In Crystal Beach, Ontario, along the shores of Lake Erie, Fred Atkins’ finishing school nearly finished off more than a few aspiring wrestlers.

But the collection of names that went through his training routine — Tiger Jeet Singh, Adrian Adonis, Sailor Art Thomas, Giant Baba, Professor Hiro — is a testament to the fact that only the strong survive.

Atkins, who died May 14, 1988, wouldn’t have wanted it any other way.

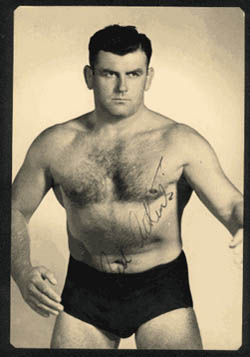

Fred Atkins

By the time the 1960s rolled around, Atkins didn’t have much interest in wrestling any longer, but he did continue to fight on occasion and referee (s-l-o-w-l-y) for some time thereafter.

Instead, he turned his attention to training, which had been a fascination his whole life.

Born in 1910 in Westport, New Zealand, Atkins found work as a young man cutting railway ties in the Australian outback. After work, he would wrestle in town for exercise and fun. Only later would he realize there was decent money to be made as a professional wrestler.

“I wrestled in the amateur ranks for five years before I turned pro during the war,” Atkins is quoted as saying in a magazine. “[I]t taught me the advantage of strength mixed with science. Maybe a 250-pound giant with a little wrestling skill might beat a 175-pound scientific wrestler by grinding him into the ground. But no 250-pound giant will ever beat a scientific wrestler of anywhere near his weight — not without a lot of luck or a brother-in-law for a referee!”

Atkins looked the part, a 6-foot-1 man “whose chin looks as though carved out of granite and whose eyes seem to look right through you.”

In Australia, the championship-caliber Atkins met touring North American wrestlers such as Strangler Lewis, Doc Len Hall and John Katan. It was Lewis that arranged a six-month tour for Atkins with San Francisco promoter Joe Malcewicz, but Atkins returned after his visa expired. John Katan, who promoted Hamilton, Ontario, talked to Toronto major domo Frank Tunney about bringing Atkins in. The rest, they say, is history.

In 1949, Atkins upset Whipper Billy Watson for the British Empire title when nobody thought it could be done. The Whip considered Atkins among the 10 best in the world at the time. “You’d never see Fred do a dropkick, never a flying tackle. That was not his style. His was a Greco-Roman style, closer to Olympic-type wrestling than anybody else.”

A young Fred Atkins. Courtesy www.mapleleafwrestling.com

His reputation as a brute was evident. “There are two schools of thought about Atkins — one contends he is solid oak, the other, granite,” wrote the Kingston Whig Standard in 1954.

In a magazine piece, an anonymous opponent opines (whines?) about Atkins: “He makes you afraid of him. I can’t say I fear many wrestlers, but this guy is so rough you almost know you’re going to get hurt. It’s not that he’s cruel or sadistic, like some others I could name, but Fred is just so darn rough you ache even before you climb in there with him!”

In 2002, the late Kinji Shibuya remembered Atkins as a “great beer drinker!” They teamed on one occasion against former boxing champ Primo Carnera. “You know how big he was, size 22 shoe or something like that. He wrestled Moto and knocked all his teeth out! So when he got in the ring there with me, I said, ‘Let me get my ass out of here before he knocks my teeth out!'” laughed Shibuya. “Atkins, he’d go there and get Primo Carnera yelling.”

While most of his true peers are gone, like championship tag team partners Gene Kiniski, Lord Athol Layton and Rey Eckert, Atkins stayed involved for years to come, working his final match in 1971, and inspiring stories.

“Man, that Fred Atkins, he was something else,” recalled Charlie Fulton. “He was a tough guy. I’ve seen him put a couple of guys in their place; they were kind of mouthy, trying to act like big shots and stuff. I don’t think he was afraid of anybody. He was an old man when I met him.”

“I remember my first match was with Fred Atkins. He almost killed me,” said Frank Martinez in an interview with Scott Teal’s Whatever Happened To … ? newsletter. “Fred Atkins was an old man then, but he was strong. He knocked me, from corner to corner, with no mercy.”

No mercy described his training style too.

Atkins had settled in Crystal Beach in a modest bungalow, away from the big city, with his wife “Teddy” Edna Mae and daughter Robyn. Well-known around town, when promoters sent him wrestlers they would be billeted with locals. Tiger Jeet Singh, for example, stayed in a garage across from the Atkins’ home.

At 6 a.m., Atkins would be knocking on the door to get Singh up. “He’d wake me up early in the morning, take me to the beach and make me run in the sand with the heavy shoes. This is how he got me training.”

“I loved Atkins. He told it as it was,” said Duncan McTavish. “The minute his feet hit the beach, he was running. They brought that Professor Hiro over, and he must have blown about 60 pounds working with Fred.”

The likes of Baba and Singh were paid to train with Atkins by their sponsoring promoters. The local boys would pay $25 a day for the chance to workout with Atkins and learn some new, punishing moves.

“He had a mat in his basement, a horsehair mat and that was it, a mat on the concrete floor,” recalled Shillelagh O’Sullivan (Patrick McMahon). “Amateurish stuff, it was real wrestling that we learned from Fred, you know what I mean? It wasn’t the acrobatic stuff, it was the real stuff. It cost us when we started to wrestle because we were doing the real shoot wrestling. We were doing that and the other guys were surprised, and they didn’t want to work with us because we were too rough with them.”

Tiger Jeet concurred. He said Atkins never smartened him up to the inner workings of pro wrestling, just sending him into the Toronto ring with the goal to win, the opponent be damned.

“He was pretty tough. He was from the old school,” said Pat “Moose” Scott. “He was a tough customer. He trained us more or less the way these UFC guys are training now, except for the punching. He was heavily into the wrestling, Greco-Roman and that kind of thing. It was tough training with him, I’ll tell you that. There were a lot of guys who came there who didn’t stick around.”

Fred Atkins and Lee Henning from the Parkhurst wrestling card set of 1955.

Bernie Livingston had spent a couple of weeks with Whipper Watson on his farm polishing his skills, and went to Atkins to learn more on weekends. They learned how to “put holds on that nobody’s ever going to get out of, simple holds, how to take you down, very simple, how to put a hold on that nobody can get out of — and you didn’t have to be Superman to do it. Although he was a very strong man; at that time, he was getting up in age too — he’s older than me. He was a very good, no-nonsense wrestler.”

While most seem to have stories about Atkins’ toughness, they are coupled with his softer side, too.

“When you’re in his house, you’re treated like a guest in his house, and you’re treated like a king,” said Livingston. Singh, who lasted five years training with Atkins, said that Atkins’ wife said that her husband considered him like the son he never had.

“He’s — well, he’s just great. Loving, kind and as gentle as a kitten,” Edna is quoted as saying in a magazine piece. “He treats Robyn and me as though we were being held for a king’s ransom. And when that hard, craggy face of his lights up in a smile, it’s better than any sunset down in Queensland. I’ve never seen him wrestle, you know, although I’ve heard about how fierce and mean he is in the ring. Well, I just don’t believe it! Nobody as sweet as Fred could be like that.”

Singh said that Atkins preached stamina and pulling weights instead of lifting.

“He said, ‘Stamina is the most important thing in wrestling. If you have stamina, even if you don’t wrestle that great, but you can take over if somebody tries to get smart. If you blow up, then the other guy is going to take over.’ Stamina was his main key. He pushed me just to get in shape and train properly,” Singh said. “We’d pull the ropes; he always believed in pulling, never lifting weights. He’d have a pulley on one side of the weights, and he’d ask, ‘Just pull the ropes.’ That’s what his training was. That way you never get really big, but you get toned up. That’s what he believed in.”

Abe Zvonkin and Fred Atkins leave the ring. Terry Dart Colletion

Atkins’ fame as a trainer extended beyond wrestling. Local athletes sought him and, and then, in 1970, the NHL’s Buffalo Sabres came calling across the border.

“Atkins had been introduced to the yearling Sabres midway through their first season, after [general manager] Punch Imlach had seen his roster crammed with drinkers, smokers, hasbeens, and never-will-bes drop too many games just on conditioning alone,” reads Paul Wieland’s story in Then Perreault Said to Rico: The Best Buffalo Sabres Stories Ever Told. Training camps were more bonding sessions than real workouts, and in-season exercising wasn’t hardly the necessity it is now. “They did all these kinds of things in Buffalo’s camp until Fred Atkins showed up on the heels of a home loss in which the Sabres were so hung over and lackadaisical that Imlach couldn’t talk about his players without an every-other-word obscenity.”

Atkins shared his secret of training hockey players with the Toronto Sun in 1983, when he was working with the Toronto Maple Leafs at training camp. “A hockey player is the same as any other athlete. The trouble with them is, they’ve never been in shape. They’ve concentrated on building muscles, you see, when in athletics you have to be quick — and you lose quickness by lifting weights. I turn them around, get ’em stretching ligaments.”

And even in his old age, refereeing in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Atkins was still a tough, no-nonsense son of a bitch. He’s the third man in the ring when Harley Race beat Terry Funk for the NWA World title at Maple Leaf Gardens in 1977, for example.

Fans from the era have fond memories of the slow-moving, slow-counting Atkins in the referee shirt. He did keep law and order, perhaps better than anyone else, said Duncan McTavish. “I was working with Bobby Bass. He had a hold on me. Fred told him to break it, and Bobby said, ‘Go away, old man.’ When he said old man I shuddered. He picked Bobby up — and me — and threw us across the ring. He was tough!”