For wrestling fans in the lower Great Lakes during the 1970s, one TV memory lingers even with the passage of time — the thundering trumpets of Classical Gas in the background as the authoritative voice of Jack Reynolds introduced the weekly TV show.

Reynolds was many things during a radio and TV career that lasted almost half-a-century and landed him in the Ohio broadcasting hall of fame — nighttime disc jockey, bit actor, commercial pitchman, and TV movie host.

But few things endeared him to audiences as his call of the ring work of Johnny Powers, “Bulldog” Brower, Ernie Ladd, and Waldo von Erich, and Hulk Hogan.

“He was iconic,” said Powers, part-owner of the National Wrestling Federation and the biggest star in the promotion that ran in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York from the late 1960s until 1974. “His tenure spread across a large territory for many, many years and he just connected with the fans.”

Reynolds, real name Joseph J. Rizzo, died October 16, 2008, in a Cleveland area hospital, less than a month after undergoing heart bypass surgery that resulted in complications. He was 71.

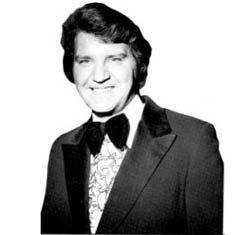

Jack Reynolds. Courtesy Carroll Hall

With him passes an era in which the host of the local territorial TV wrestling show also was also an important community figure, whose presence validated the sport and lent it an air of credibility.

According to Powers, who stayed in touch with him, Reynolds’ appeal was visceral, markedly different from the classic style of a Gordon Solie, who broke down holds and explained the intricacies of matches for viewers. In a more circumspect time, Reynolds liked the good guys and couldn’t believe what the bad guys got away with.

“It was one of those situations where it didn’t matter that he couldn’t tell a top wristlock from a hammerlock,” Powers said. “What made him special in the fans’ eyes was that he was a believer. Even when he walked in the dressing room, he suspended judgment. The fans knew that he liked the athletes and respected the business.”

Reynolds got his start in broadcasting in 1961, when he was working as a barber, earning a part-time gig on a jazz show at WCUY-FM.

“My mother’s beauty salon sponsored the second hour of the show, and I worked for $1.50 an hour. But I would have worked for nothing. I just wanted to get into radio,” he told the [Elyria] Chronicle-Telegram in 1984. A Cleveland native, he changed his on-air name to Reynolds since ethnic names like Rizzo were considered off-putting at the time.

He kept up with his tonsorial license for several years, but his full, rich voice launched him into a top slot in local broadcasting. He joined WHK-AM, hosting an all-night show, and stepped in front of the camera when Powers and Pedro Martinez revived the dormant Cleveland promotion in 1969. The TV tapings for the NWF were held at WUAB-TV, an independent station in Parma, Ohio, where Reynolds also worked for years as a staff announcer.

“One day, our operations manager asked if I knew anything about professional wrestling,” Reynolds said. “I said, ‘Yeah, I used to be a big fan.'” Thus was born Championship Wrestling, which aired in a wide swath from northeastern Ohio to upstate New York markets like Syracuse and Utica for the next five years.

His best known radio work came in the 1970s and 1980s at WWWE-AM in Cleveland, the most powerful station in the market and the home of Cleveland sports. For years, he hosted an overnight show from midnight to 5:30 a.m. that touched on all kinds of music, banter, and sports.

“He seems to enjoy doing the all-night show, chatting animatedly with his callers on and off the air,” Cleveland area TV writer Ken Gottlieb once observed. “This is an ideal arrangement,” Reynolds said of his job. “I have as much freedom as anyone at the station. I’ve never been a 9-to-5 person. I hate it.”

That’s where wrestling stepped in, as “Beautiful” Bruce Swayze, a veteran worker for the NWF, reflected. To round out time while entertaining insomniacs and third-shift workers, Reynolds routinely called Swayze late at night with a simple plea.

“I’d come into town, I’d get in bed and the phone would ring. He’d say, ‘Where are you?’ I’d say, ‘I’m in bed.’ He’d say, ‘Sit on the side of the bed and call me back in one minute,'” Swayze said. “He’d have me on the radio with him and we’d talk for an hour. We told road stories and had a lot of fun.”

If Reynolds was affable with fans and got along with most everyone, there was one exception — The Sheik. “Pedro wanted me to come to the old Cleveland Arena on a Thursday night and announce the main event between The Sheik and Johnny Powers,” Reynolds once told SLAM! Wrestling. “I go over there and he put up a fuss. ‘Why is he here? I want my own ring announcer!'”

Reynolds said he was ready to leave, but Martinez he insisted he stay. He said, ‘You’re the one I want and I want you to run the card next week.’ I said, ‘OK.’ But [The Sheik] was a miserable, backstabbing, conniving person.”

One of his favorite memories was the “Super Bowl of Wrestling,” a three-ring extravaganza held at Cleveland Municipal Stadium in August 1972, when Powers and Johnny Valentine squared off in what Reynolds described as a “a classic match.”

Reynolds played a role in the build-up to the main event. He was at WHK-AM at the time, and was asked to broadcast a Friday night match in Cleveland between Valentine and Powers. The match never took place as Valentine attacked Powers before the bell rang and beat him to a bloody pulp, breaking his nose and setting up the big card.

As Swayze recalled, Reynolds wasn’t privy to the backstage wheelings and dealings, mapping out talking points for the matches. That made his reaction to the in-ring action authentic, and that’s what viewers saw.

“He took a poke at me,” said Swayze, who was managing Abdullah the Butcher during an angle with Powers. “We kicked the living bejeezus out of him at the TV station. Reynolds got so upset — he was half a mark — that he took a poke at me.

“He was shooting. He took a real serious shot at me, honest to God. He came right out of the announcing chair,” Swayze said with a warm chuckle. “God bless him. What a wonderful guy.”

When the NWF shut down, Reynolds stepped in as play-by-play announcer for Martinez’s next endeavor, the International Wrestling Association, in 1975. You can still hear him calling matches with Tex McKenzie when IWA tapes pop up on ESPN shows like Cheap Seats.

“He was a prince of a guy. Hadn’t heard from him in almost 30 years but I still counted him as a friend,” said Ron Martinez, Pedro’s son, who was Reynolds’ partner on NWF broadcasts. And Rick Gattone, son of the legendary Baron Gattoni and a ring announcer for the IWA, added: “I knew Jack and remember him to always be positive, helpful, and creative. In his role as color commentator and interviewer, Mr. Reynolds was unsurpassed.”

Reynolds played a prominent role in the days just after the WWF went national in 1984. He teamed with Angelo Mosca and later Jesse Ventura on All-Star Wrestling and was the lead man for Prime Time Wrestling on USA when it debuted in 1985.

Back home at WUAB, Reynolds hosted a movie show, a one-time favorite of local programmers that’s since faded into oblivion. He called baseball, horse racing, and other sports, and got a role as an extra in The Godfather, thanks to a helping hand from a former colleague. Reynolds played an army officer.

He stayed involved in wrestling for years, working as an announcer and handler on overseas trips for several promoters through 2001 to places like India and the Philippines. In recent years, he worked with sports handicapper Marc Lawrence on a nationally syndicated radio show analyzing pro football matchups.

In 2001, Reynolds was inducted into the Radio/Television Broadcaster’s Hall of Fame of Ohio. His son Tony is the sports anchor at the Fox affiliate in Cleveland and also hosts a daily radio show on which his dad sometimes appeared.

“Jack was a wonderful man, warm, funny, and a tremendous storyteller. He had a million tales about the wrestling, baseball, and football worlds,” handicapper and researcher Kevin O’Neill, a regular guest on the sports handicapping show, wrote upon Reynolds’ death.

The WWE Web site posted a note of condolences to Reynolds and his family. He is survived by Carol Jean, his wife of 50 years, and three children. A funeral will be held Oct. 20 at St. Bartholomew Catholic Church in Middleburg Heights, Ohio.