him. He was a classy wrestler with some good moves. Larry and I would often go moose hunting at Frankie’s lodge at Washagami. I got to know all his family.”

Many wrestlers would pass through Pine Falls and it gave the Hart family the opportunity to meet pros such as Dale Wayne, Morris Shapiro (The Mighty Atlas), Herb and Dinty Parks, Don Evans and Dutch Schultz. The Hart boys gravitated to the wrestlers and perhaps it was a foregone conclusion that at least one of the five boys would follow in the footsteps of their father. It wasn’t long before it became apparent that father Frankie would pass the torch to Bobby Hart.

This Hart family didn’t learn the hard knocks of the game in a dungeon but rather on the living room rug of the Lodge.

Bobby Hart.

“Dad would get down on the rug in the living room and wrestle with all us boys,” Harry Hart remembered. “Bobby was 10 years old when he knew he wanted to become a wrestler. Dad would encourage him. As Bobby grew, he never lost the desire to wrestle and it only became a matter of time before he would take it up seriously.”

One by one the Hart boys left the lodge to strike out on their own and it wasn’t long before Bobby was out of high school and working for the railroad in North Bay. But he remained close to the game and in his early twenties was ready to begin a full time career. With personal attention devoted to bodybuilding and instruction from his father and wrestlers such as Curry, Bobby was ready to turn pro.

His first bout ended in a draw against Jim Siskay and from that point the younger Hart never looked back.

“I trained Bobby for about a year when he was in his late teens attending Scollard Hall in North Bay,” Bill Curry recalled. “He worked for the railway after that and then went full-time for Larry. He caught a good break when he went to Charlotte, North Carolina. He went on a tour of Japan and got a good payday in American dollars. I believe he did a few tours after that.”

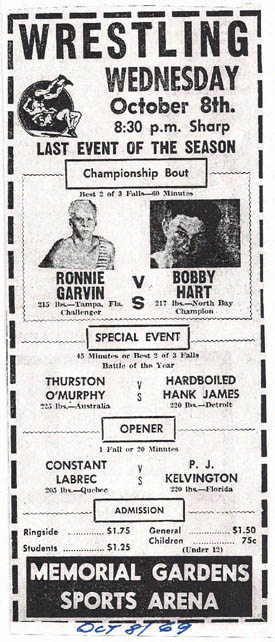

Bobby’s career would parallel his father’s in that he worked for the Kasaboski promotion in the summer months and then headed for the American circuits when Larry closed up shop for the season. It was while making a name in the north, he met another up-and-comer named Ronnie Garvin and the two, along with Terry Garvin would carry the promotion for several years in the 1960s.

Ronnie Garvin remembers well his early days in Northern Ontario working for Kasaboski. Not that the money was that great but more out of a sense of loyalty and friendship towards Kasaboski, the Garvins returned yearly throughout the 1960s to help keep the promotion alive. Ronnie wore the North American Jr. Heavyweight belt as the local champion and defended it against all comers including Hart.

“I knew Bobby and his father and often went up to Washagami to hunt. Bobby was a worthy opponent and later when I turned face, I teamed with him on occasion. We also worked in Frankie on a few gimmicks,” said Garvin.

One of the better storytellers in the game, Ronnie recalled an incident he and Bobby were involved in that was both serious and amusing.

“We were coming from Rouyn-Noranda and Bobby was driving. Suddenly we came face to face with an old pick-up truck. The truck was on the same side of the road and just missed us by inches, almost putting us in the ditch. Bobby turned around and gave chase. When he caught up with the guy, Bobby pulled alongside and yelled at him to pull over. When the truck stopped, Bobby got out of the car and approached the driver.”

The driver was a 50-year-old man and got the surprise of his life when Hart yanked him out of the truck, grabbed him by the collar and hair, spun him around and kicked him in the ass.

“Bobby took the keys from him and threw them as far away as he could from the old guy,” Ronnie continued. “‘You old son-of-a-bitch,’ Bobby shouted. ‘I’m going to save your life and somebody else’s too.'”

Eventually Ronnie Garvin left the territory for good, gradually carving out an illustrious career in the business. Bobby Hart also became a force to be reckoned with throughout the mat world.

But Hart’s fame would be achieved with a tag team partner named Lorenzo Parente and they would do so under masks as Dante (Hart) and Mephisto (Parente) throughout the 1960s. As the Continental Warriors, managed by Saul Weingeroff they were a very successful tag team.

Hart and Parente, with and without the masks, held numerous tag team titles throughout Alabama, Tennessee, and the Western States. The pair held the AWA Mid-American Tag Team belts on three occasions and the NWA (Alabama/Tennessee) World Tag Team Championship four times. In singles competition, Hart also held various titles in both the States and in Australia. Opponents on Hart’s resume included Len Rossi, Jerry Lawler, Jackie Fargo, Johnny Walker and Louie Tillet.

As he wound down his career in the 1970s, Bobby once again donned the mask, this time working as The Patriot with Percival A. Friend as his manager. The pair hooked up in Amarillo and became fast friends during their time in the territory. Al Friend remembers their days on the road and Bobby’s penchant for pulling ribs.

“Bobby had to have been one of the funniest guys to ever work with,” Friend recalled recently. “He was an excellent driver and great pilot as well. We would alternate cars on the road every week and give each other a break in the driving on all those long trips in the Amarillo territory. Bobby was a great family man and couldn’t wait to get back to Amarillo to see them. One of the funniest things he ever did was to wear a ball cap that said ‘Tennessee’ on it and go into a gas station and ask where Boise, Idaho was, all the while crossing his eyes as he looked at the clerk. I could hardly hold my laughter back.”

Frankie Hart.

Friend recalled that Hart had a good variety of wrestling holds and counter holds that had been learned from his father, Frankie, who he spoke a lot about on the trips.

“One of the best ribs he pulled on me,” Friend continued, “was on a Saturday evening trip back to Amarillo. We had parked across the street from a Circle K carry out on the old US 66 and went in to get some sandwiches and pop (with foam on it) and crossing back across the road, he hollered, ‘Snake!!!.’ I threw my foot-long hot dog with all the trimmings and my drink in the air and jumped nearly six feet in the opposite direction. Bobby just stood there with a smile on his face and began to laugh at me. I had to end up going back in and getting another order to go. Every few miles Bobby would just look over at me and start laughing and then I would laugh too. I left him in Amarillo in 1973 and returned to Ohio and went back to work for The Sheik. I miss Bobby a lot … he was one of the good guys in the business that I had the pleasure of traveling with.”

Even though he had a successful career that took him to Puerto Rico, Japan and Australia as well as all over North America, Hart never severed ties to Northern Ontario and when his ring days were over he returned to live in Sturgeon Falls with his wife and son. Bobby purchased several trucks and went into the logging business, hiring his brother Harry to work for him. The brothers were always close even from their childhood days at the lodge.

“Even when we were little shavers, we were always paired for the work that had to be done. After we left the lodge and got out on our own, we still did things together … skiing, fishing and motorcycling. He always had some plan to do interesting stuff, so he was my best buddy. Once he started wrestling and got married, I didn’t see too much of him because he began traveling in the States.”

When his father Frankie died in 1982, Bobby purchased the lodge and ran it successfully for many years. It was only natural that their bond would extend from the wrestling business to the tourist business, since father and son took pride in their endeavors and in the Hart name.

“I can still see him one time tearing into the lodge on a snowmobile wearing his Patriot mask, covered with the stars and stripes,” Harry chuckles. “Bobby always enjoyed a good laugh or a prank.”

Bobby Hart as The Patriot.

In 2001 at the age of 63, Bobby succumbed to cancer at the Sudbury Regional Hospital. No one mourned his passing more than his brother Harry.

“Bob and I often reminisced about all the things we did, some goofy, some serious but always fun when we spent time together,” Harry reflected. “Like my dad he was a natural storyteller and he could really hold an audience when talking about the gags the wrestlers pulled on each other. Another thing about Bob was that he was no complainer. When he got his bone marrow cancer he accepted it and carried on with whatever had to be done until it got to the point that he was no longer able to do it on his own. He went through a bad time before he died but never a word of complaint or regret did we hear.”

The young man who had once wrestled with his dad on the living room rug of their lodge on Lake Washagami had made his mark in the wrestling world under the Hart banner and was now ready to join his mentor in a bigger arena.

It was only fitting that father and son were reunited once again just as they had shared a special bond in the ring.

Note of thanks: Credit for the Frankie Hart material goes to Dave Hart. Credit for the Bobby Hart material goes to Harry Hart.